‘Penny-wise…’: Ezra Pound’s Posthumous Legacy to Fascism

Andrea Rinaldi and Matthew Feldman[1]

Introduction

Certainly a leading American modernist at his death in 1972, aged 87, Ezra Pound’s influence continues to extend far beyond poetry. Although almost entirely neglected by Pound Studies another, the darker side of Pound’s legacy is charted here.[2] As this unlikely case study demonstrates, Pound has inspired ideologues of post-war, or “neo” fascism (often taxonomically understood as the ‘extreme right’, which will be used here as an umbrella term) – on both sides of the Atlantic, both during his lifetime and since. This article argues that Pound remains an important touchstone upon different shades of extreme right thought – most notably in the US, Britain and Italy; places where he spent more than a decade of his long life. Whether in British, Italian or American contexts, Pound’s political views have an unexpected relevance to the international networks and converging ideas that recent scholarship has helpfully understood in terms of “transnational fascism.”[3]

It is widely agreed that disgust at the economic meltdown of the 1929 “Great Depression,” by no means an exclusively fascist attitude, brought Pound’s economic ideas to a boil in the 1930s, intensifying his pre-existing vitriol against bankers, financiers and (increasingly Jewish) usurers between the wars. In fact, During World War I Pound lost two of his best friends, including the leading intellectual of The New Age, T.E. Hulme, and the sculptor Henri Gaudier-Brzeska. This, combined with the huge and terrifying death toll in the war itself, had a strong effect on Pound’s sensitivity and, eventually, upon his political convictions. The idea that the Great War revealed a “botched civilization,” and “old bitch gone in the teeth” as Pound wrote in his 1920 sequence, Hugh Selwyn Mauberley, would drive him toward the putatively social, political, and above all, economic causes of the conflict.

In fact, in the year after the war’s conclusion, Pound met Clifford Hugh Douglas, a retired Scottish engineer who had devoted himself to the construction of the project of social and economic reform known as “Social Credit.” The meeting took place at the editorial offices of the The New Age magazine, where Pound was the only regular salaried employee. More than this, Orage was the first to try popularise Douglas’ ideas through the magazine. In the 1920s the journal’s Guild Socialist background was to become the principal means of diffusion for Social Credit theory (Marsh 80-110). In Pound’s mind, Douglas’ project gained a much wider significance, and became part of a larger program for a new cultural and social renaissance that was to be ultimately inextricable from fascism in Britain, the US, Italy and even Nazi Germany. Increasingly, for Pound, fascist Italy came to represent a key example of his economic ideas into and, consequently, the best prospect for a spiritual renaissance of the Western civilisation. From Pound’s point of view, Italian Fascism was capable of instigating the new, occidental renaissance because of its alleged superiority over both democracy and communism. As maintained long ago by Niccolò Zapponi:

In the political events surrounding Ezra Pound we can perhaps identify the unique case of a man of letters who came to sympathise with fascism via the economy: for nearly twenty years, the American poet advocated the absolute need for monetary and taxation reforms, and believed that Italian Fascism was oriented towards their gradual implementation. In practice, this was not true in any way, but the actual reality of the policy never effected Pound’s conviction that Mussolini was an economist of genius (Zapponi 11).[4]

Thus, argues Zapponi, Pound became a sort of a “Buddhist monk of the republican fascism” who, despite his extraordinary “acts of faith” in fascism, could not recognise that, under Mussolini, the Italian political economy scarcely took the direction advocated by Douglas. Accordingly, the large amount of publications Pound dedicated to Italian economics – including the notorious months of the Salò Republic – show him praising Fascism’s adoption of Douglas’ theories (Zapponi 32-47).

Furthermore, recent scholarship has argued that, for much of his life, Pound was a committed fascist ideologue and anti-Semite – at his peak, acting as a key propagandist for what he termed, in one talk, “The United States of Europe” – delivering perhaps as many as two thousand radio items for the wartime Axis.[5] One revealing and representative example must suffice at the outset here, taken from Pound’s widely available transcripts reproduced in Leonard Doob’s 1978 collection of 120 radio broadcasts, Ezra Pound Speaking:

You with your cheatings and with your Geneva and sanctions, set out to crush it, in the SERVICE of Jewry, though you do not even yet KNOW this. And you have not digested the proposals or instructions of Jewry. And you have NOT understood fascism, or nazism for that matter. Very few of you have read the writings of either leader. It is and has been for 20 or more years, God knows, nearly impossible to print news from or to Italy or translations from Italy in your country. You have NOT read Mussolini, and I don’t suppose you could now get hold of his speeches in coherent order: not many of you; or understand the points and situations that they apply or applied to.[6]

This excerpt exemplifies Pound’s wartime vitriol on behalf of the Italian Fascist regime. There are many similar passages in Doob’s collection, which itself only scratches the surface of his activism for the Axis. As a result of these activities, Pound was ultimately imprisoned for twelve and a half years in St Elizabeths asylum after the Second World War.[7]

Emblematic of his continued support for fascism, upon his release and return to Italy in late June 1958, Pound made the fascist salute to waiting reporters. Nowadays, the famous shot is proudly exhibited on the web page of group of artists who gather around CasaPound Italia, the neo-fascist group described below (see image).[8]

Celebrating his arrival were a group of neo-fascist activists for the Movimento Sociale Italiano and “over-enthusiastic nostalgics for the old regime who”, in the words of his long-time friend and protégé John Drummond, “would like to transform your arrival into a political triumph”. In his letter of 5 June 1958, Drummond continued: “There was even a scheme to have you taken off the ship at Naples and borne north in triumph in a fleet of escorted cars, banners and gagliardetti flying, etc.”; moreover, in Italy, the

present neofascist parties may or may not have something to be said for them, though my own opinion is that they are quite unworthy to represent any of the things that were good in Fascism, and might still have validity today. But the point is that their motives for wanting to make a political celebration of your return are wholly self-interested, and for this reason alone they should not be given the chance (Drummond).

