The Cut and Misunderstanding

Alejandro Olivos

In this article, I would like to present some thoughts that guide my clinical practice with autistic children at institutions like the IME (Institute Médico Educatif) in Paris. One of my duties as a clinical psychologist is to receive family members of the children admitted to the institution through a procedure known as the “family interview.” Although properly speaking, it cannot be called an analytic procedure, my work with these parents was inspired by the teachings of Jacques Lacan. The following remarks will provide a precise technique for conducting these interviews and listening to the discourse of the parents. This technique will operate utilizing elements on which the cut of the analytic session is based.

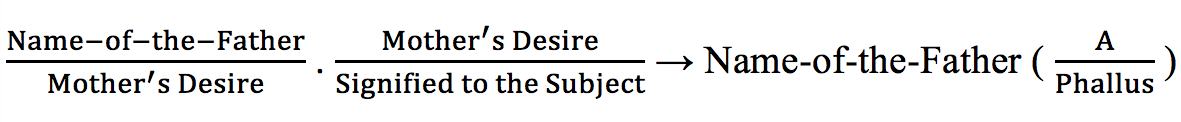

The nucleus of a traditional family consists of two parents and a child: dad, mom and their child. If we add this condition that the parents should not be of the same sex, the configuration becomes that of a “normal” family as sanctioned by traditional morality. However, all this has nothing to do with the psychoanalytic conception of the family. Lacan, from the start of his teaching career spoke of the father as the Name-of-the-Father, uncoupling this notion of the “daddy” from everyday life. For Lacan, it is a question of nomination: the father is someone whom one names as such, it is a question of declaration–– on the side of the mother–– and that which cannot be reduced to the imaginary dimension of someone’s demeanor, to the actual figure of someone, one calls “dad.” As a result, we cannot deduce a subjective function from someone’s physical behavior. The fact that a man might be a “good dad” in life does not at all mean that this man can occupy the paternal position, in relation to the child and also in relation to the mother. The paternal function cannot be verified except from its discourse as such, from what it says and from the place that each subject occupies in this discourse. Lacan thus introduces the question of the father on the basis of a function, a nominating function which in effect is a particular trait of the symbolic. And this is also how it distinguishes itself from the question of the mother because Lacan does not speak of a “Name-of-the-Mother” but of “Desire of the Mother,” –––already a major distinction. Thus for Lacan, the paternal metaphor can be written as:

(“On a Question Prior” 465)

Consequently, the mother and the father are not put on the same level, there is no equivalence between the two. We do not say “the Name-of-the-Father and the Name-of-the-Mother” but rather “the-Name-of-the-Father” and “the-Desire-of-the-Mother.” This means that the two terms or rather the two signifiers, are heterogeneous. The question that arises is the following: despite this radical difference is there any relation between the two terms? Here is the crucial point: the question of the child situates itself exactly “between” the father and the mother.

This follows from Jacques Borie’s remarkable talk in Valence for whom, in order for the child to locate itself within life [existence] it must situate itself within the fissure, the break, the gap between the father and the mother, within the “not-same” [pas-pareil] (Borie). The child tries to locate itself in the “not-same” of the father and the mother, who are nevertheless in a relation, the enigma of which poses itself as the enigma of procreation: “Where do children come from? What role did daddy play in this entire story?” It’s a mystery, and for Freud it is at the origin of the theories of infantile sexuality. However, when for diverse reasons one cannot speak of a “not-same,” when the break within the father and the mother is not certain, the family constitutes itself like the superego, like a commandment:

If the father and the mother are not in equivalence, that is to say, if there is a heterogeneity between the two, they are not on the same plane. Note for instance the difference with Melanie Klein, who is very interested in the parental couple herself but always operates under the well-known formula of “daddy-mommy.” This “daddy-mommy” is an ensemble, it produces a holophrase, father and mother coupled into one another, while Lacan does the exact opposite, he decouples them and shows their heterogeneous dimension […] The question of the child thus poses itself between the father and the mother and not in front of “daddy-mommy.” And this is why Lacan, when he comments on Melanie Klein’s “daddy-mommy” couple, points out that an expression like this constitutes the family as the superego, that is to say, as a commandment. The heterogeneity of man and woman, of father and mother is reduced, assembled, gelled into something else. As a result, the child cannot situate itself between the two but it is coupled to the imperative of the Other reduced to the One.