Following his release from St Elizabeths in 1958 Pound returned to Italy, where he resumed contact with a number of far-right ideologues including Valerio Borghese, Vanni Teodorani and Ugo Dadone. On, the latter, one of Pound’s biographers, Humphrey Carpenter, has noted that, in Spring 1961, Pound stayed with Dadone, who

was involved with the neo-Fascist Movimento Sociale Italiano and regularly wrote articles about them in right-wing journals. They held a May Day parade, wearing jack-boots and black armbands, displaying the swastika, shouting ant-Semitic slogans, and goose-stepping. Among those photographed at the head of the parade was Ezra. (Carpenter 873-874)

Also in 1961, on 20 March Pound attended a press conference in Rome held by, Sir Oswald Mosley.[9] Since founding the Union Movement several years after his release from wartime internment (as the leader the British Union of Fascists and National Socialists, or BUF), the latter advocated a decidedly “transnational fascist” concept of “Europe a Nation” in his post-war journal, The European – of which more below – or as Pound told reporters that day, “he believed that the day would come for European unity, a concept wholly endorsed by Mosley” (Hendreson 164).[10] These instances from 1961 alone suggest that these activities were scarcely the last time Pound’s political activism was instrumentalised by extreme right ideologues with pretentions of international influence.

More specifically, this article considers three distinct strands of the post-war extreme right since the Axis denouement of 1945 that have explicitly, and repeatedly, emphasised their Poundian influence. In doing so, this contribution can only scratch the surface of what is an unusually diverse legacy amongst the post-war extreme right. The first of these strands, white nationalism and biological anti-Semitism, is most often associated with neo-Nazism; namely, the attempted ideological preservation of values and traditions from the Third Reich, above all its symbols and belief in a Jewish conspiracy. A second strand, conscious of the stigma of the Axis war and Holocaust, has long flourished in post-war Europe. It typically traces its legacy to non-Nazi forms of fascism; most notably those associated with Mussolini’s Italian Fascism, and represents deliberate attempts to update fascist ideology through studious revision, even selective rejection, of past fascist policies. This is sometimes referred to as “Fascism of the Third Millennium,” which may be best observed in the case of explicitly fascist movement CasaPound Italia – a movement so indebted to Pound’s legacy that his daughter, Mary de Rachewiltz, has threatened litigation for using the poet’s name for unabashedly fascist purposes.[11] Finally, a third strand touched upon here, represented by Britain’s New Right, emphasises European “Tradition” and a metapolitical, ideas-driven ideology that has similarly championed Pound as a kind of cultural martyr for fascist ideas during and after WWII. Albeit briefly given the constraints of space and scope, each of these three “faces” of post-war fascism will be considered through the surprisingly significant legacy of a leading modernist poet turned extreme right ideologue.

Naturally, Pound’s legacy is not of the same influence or character as the key fascist pantheon post-war ideologues like Hitler and Julius Evola, or even lesser-known figures like Oswald Mosley or Colin Jordan. This is largely due to the fact that academics debating Pound’s influence upon right-wing extremists have confined themselves to the effective diffusion – or otherwise – of Pound’s poetry and prose within the extreme right circles. Academics believed, rightly, that most of these extreme right activists and sympathizers would neither understand nor really appreciate texts like Guide to Kulchur or The Cantos which, on the whole, seems to have led to an underestimation of neo-fascist appropriation of Pound. All the same, in an aside many years ago, one of the leading Poundian scholars, Massimo Bacigalupo, noted that Canto LXXII and Canto LXXIII, the only Pound composed during the war and the only two wholly in Italian, as it were, to employ John Lauber’s characterisation, a kind of “fascist epic” (Bacigalupo x).[12] Nonetheless, these have remained minority views amongst the mountainous scholarship on Pound’s poetry.

Yet Pound’s infamous case remains relevant to the extreme right beyond his literary production and his radio-propaganda. Indeed, his life as a fascist ‘martyr’ is what really impressed the audience of the contemporary extreme right. Pound’s 13-year punishment for the fascist cause is a significant legacy in its own right. The alleged hypocrisies of incarcerating (mostly in a sanatorium) a non-convicted man, in fact, became an iconic example for right-wing extremists, one far more significant than the esotericism of The Cantos.[13]

Pound and the Anglo-American Extreme Right since 1945

In the wake of his arrest on treason charges in 1945, Pound was declared insane and institutionalised until 1958. Drawing upon his earlier interwar relationship with the BUF, from his residence at St Elizabeths asylum near Washington, D.C, Pound both raised money and smuggled out texts for Oswald Mosley’s neo-fascist Union Movement.[14] This extended to publishing several texts in the organisation’s short-lived house journal, The European – including the first publication of Canto CI and several shorter texts. This short-lived publication (1953-1959), touting “Mosley’s concept of ‘European Socialism’, which he wished to be accepted as a common programme for all European fascist movements”, additionally, in Graham Macklin’s words, “The European served as a crucible for a number of young fascist ideologues, like Desmond Stewart and Alan Neame […] writers fixated with the poetry of Ezra Pound” (Macklin 135-136). Amongst the younger fascists in Mosley’s stable responding to Pound’s work were Denis Goacher, Harvey Black, Desmond Stewart and, most fervently, Alan Neame. The latter, for example, had been corresponding with Pound since 1947, and had written no less than 7 texts in The European on Pound’s celebrated sequence from 1946-1946, The Pisan Cantos, a poetic apologia for his wartime activism on behalf of the Axis:

Saints, martyrs and divine kings are not the only people to rule from the tomb; and poets sometimes rule from the prison house [...] if we live in the Era of the Asylum, it is only so because it is at the same time the Era of the International Loan with Strings Attached (Neame 357-360)

Interestingly, Pound’s British influence extended beyond the United Kingdom to the post-war Commonwealth as well. This is especially the case with the Australian writer, Noel Stock, a one-time devotee who was tirelessly seeking to establish Pound’s place in modern English verse – and extreme right politics. In 1953, Stock wrote to the leading modernist critic, Hugh Kenner, who advised him to get in contact directly with Pound. Even if the two only met personally in 1958 in Brunnenburg Castle – Mary (Pound’s daughter) and Boris de Rachewiltz’s residence in the Italian Tyrol – Stock and Pound had an extended correspondence of “more than a hundred letters (between forty-five and fifty thousands words)” during the previous five years. While his 1970 The Life of Ezra Pound remains the gold standard of Pound biographies, in the preface Stock nevertheless asserts:

I well remembered Kenner’s warning in 1954 to be careful of Pound’s politics; I paid little heed and was soon involved is Social Credit and similar activities. I joined a Social Credit newspaper, The New Times, and to Pound’s great satisfaction began to publish unsigned or pseudonymous items which he sent from Washington (Stock xiii).

Doubtless encouraged by Pound, Stock contributed two texts to The European’s final issue in 1959, the first revealingly entitled “Blackout on history,” a phrase used by Pound The Pisan Cantos. The phrase, in turn, is almost certainly a reference to Harry Elmer Barnes’s introductory chapter, “Revisionism and the Historical Blackout” from his 1953 Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace. For his part, Barnes is notorious as an American pioneer of Holocaust Denial writings – or what he fancifully dubbed “WWII revisionism”. That this was simply an ideological repackaging of fascist anti-Semitism is made clear by the likely source for Barnes’ 1953 chapter; namely, The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion (which Pound had already read and repeatedly praised during the Second World War). This notorious Tsarist forgery has been traced by Archie Henderson as Pound’s inspiration for his, and subsequently, Stock’s, use of the phrase “blackout on history”:

On the historical blackout, see Protocol 16.4: “Classicism as also any form of study of ancient history, in which there are more bad than good examples, we shall replace with the study of the program of the future. We shall erase from the memory of men all facts of previous centuries which are undesirable to us, and leave only those which depict all the errors of the government of the GOYIM.” (Pound, Agresti, Henderson 509-510)[15]

In his aforementioned article from 1959, Stock went so far as to praise Barnes as the “one professor who has made a fight for some sort of decency inside the historical profession”. Stock concludes, through veiled anti-Semitic reference preferred in The European to open Judeophobic references: “My purpose here has been to indicate that history is largely in the hands of men who in many cases seem to be hamstrung by attachment to ‘vested interests’.” (Stock, Blackout 337, 343). Linking these more opaque phrases to explicitly fascists writings, moreover, only two years earlier, Stock had also published Pound’s translation of Benito Mussolini’s summer 1943 diary composed while under house arrest, “In Captivity: Notebook of Thoughts in Ponza and La Maddelena”. This anonymised text appeared in Stock’s Australian journal, Edge (appearing in 1957-1958); that is, at a time when Stock was clearly receptive to the neo-fascist ideas circulating amongst the Poundian acolytes at St Elizabeths.[16] Likewise revealing Pound’s transnational relevance to neo-fascism today, another Antipodean extreme right ideologue, the New Zealander Kerry Bolton, has published a short biography of Pound at Oswald Mosley’s homage website – still hosted by the far-right ‘Friends of Oswald Mosley group – affirming in the final paragraph: “On 30 June 1958, Pound set sail for Italy. When he reached Naples, he gave the fascist salute to journalists and declared ‘all America is an asylum.’ He continued with The Cantos, and stayed in contact with political personalities such as Kasper and Oswald Mosley.”[17]

Yet Stock was not the first biographer to sit at the feet of the modernist patriarch; rather, it was the American conspiracy theorist Eustace Mullins – another pivotal transnational figure on the post-war extreme right. Since Mullins’s death in 2010, a devotional website has been launched, republishing many works following his 1962 biography This Difficult Individual, Ezra Pound. Perhaps unsurprisingly, one text not included on this site was published only a year before Mullins’s white-washing biography, entitled “Adolf Hitler: An Appreciation”. Rather than explicit neo-Nazism – which Mullins never recanted, in fact – pictures of Pound festoon the homepage at www.eustacemullins.us, including the latter’s infamous mugshot – taken in captivity on 26 May 1945 (see image[18]).

Further underscoring this connection with the poet is Mullins’s biography, found on the homepage:

Eustace Mullins (born 1923) is an American political writer, author, biographer, and the last surviving protege of the 20th century intellectual and writer, Ezra Pound [….] Mullins was a student of the poet and political activist Ezra Pound. He states that he frequently visited Pound during his period of incarceration in St. Elizabeth’s [sic] Hospital for the Mentally Ill in Washington, D.C., between 1946 and 1959 [sic - Pound was released in June 1958]. Mullins claimed that Pound was, in fact, being held as a political prisoner on the behest of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Mullins’ most notable work, The Secrets of the Federal Reserve, was commissioned by Pound during this period.[19]

Tellingly, at the time of writing Pound’s biography Mullins headed the Aryan League of America – upon whose headed stationary Mullins corresponded with Pound at St Elizabeths during the 1950s. According to the neo-Nazi right activist, Pound expressly started him on the first of his conspiratorial writings, The Secrets of the Federal Reserve, paying him “ten dollars a week” and hosting him at St Elizabeths Hospital during the book’s research in the nearby Library of Congress. This is highlighted by the following Preface, added to the book in 1985:

Here are the simple facts of the great betrayal. Wilson and House knew that they were doing something momentous. One cannot fathom men’s motives and this pair probably believed in what they were up to. What they did not believe in was representative government. They believed in government by an uncontrolled oligarchy whose acts would only become apparent after an interval so long that the electorate would be forever incapable of doing anything efficient to remedy depredations.