(Borie)

Note that the terms “father” and “mother,” are signifying elements. Here the father is put as a function, a function of nomination, and not as a “daddy,” that is “father of the family.” The heterogeneity in question, that of the man and the woman does not, in any way constitute an apologia for the parental heterosexual couple and the traditional family. As Sophie Marret-Maleval has pertinently observed, “Lacan runs counter to a platonic vision of love conceived as a reunion of lost halves, which makes the Other sex the complement to the first one in a perfect fusion” (Marret-Maleval).

In my analytic practice with autistic children, I have often–– but obviously, not always–– been confronted with a similar familial configuration in which the family constitutes itself as superego, like a command. The question that the parents ask of the institution–– such as mine own, during the “family interview,” when I am working with their child–– presents itself in some ways as being homogenized around a demand, a wish, that their child should speak. The only demand unanimously emerging out of these first parental interviews and addressed to us as an institution is this: “We want him to speak, that’s all.” It is quite shocking to listen to the parents speak, especially in some cases where the child does not show any behavioral problems, that although everything is fine, things will be even better if only child would speak up. From then on for the child the demand of the Other expresses itself in the form of an imperative, of an ultimate command: “Speak!” which is, we might observe, also the imperative of educative methods: “Communicate!”

The question that arises thus is the following: how to intervene in such situations? How to determine one’s path in practice with parents? What should be the nature of the “family interview”?

The “family interview,” after all, is an institutional apparatus which suggests a certain standardization of analytic practice. And yet, I am free to determine the length of the session. The exact hour of commencement is fixed by institutional agenda but the end of the session is decided upon by the discourse of the parents. Thus the question can be reformulated in these terms: on what elements in the parents’ discourse would depend the end, the cut of the session?

To have a sketch of a response to this, I propose that we consider a crucial notion in the symbolic register, namely, the notion of misunderstanding.

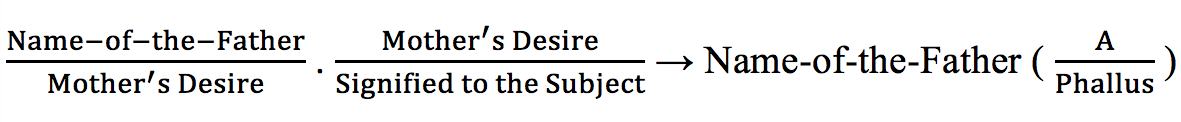

The animal world is a world where there is no symbolic. It is a world where one cannot speak, one cannot go astray, one cannot deceive and where there is no equivocation and misunderstanding. Hence crucial point, that in the animal kingdom, there is communication for sure but that does not constitute a language which can be formalized by structural linguistics, namely “a group of elements forming a covariant set” as Lacan puts it in the Seminar on The Psychoses (1955-56)(183). Communication between animals is by the sign and by the signifier, whose fundamental characteristic is equivocation, misunderstanding: the fact that what we say we do not understand. It is a structural fact: “misunderstanding is the very basis of interhuman discourse” as Lacan contends (Psychoses 163). The bar that separates the signifier and signified in the Saussurian algorithm is:

(66, 114)

Misunderstanding, generally speaking in the human domain, could be understood by considering a plurality of languages: we arrive in a foreign country and do not understand what the native speakers are saying. In the animal world on the other hand, communication is effective. The honeybee indicates by making a bi-univocal sign the exact position of the flower, and it can do this anywhere in the world. Animal communication is mostly by the sign, as an index for a presence as the signifier is an index for an absence and as explained by Lacan inspired by Kojève’s lecture on Hegel, “the symbol first manifests itself as the killing of the thing” (“Function and Field” 262).