(AUTHOR’S NOTE: Dr. Pound wrote this introduction for the earliest version of this book, published by Kasper and Horton, New York, 1952. Because he was being held as a political prisoner without trial by the Federal Government, he could not afford to allow his name to appear on the book because of additional reprisals against him. Neither could he allow the book to be dedicated to him, although he had commissioned its writing. The author is gratified to be able to remedy these necessary omissions, thirty-three years after the events.) (Mullins, The Secrets 85).

Whether or not Pound explicitly considered him as his protégé, it is clear that their relationship was both close – especially in the 1950s – and of primary importance for Mullins over the ensuing decades of extreme right activism.

One influence upon Mullins during Pound’s incarceration, surely, was the encoding of anti-Semitic conspiracy theories. Accordingly, the word ‘Jew’ does not appear in The Secrets of the Federal Reserve – favouring the dog-whistle term ‘international financiers’ instead – although Mullins was to become much more explicit in his prejudices after Pound’s death. In fact, Mullins’s publications became increasingly anti-Semitic as his star began to rise in the US neo-fascist firmament. Thus, works over the ensuing decades extended Jewish TV: Sick Sick Sick and Mullins’ New History of the Jews, which opens: “Throughout the history of civilization, one particular problem of mankind has remained constant. In all of the vast records of peace and wars and rumors of wars, one great empire after another has had to come to grips with the same dilemma… the Jews.” Later, contributing to perhaps the most enduring anti-Semitic conspiracy of the twentieth century, Mullins’s chapter “Jews and Communism” then avers:

The poet Ezra Pound, who criticized the Jews for plunging the world into the horrors of the second world war, spent thirteen years in the Hellhole of St. Elizabeths, a Federal mental institution in Washington, D.C. for political prisoners. Pound won a number of prizes for his writings while the Jews had him locked up as a madman. Many visitors to the ward, including this writer, commented that the stench of the place was exactly like that of the cities in Europe which had fallen to the Jewish Communists (Mullins, New History 101).

This was not the only conspiracy theory Mullins was spinning as a leading ideologue of the extreme right, both in the US and internationally. Only a year earlier, Mullins argued in The Secret Holocaust that Jews had been engaged in genocidal activity toward gentiles long before the Second World War. But that was not to say the Nazis’ attempted Judeocide was justified; instead, Europe’s Jews had conspired to construct the Holocaust to elicit sympathy and financial reparations after 1945. As one of the earliest Holocaust deniers in the US – alongside Harry Elmer Barnes, to be sure – for Mullins, this ruse “might have more validity had it not been for one unfortunate oversight by the Jews – they did not build the gas chambers at Auschwitz until after World War II had ended” (Secret Holocaust). In keeping with Pound’s turn toward the US movement of white supremacism – to the extent of assisting the Ku Klux Klan in the mid-1950s in attempting to retain the segregation of American schools following the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling – Mullins similarly linked US racial desegregation to alleged Jewish control and rejection of ‘Aryan’ values. In a text decrying Mullins’s “notorious” “anti-Semitism/racism,” Richard Abanes has recently cited the following texts and influences:

Proof of Negro Inferiority, which compares African Americans to gorillas; Who Brought the Slaves to America, a study ‘proving’ that the Jews were responsible for America’s slave trade; and The Hitler We Loved and Why, a pictorial exposé on why Germans loved Der Führer. Mullins directly blames international Jewish bankers for the world’s evils and imputes all of America’s troubles to the Jews, even such problems as rising medical costs and difficulties in the health care system. Mullins’s beliefs came from Ezra Pound, a staunch anti-Semite who, according to a 1982 Aryan Nations Newsletter, was ‘a great admirer of Adolf Hitler and Mussolini.’ Mullins boasts about visiting Pound ‘every day for three years,’ saying each day Pound lectured him on world history. Mullins admits, ‘That’s how I found out what I know’ [italics added] (Abanes).

Given Mullins’s decades-long trafficking in Holocaust denial, it should come as no surprise that, as his hagiographic website avers, he was on the “editorial staff of far-right Willis Carto’s American Free Press. He is also a contributing editor to the Barnes Review” – the latter, of course, named after the aforementioned Harry Elmer Barnes.[20] As the publisher of the American Free Press and The Barnes Review, Willis Carto’s Liberty Lobby has long acted as the main disseminator of Holocaust ‘revisionism’ – both in book and serialised form. Which is to say, of course, that Carto’s veneration for Pound is likely less his poetic achievements than his extreme right politics, as the following vignette from the late Christopher Hitchens underscores:

I was once introduced, in the Cosmos Club in Washington, to Willis Carto of the Liberty Lobby, a group frequently accused of being insufficiently philo-Semitic. Mr Carto unburdened himself of quite a long burst about the power of finance capital, whereupon our host, to lighten the atmosphere, said, ‘Come on Willis, you're sounding like Ezra Pound’. ‘Ezra Pound!’ exclaimed Mr Carto. ‘Why, I love that man's work. Except for all that goddam poetry!’ I thought then that if one ever needed a working definition of an anti-Semite, it might perhaps be an individual who esteemed everything about Ezra Pound except his Cantos.