Human language introduces the fact that we do not understand each other, it introduces equivocation and misunderstanding. Moreover, from the first cry of the infans when the cry is transformed into an appeal, misunderstanding is characterized by the passage of need through demand addressed to the Other. In Bruce Fink’s words:

[…] The essence of communication is miscommunication. In Lacan’s own words, ‘the very foundation of interhuman discourse is misunderstanding [malentendu].’

[…] Since the infant’s speech is quite inarticulate, people must interpret its crying. A baby cannot be said to know what it wants when it cries; the meaning of that act is provided by the parents or caretakers who attempt to name the pain the child seems to be expressing. […] Meaning is thus determined not by the baby but by other people – that is, by the Other.(235)

The satisfaction of need, on which the survival of the child depends, relies on the interpretation that parents make of the child’s cry to transform it into an appeal, introducing the dimension of misunderstanding, which is fundamental to the interhuman discourse. However, as Jean-Michel Vappereau has noted, the dimension of misunderstanding in Lacan’s final teaching is also at the heart of the Lacanian notion of traumatism, punned as “troumatism” (where “trou” means “hole”):

The traumatism (troumatisme) of the misunderstanding [malentendu] of the parents… They do not understand the infant’s cry. Hole which, from that point on, constitutes the sinthome.

(“Making Rings” 337)

In June 1980, in his last seminar entitled Dissolution! (1980), Lacan broached the question of traumatism before he left Paris for Caracas, in a session simply entitled “Misunderstanding” [“Le Malentendu”]:

This is something that Freud passed on to you. What a strike, one should say. As much as you all are, what are you other than misunderstandings? One named Otto Rank approached it while talking about the trauma of birth. There is no other trauma: man is born misunderstood. Since I am asked what the basis of the body is, I come here to underline that it is only hooked there. The body appears in the real only as misunderstanding. Let us be radical now: your body is the fruit of a lineage and a good part of your misfortunes is linked to the fact that your lineage was already swimming in as much misfortune as possible. It was swimming for the simple reason that it might speak as much as it could. This is what your lineage has transmitted to you “giving life” as one would say. It’s this that you inherit. And it’s this which explains the malaise on your skin, and that’s how it is. Misunderstanding is there already, well in advance. And so far as an earlier period to this beautiful legacy is concerned, you already belong, or rather you are already part of your ancestors’ stuttering speech. In fact, it’s not even a necessity that you stammer yourself. Even earlier, what sustains you in the name of the unconscious is misunderstanding, rooted in this place. There is no trauma of birth other than being born as desired.

Desired or not–– it’s the same thing since it is by the parlêtre. The parlêtre in question, generally splits itself into two speakers. Two speakers who do not speak the same language. Two who do not hear each other speak. Two who don’t listen at all. Two who conjure up a reproduction out of a successful misunderstanding that your body will transmit with the same reproduction.

(12-13)[1]

This is what traumatizes the child, being desired…or not, according to Lacan. The symptom of the child is constituted by the process of appropriating signifiers that transmit the desire of the parents. The symptom of the child, as Lacan highlights in his “Note sur l’enfant” [“Note on the Child”] written in 1969, is like the representation of truth: “the symptom can represent the truth of the familial couple” (373). If we follow Hélène Deltomb’s argument, this truth that the symptom represents is simply the misunderstanding between parents:

By their desire, its [the child’s] parents give it a place, and here the child manifests the dimension of truth by its behavior and speech. While appropriating the signifiers of its father and its mother the child becomes a carrier of misunderstanding between the parents, one that the child translates into a symptom and one it cannot decipher because it is alienated in this place.