It bears noting that The Barnes Review, and especially its parent organisation, The Institute for Historical Review (IHR), has remained the most influential publishing outlet for the transnational extreme right for decades. In this light, Carto’s otherwise curious interest in modernist poetry becomes explicable, as George Michael’s recent study maintains:

In the realm of literature, Carto exalts Ezra Pound as one of America’s greatest poets, and for heroically opposing FDR’s pubs for war in Europe. Pound’s service as a radio propagandist in Fascist Italy is characterised as an admirable effort to inform Americans that their system of government and society had been taken over by ‘alien forces dedicated to achieving their own goals, trampling over American interest in the process (Michael, Willis Carto 154).[21]

Despite the linguistic encoding so readily identified by Hitchens and others, the identity of these conspiring “alien forces” is undoubted and in keeping with the overwhelming majority of Holocaust ‘revisionists’: Jews. Moreover, given the confluence of Holocaust denial and devotion to Ezra Pound, it is only to be expected that Liberty Lobby publications would feature texts on the canonical modernist as a free-speech ‘martyr’ and purveyor of unpalatable ‘truths’ about putative Jewish control. In fact, The Barnes Review dedicated a special issue to Pound in July 1995. Following that issue three years later was an overview in the same journal by Michael Collins Piper, entitled “What Did Ezra Pound Really Say?” – representing little more than a defence of Pound’s conspiracy theories, fascism and vituperative anti-Semitism. Piper’s essay was widely re-published – including from Carto’s Historical Review Press, an arm of The Institute for Historical Review – while the themes remained central to Collins Piper’s anti-Semitic oeuvre. His 2009 study, The New Babylon, Those Who Reign Supreme, was naturally published via Willis Carto, with whom he has “worked closely with” for “over twenty-five years” as “the public face of Liberty Lobby” (Michael, Michael Collins 61-78). Other tellingly titled texts include The Rothschild Empire: The Modern-Day Pharisees, and the Historical, Religious, and Economic Origins of the New World Order. In particular, the latter potboiler basks in Poundian anti-Semitic conspiracies, as made clear by the book’s inside cover:

Examining the New World Order's religious and philosophical roots in the Jewish book of laws known as the Talmud, a product of ancient Babylon, Piper explores the manner in which followers of the Talmud rose to titanic heights in the arena of finance, culminating in the establishment of the Rothschild Empire as the premiere force in the affairs of our planet. Today, with the Rothschild power network firmly entrenched in American soil, the United States today has emerged as “The New Babylon” from which these modern-day Pharisees are working to set in place a global hegemon: The New World Order (Collins Piper, New Babylon summary).

In addition to Jewish control of world financial markets, other writings by Collins Piper allege that Israel was behind the assassination of John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr., as well as having foreknowledge of the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001. Indeed, such is his antipathy to Jews that Collins Piper has attempted to forge an alliance with Middle Eastern anti-Semites. Further highlighting the way in which anti-Semitic conspiracy theories increasingly transcend borders, and even cultures – often in an updated and repackaged form – Collins Piper spoke at a notorious Holocaust ‘revisionist’ conference hosted by Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in December 2006. That same year, ironically enough, Collins Piper launched a radio talk show entitled “The Piper Report”. One of his first guests, naturally enough, was “his friend of some 25 years, Eustace Mullins”. On that programme, in turn, Mullins reflected on his

long-time friendship with famed poet Ezra Pound who was illegally detained in a mental institution in Washington, DC for many years on trumped-up suspicion of "treason" for having dared to criticize the war policies of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. It was Pound who first directed Mullins into research into the Federal Reserve racket and things have never been the same since. There is hardly anything of serious consequence written on the subject of the Federal Reserve today that does not owe its debt to the original research by Mullins, acting under the advice and direction of his friend Pound (Collins and Mullins, The Talk Show).

By the early 2000s, another friend of Mullins, his one-time roommate from the 1950s, Matthias Koehl, had gone further than any of the above with respect to white supremacism. Under the tagline “BUILDING A BETTER WORLD FOR FUTURE ARYAN GENERATIONS”, Koehl had literally turned National Socialism into a fully-fledged religion. In doing so, Koehl placed a quote from the extreme right occultist, Savitri Devi on the homepage of his website, New Order (with the ‘O’ in Order tellingly encircling a swastika):

National Socialism is infinitely more than a mere political creed; the fact is that it is a way of life, a faith in the fullest sense of the word – one could say a religion, however different it may at first appear, from every existing system thus labelled in current speech. Religions are not as easy to uproot as mere political creeds.

The movement’s neo-Nazi aims are set out opposite Devi’s quotation, under a paragraph entitled “The Alternative” – representing an exemplary expression of fascist ideology, as understood by contemporary scholars on the subject.[22]

Today we live under an Old Order. It is a sick, degenerate system of rat-race materialism, self-fixation, drugs, pollution, miscegenation, filth, chaos, corruption and insanity. It is a way of alienation—and Death. But there is a better way, a way of Life. That way calls for a rebirth of racial idealism and reverence for the eternal laws of Nature. It involves a new awareness, a new faith, a new way of life – a New Order. If you would like to find out more about a great historic movement of white men and women working to build a better future, contact us today (Koehl).[23]

Koehl’s support for National Socialist ideas – to the point of venerating them as a religious faith – had developed over more than half a century. In fact, it seems that his overt embrace of neo-Nazism began to develop in the 1950s, when he was the roommate of none other than Eustace Mullins. As might be expected, Koehl was brought by Mullins to St Elizabeths in order to meet his mentor, Ezra Pound. At the very least, this surely did not hinder Koehl’s subsequent advocacy for his longed for “Fourth Reich”. By the 1960s he had gravitated toward the US branch of the World Union of National Socialists (WUNS), the American Nazi Party, rising to the rank of second-in-command under infamous neo-Nazi George Lincoln Rockwell. Following the latter’s murder in 1967 at the hands of disaffected follower, Koehl became the movement’s commander and editor of the movement’s journal, National Socialist World.

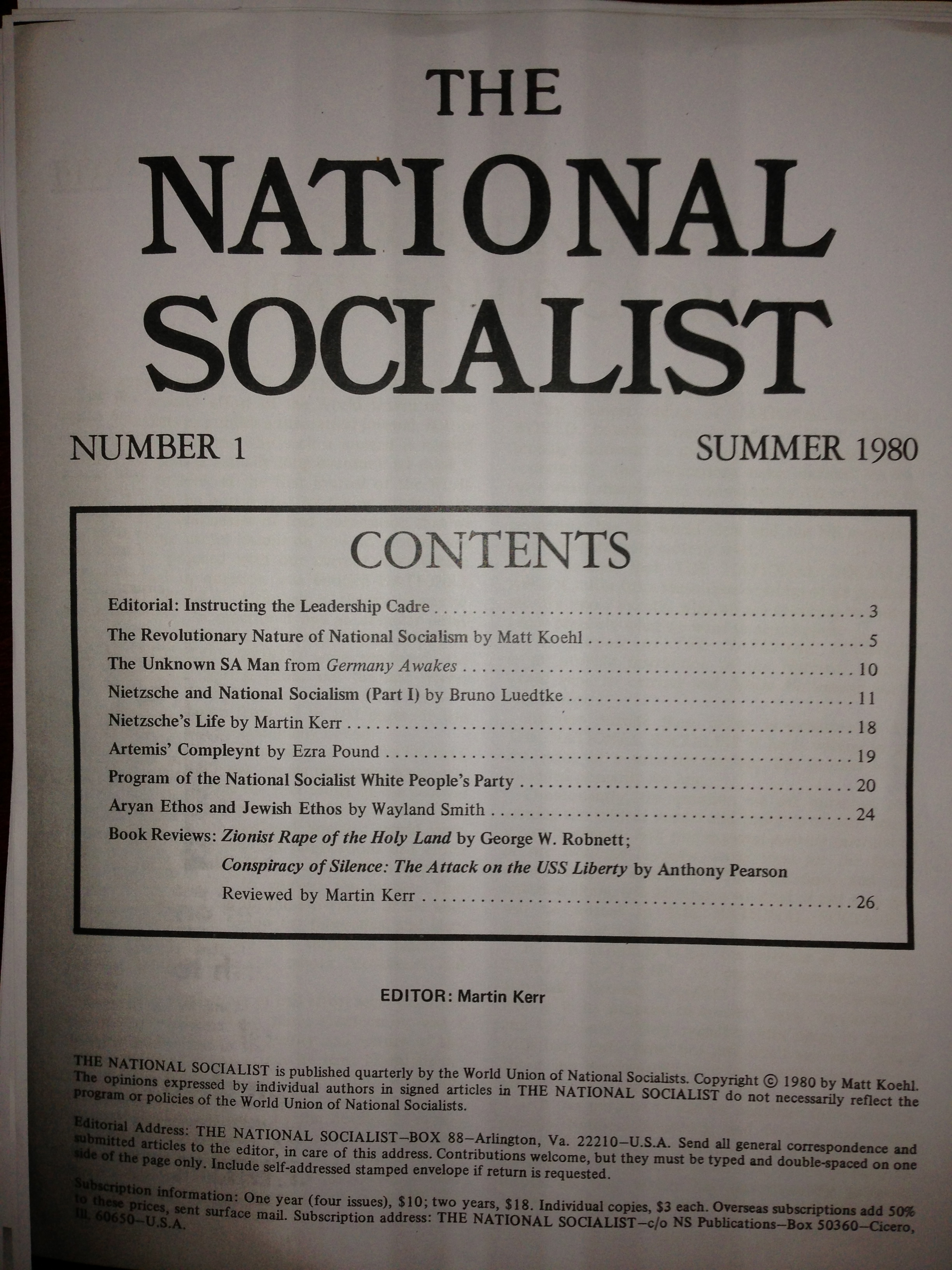

From there, Koehl attempted to add intellectual discourse to the movement in the 1970s, implied through changing the organisation’s name to the National Socialist White People’s Party. Such were Koehl’s attempts to raise the level of discourse amongst the US neo-Nazis that, by summer 1980, he had re-launched the movement’s neo-Nazi publication. Amongst the articles in the journal’s second iteration, The National Socialist, was an article by Koehl entitled “The Revolutionary Nature of National Socialism”, and another anonymous text, “Program of the National Socialist White People’s Party”. Most strikingly, the preceding text was titled “Artemis’ Compleynt”– a republication of the first quarter of Canto XXX by Ezra Pound. It remains an astonishing admission of Pound’s influence upon American neo-Nazi discourse (see image[24]).