(Deltomb)

The encounter with the opaque desire of the parental Other leaves open, that is to say, in a non-programmed, non-predetermined fashion, the manner in which the child interprets and responds to this desire. What the child encounters here is an enigma, the enigma of the Other’s desire in its place. This explains such repetitive, relentless questions like: “You are saying this to me, you are saying this to me, why are you saying this to me?” In fact, near ones can easily become total strangers to each other in the opacity of their desire. This is the extimacy of the parental Other. As the child experiences the enigmatic desire of its parents it becomes a carrier of misunderstanding: “There is no other trauma: man is born misunderstood,” as Lacan had observed.

In 1980 in his last seminar, Lacan advanced a notion that retroactively perfected his teaching, arguing that one is already traumatized by the desire of one’s parents. This is what he named earlier as the “infinite straight-line” [“la droite infinie”] or the “I.S.” [“D.I.”]. As Jean-Michel Vappereau adds during the “Discussion” session of Cyril Veken’s “Exercice de lecture” anthologized in La Parole et la Topologie (2015[2012]):

The infinite straight-lines, Lacan told us, it’s Urverdrängt, it’s the child when it perceives that its parents don’t listen to its cry and is traumatized. And Lacan puts it very elegantly when he says that the child is traumatized because the parents misunderstand, because ‘they don’t hear the cry […] the entry into language, the trauma, Urverdrängt, […] it’s the infinite straight-line, this is a real hole.’

(Quoted in Cyril Veken et al, Ch. 2)

The infinite straight-line is a real hole that helps take note of the traumatism that is a “troumatism,” being the entry of the infans into language and which corresponds to what Freud called primal repression (Urverdrängt). Jean-Michel Vappereau puts it more precisely in a lecture entitled “La D.I.”:

Lacan waited for the last session of his Paris seminar to provide us with his doctrine of trauma by which the subject who speaks becomes what it hears with its ears: a subject of language. It is called the trauma of Misunderstanding of which he [Lacan] had already been speaking from the very beginning each time he referred to madam F. Dolto [Françoise Dolto]. He speaks of parental misunderstanding which does not understand the cry. This is Freud’s Urverdrängt, primal repression, the real hole which Lacan had represented in writing with the infinite straight-line, which he wrote as I.S. It’s the hole we can’t think of, faced with the infinite straight-line this hole is around it and we are in between. It’s the same for that which we forget, it constitutes us and that’s how it’s impossible to think of, it is the real.

(“La D.I.”)

In his very last lesson, Lacan reformulates the fundamental concepts of psychoanalysis from a nodal structure to knowing the Borromean knot, that is to say, a knot of three that is always about to collapse and which also presents the three registers of the speaking being: the imaginary, the symbolic and the real. If this knot is always falling apart this is because man is “ill made.” Man is “ill made” because he goes into the world bathed in language. His birth is a plunge into the bath of language, that is to say in a symbolic world in which one does not understand oneself, which introduces equivocation and misunderstanding. Sexual reproduction, the act that makes children, constitutes a paradigmatic example of misunderstanding. It is for this reason that Lacan in his final seminar considers misunderstanding as the very principle of childbirth. In fact, to put it better, one does not know if the child is for the father or for the mother, and is not necessarily the same thing for each of them, they do not understand each other and the child too is a product of this misunderstanding. Being a product of misunderstanding, Jacques Borie thinks, is not a barrier. In fact, it is the human condition:

To be misunderstood is not a barrier, on the contrary it is the human condition. It’s when you know more, that there is danger. It’s when the child understands far too much that things become complicated. One can say that this is why the autistic child or the psychotic has the advantage of becoming a child who knows too much, that is to say he knows which place he is in, knows where he is wanted, knows what is wanted of him that he should to be of a certain kind and that he can’t be otherwise, no misunderstanding is possible. Knowledge becomes absolute.