Indeed, as exemplified both by the journal’s unabashedly neo-Nazi title – no less than by the movement’s second in command, the British neo-Nazi Colin Jordan – to this day WUNS continues to tout an international extreme right activism based, above all, upon the mythic “Aryan” race. An individual or small group need only therefore self-identify as a “White-Aryan” dedicated to the cause of a revolutionary rebirth in order to join WUNS: no membership cards, political meetings or codes of conduct are needed. As born out by the ‘Participating Members’ webpage of the recently-reformed National Social Movement – naturally headquartered in the United States since its September 2006 re-launch – affiliated countries range from Spain to Serbia in Europe to Mexico, Costa Rica and beyond; there is even, apparently, an affiliated group called the Naska Party in Iran.[25]

Albeit far less overt, another insightful snapshot of Pound transnational influence upon today’s extreme right can be seen in the burgeoning New Right in Britain, the US and elsewhere. Deriving from the French-led Nouvelle Droite launched by Alain de Benoist in the late 1960s, in Roger Griffin’s summation, these avowedly metapolitical advocates of an “Indo-European” have been

a major factor in the overhaul of intellectual fascism since the 1970s. By concentrating on the primacy of ‘cultural’ over ‘political hegemony’ (perversely enough, the New Right draws upon the theories of the Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci), and by stressing a pan-European philosophy of contemporary history, this current of palingenetic ultra-nationalism enables modern fascists to dissociate themselves from the narrower nationalisms of the interwar movements. Their common denominator is that they are all in one way or another linked to anti-reductionism, anti-materialism, and anti-egalitarianism, but free of links with Fascism or Nazism in the public mind (Griffin, Fascist Century 166).

Yet explicitly culturalist attempts to distance the New Right from the unreconstructed, overtly fascist Old Right have been rumbled by the work of Griffin, and even more so, the brilliant historical research of Pierre-André Taguieff, who reminds readers of the Nouvelle Droite’s repackaged prejudice – now going by the fancy-sounding term ‘ethno-differentialism’ –

Neither “fascism” nor “racism” will do us the favor of returning in such a way that we can recognize them easily. If vigilance was only a game of recognizing something already well-known, then it would only be a question of remembering. Vigilance would be reduced to a social game using reminiscence and identification by recognition, a consoling illusion of an immobile history peopled with events which accord with our expectations or our fears. Magical vigilance: one declares oneself “vigilant” to prevent the return of the “old devils.” If vigilance was only a game of recognising something already well-known, then it would only be a question of remembering (Taguieff, Discussions 54).[26]

This injunction certainly applies to New Right iterations in the US and Britain, both drawing heavily upon Ezra Pound’s post-war legacy. In the US, Greg Johnson’s online outlet for the North American New Right, Counter-Currents Publishing, has made heavy use of Pound’s writings over the last few years, including the 1939 standalone BUF pamphlet on 28 October 2011, What is Money For?; the 1935 Social Credit: An Impact on 30 October 2012; and, in five parts, the 1933 ABC of Economics in December 2012. More recently, Johnson has continued lauding Pound’s writing, posting some of his early poetry on January 27 and October 30, 2013; a video containing Pound’s reading of Canto I on February 28, 2013; and then, in five parts, reposting the entirety of Pound’s 1933 screed, Jefferson and/or Mussolini – which commenced Pound’s interwar activism for fascism in Italy and Britain[27] – between 28 October and 1 November. It seems these autumn dates were specifically chosen, as Johnson maintains, to coincide with Pound’s birth- and death-days:

The end of October is one of my favorite times of the year, and not just because Halloween falls on the 31st. On the 30th, we celebrate the birthday of Ezra Pound, poet and prophet of a just social and economic system, and on November 1st, we commemorate his death.[28]

John Drummond’s translation of Pound’s 1944 text, Oro e Lavoro, explicitly written for the Nazi-occupied Salò Republic, is the most recent of Pound’s writings to be uploaded on Johnson’s Counter Currents site – with thanks to “Kerry Bolton for making a copy available for scanning.”[29] Even in the transnational arena of metapolitical activism, it seems – especially with the rise of online connectivity in the last generation – the world remains a very small place for extreme right ideologues. To be sure, this internationalisation of New Right celebration of Pound’s poetic and political writings bears out Frederico Finchelstein’s recent claim that, “[i]n order to grasp the global and transnational dimensions of fascism it is, however, necessary to understand its history, first in its national articulation and second to relate this manifestation of fascism to intellectual exchanges across the Atlantic Ocean and beyond” (Finchelstein 321).

This “beyond” doubtless embraces Britain’s New Right as well, launched through the aegis of long-time extreme right activist Troy Southgate – once of Britain’s avowedly neo-Nazi National Front in the 1970s; the International Third Position in the late 1980s (in collaboration with Nick Griffin, current leader of the neo-fascist British National Party; BNP), and a pioneer of ‘metapolitical fascist’, or apoliteic, music (Shekhovtsov, European Far-Right Music 279). [30] Southgate launched Britain’s New Right in January 2005, with the recently-deceased Jonathan Bowden the guest speaker. Testifying to the intimate connections between the ‘metapolitical’ New Right and the revolutionary Old Right, Bowden was intimately connected to Griffin’s BNP at the time, rising to the role of Cultural Officer and Advisory Council Member in 2007. In an interview with Southgate in 2010, published under the revealing title “Revolutionary Conservative”, Bowden advocates “the mixing together of ultra-conservative and neo-fascist ideas; second, a belief in the importance of meta-politics or cultural struggle.” It is this “creative vortex” that Bowden understands as the extreme right attempt “to back past verities in new guises”; moreover, “the New Right recognises that fascism and national socialism were populist or mass expressions of revolutionary conservative doctrines.”[31]