(Borie)

The autistic subject, can perhaps be considered like a child who understands too much, where no misunderstanding is possible between parents. This question of misunderstanding within the clinic of autism, following Jean-Michel Vappeareau’s work, can be approached by considering the difficulties the autistic subject experiences in inscribing itself in the register of narcissism:

What is narcissism? It is the difficult but necessary experience for maintaining in life even momentarily, a premature body, a fetus of an ape coming to sexual maturity. This is a reunion of two ahistorical components:

Of trauma: misunderstanding on the part of parents who do not understand the cry (Lacan’s last lesson in his 1980 Paris seminar), the discovery in the child of the power of speech as misrecognized enunciation by the parents, one that is rejected by the autistic subject […](“Le narcissisme”)

The autistic child can thus embody a subject who knows too much. In the clinic of autism, as a consequence, a psychoanalytic practice can hope to exploit misunderstanding. In fact, in this last lesson of his seminar on Dissolution! Lacan contends that: “for the psychoanalyst, his expertise lies in exploiting misunderstanding; at the end there is a revelation, that of fantasy” (Dissolution! 12). The psychoanalyst’s task is to exploit misunderstanding and not dissolve it. Without seeking to dissipate misunderstanding he gives him his true logical status: the misunderstanding of structure. To wish to dissolve misunderstanding is to suppose that there is a place where it is possible to finally understand everything. And all of a sudden, Lacan underlines, if one looks to dissolve it one finishes by nourishing, reinforcing it:

I hold on to this seminar less than it holds on to me. Is it through habit that it holds on to me? Surely not, but rather is by misunderstanding. And it is not about to end, precisely because I’m not used to this, to this misunderstanding. I am traumatized by misunderstanding. Because I do not get used to it, I fatigue myself to dissolve it. And all of a sudden, I have nourished it.

(12)

Misunderstanding is thus something that we cannot utilize with the purpose of dissolving it but one that we should use to produce something else with it. There are many ways to produce misunderstanding. There are those that put us on an impasse while those which help us create something new, something original, be it in the field of human knowledge or in the field of artistic creation. And this can be applied also to the clinic: exploiting misunderstanding between parents and children, and it’s especially this last that we can do exploit more. It of course means to resonate misunderstanding within multiple facets of the signifier, as well as within the link that the signifier maintains with the body. The child, the “parlêtre in question,” as Lacan calls it, which “splits itself into two speakers. Two speakers who do not speak the same language. Two who do not hear each other speak. Two who don’t listen at all” (Dissolution! 13). Hence, for a man and a woman to agree on something, it is essential that they do not speak the same language.

And this can also orient our institutional practice. In fact, one hears frequently that among educators working within institutions that receive autistic or psychotic subjects that the child “finds the fault in the institution” ––– for example when the educators do not agree with each other on how to manage such a child or such a situation. And it is also frequently said that during institutional supervision where the team ought to appear unified and coherent while managing such a situation. The advice in such a case can be this, that if the educators do not agree with each other, they should manage the matter among themselves, elsewhere or later, but one should certainly not show the child that they are in disagreement because “it makes him mad,” as we hear so often. The interpretation of adults of such and such behavior or such and such wish of the child, is thus one and one only. It is that which justifies the recourse to the specialist, to the supervisor and to the expert. That is to say, to absolute knowledge. This practice is precisely what dissolves misunderstanding in institutions. However, if we seek to exploit misunderstanding, we ought to encourage such a discord, to exploit such disagreements, such misunderstanding to precisely preserve the possibility of working on a common platform with the child. Thus in such institutions, the child can look to search for a gap, a distance, between those who are working with him, and this is a crucial question for the child, because it is exactly in such a gap that it can find a path to orient and protect itself from the distressing intrusion of an absolute Other reduced to One.

Following this logic, the “family interviews” at the center of the institution can be organized precisely to exploit the misunderstanding between parents, while searching for the break between the desire of each one vis-à-vis their child. This break can emerge and can be found by being attentive to the desire that can be heard behind the demand of each of the parents’ addresses to the institution. And it is at this moment that a separation, a distance or a space can suddenly open up within parental discourse, and the cut of the interview session can punctuate this break, and allow the child to lodge itself like a subject in this fault-line and find its own path in life.

Translated by

Dipanjan Maitra

Note

1. Translator’s Note: All excerpts from “Le Malentendu” / “Misunderstanding,” i.e. session of 10 June 1980 from Lacan’s seminar entitled Dissolution! (1980) have been translated from the French original as they appeared in Ornicar? Bulletin Périodique du Champ Freudien, N° 22-23, Spring 1981, 11-14. The translator wishes to thank Freud-Lacan scholar Richard G. Klein for providing access and helping compare two other translations of the same session by Bracha Ettinger and the version published in Papers of the Freudian School of Melbourne, PIT Press, 1981. For bilingual versions of similar texts and articles on psychoanalysis see Klein’s website : https://www.freud2lacan.com/. ↩

Borie, Jacques. “La question paternelle est-elle encore d’actualité?” 20 January 2018, Valence.

Web. May 13 2018. Retrieved from: http://www.radiolacan.com/fr/topic/1137/3.

Deltomb, Hélène. “Interpréter le symptôme de l’enfant.” Web blog post. Journée de l’Institut de

l’Enfant, 21 March 2015. Web. May 13 2018. Retrieved from:

http://www.causefreudienne.net/interpreter-le-symptome-de-lenfant/

Fink, Bruce. A Clinical Introduction to Lacanian Psychoanalysis: Theory and Technique.

Cambridge, Massachusetts & London: Harvard University Press, 1997. Print.

Lacan, Jacques. Le Séminaire de Jacques Lacan: Livre: XXVII: Dissolution! Leçon du 10 juin

1980, “Le malentendu,” Ornicar? Bulletin Périodique du Champ Freudien, N° 22-23,

1981. 11-14. Print.

---, The Seminar of Jacques Lacan: Book III: The Psychoses. Ed. Jacques-Alain Miller.

Translated by Russell Grigg. New York and London: W. W. Norton & Co., 1997. Print.

---, “Note sur l’enfant.” Autres Écrits. Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 2001. 373-374. Print.

---, “On a Question Prior to Any Possible Treatment of Psychosis.” Écrits: The First Complete

Edition in English. Translated by Bruce Fink. New York and London: W.W. Norton &

Co, 2005. 445-488. Print.

---, “The Function and Field of Speech and Language in Psychoanalysis.” Écrits: The First

Complete Edition on English. Translated by Bruce Fink. New York and London: W.W.

Norton & Co, 2005. 197-268. Print.

Marret-Maleval, Sophie. “Un impossible accord: amour et non-rapport sexuel.” École de la

Cause Freudienne. Web. 13 May 2018. Retrieved from:

http://www.causefreudienne.net/un-impossible-accord-amour-et-non-rapport-sexuel/

Saussure, Ferdinad de. Course in General Linguistics. Edited by Perry Meisel and Haun Sassy.

Translated by Wade Baskin. New York: Columbia University Press, 1959. Print.

Vappereau, Jean-Michel. “Making Rings: The Hole of the Subject in the Embedding of the

Topology of the Subject.” Ellie Ragland and Dragan Milovanovic eds. Lacan: Topologically Speaking. New York: Other Press, 2004. 328-360. Print.

---, “La D. I.” 15 September 2013, École Lacanienne de Montréal. Web. Retrieved from:

http://www.ecolelacanienne.org/pdf/ProgrammeVappereau_sept2013.pdf

---, “Le narcissisme n’est pas un vilain défaut…” 14 September 2013, École Lacanienne de

Montréal. Web. Retrieved from:

http://www.ecolelacanienne.org/pdf/ProgrammeVappereau_sept2013.pdf

Veken, Cyril et al. La parole et la topologie: Pourquoi et comment la parole implique-t-elle la

topologie? Paris: Éditions Modulaires Européennes, 2015. Kindle Book.

Alejandro Olivos

Clinical Psychologist and Psychoanalyst

janoolivos@gmail.com

© Alejandro Olivos 2018