For Bowden’s part, this more culturally inflected extreme right activist had long counted Pound as one of his political idols; for example, he is cited twice in the aforementioned 2010 interview with Southgate. Bowden is yet more explicit about the role of Pound in British New Right thinking in another interview with a ‘metapolitical’ activist, the Croatian ideologue Tomislav Sunić:

I agree with Ezra Pound that the artistic community is like the antennae of the civilization that they’re a part of and that they feel the tremors in the web or in the ether before anyone else [….] It’s interesting to note, in relation to modernism for example, many of the early modernists—Eliot, Wyndham Lewis, Marinetti, Céline, Ezra Pound, and so on—were deeply attracted to the extreme Right. They were attracted because they saw in it fundamentalist cultural energies.[32]

Given the international linkages amongst the contemporary extreme right – above all, exemplified by the Euro-American New Right – it should come as no surprise that Sunić’s interview with Bowden is available on Greg Johnson’s North American New Right website, Counter-Currents Publishing (where, alongside Kerry Bolton, Bowden is listed as one of “Our Authors”). So too is the pièce de résistance of Bowden’s Poundian interest: an hour-long hagiography on the American modernist at the 33rd meeting of Troy Southgate’s London New Right on 11 June 2011 – some nine months before the latter’s death. In fact, the entire text is available to audit on Counter-Currents Radio.[33] Perhaps by way of tribute, Southgate’s publishing outlet, Black Front Press, published an edited collection on Pound in 2012 entitled Ezra Pound: Thoughts and Perspectives, Volume Six. Again highlighting the transnational nature of Pound’s influence, contributors included Southgate and Mariella Shearer from the UK; Dimitris Michalopoulos from Greece; alongside republished articles from the Australian Kerry Bolton and the American Michael Collins Piper. Were there any question about the international and ideological bona fides of this volume and its parent series, additional editions in Southgate’s Thoughts and Perspectives collection include Jonathan Bowden (Volume 9); the Italian Fascist and key post-war extreme right ideologue Julius Evola (Volume 1); Corneliu Codreanu, leader of the interwar Romanian Iron Guard (Volume 5); the German “Conservative Revolutionary” Ernst Jünger (Volume 11); and, with a Poundian ring, even the extreme right author from Japan, Yukio Mishima (Volume 8). Likewise the National-anarchists, headed by Southgate since the 1990’s, claim an influence from Pound – emphasised in the website’s Italian version – in a page dedicated to economics, where the group closely mirror’s Pound’s programme.[34]

Pound and Post-war Italy: “Fascists of the Third Millennium”

Considering the importance of Pound’s case to white nationalism in the US, it should come as no surprise that his influence was also felt by the far-right across the Atlantic. As noted above, this has been the case, above all, with CasaPound in contemporary Italy. CasaPound Italia, to give the movement its full name (often abbreviated as CPI), is a recent association that has its roots in the hardrock band Zetazeroalfa, born in 1997 and headed by Gianluca Iannone, later the founder and head of CPI. CPI’s activists, sometimes referred to as a santa teppa [holy mob] – reflected in the text of a Zetazeroalfa’s song – unabashedly declare themselves to be fascists, despite the fact that longstanding Italian laws prohibit the formation of explicitly fascist parties. Similarly, the band ‘270bis’, provocatively named after the article of the Italian penal code that punishes subversive associations, often airs on Radio Bandiera Nera [Black Flag Radio] CPI’s online broadcasting arm; their song Bomber nero [black bomber jacket], claims they are youths who “love Hitler and Mussolini’”and yell “Sieg Heil outstretching their arms.”[35]

The movement’s unofficial birth occurred on 12 July 2002, when a group of well-known far-right activists occupied a public building that had been empty for several years. This type of squatting in Italy is generally regarded as anarchist or communist, and has long been the preserve of radical left wing groups. The occupied building in Rome was renamed CasaMontag – after Guy Montag, protagonist of Ray Bradbury’s science fiction novel Fahrenheit 451 – first giving rise to what were called ONCs [Occupazioni Non Conformi, or Non-conformist occupations]. On 26 December 2003, the same group occupied a building on Via Napoleone Rome and renamed it CasaPound Italia; since then, CPI has been a growing force in both Italian, and especially in Roman, politics.[36]

The introduction of CPI’s political programme declares:

The Italian nation must again become a living organism with tasks, life and means superior, for strength and power, to that of individuals […] it must to be a moral, political and economical unity that is integrally realised within the State. The State we want is an ethical, organic, inclusive […] state. […] A social and national Italy, according to the vision of the Risorgimento, of Mazzini, Corridoni, the Futurism, D’Annunzio, Gentile, Pavolini and Mussolini (1).

Given his overt valorisation of Mussolini, Iannone is among those to have recently created an honour guard standing continuously outside Mussolini’s tomb in his birthplace, the small town of Predappio. As Iannone declared in an interview from late 2011:

CasaPound is based around four principles: culture, solidarity, sport and (obviously) politics. These four domains can be seen as social actions in one way or another. CPI organises book presentations, plays, concerts, debates about movies and has a monthly publication (Occidentale) [….] We try to communicate in a radical mode and renew our dream. We want to launch it and give it a new spin. It could be through music or art.

In terms of the movement’s namesake, Iannone had this to say:

Ezra Pound was a poet, an economist and an artist. Ezra Pound was a revolutionary and a fascist. Ezra Pound had to suffer for his ideas, he was sent to jail for ten years to make him stop speaking. We see in Ezra Pound a free man that paid for his ideas; he is a symbol of the “democratic views” of the winners.[37]

That CPI’s socio-political project explicitly refers to key tenets of fascist ideology. This is evident in any number statements by leaders of the movement, such as from the online broadcaster for CasaPound’s Black Banner Radio:

We are an organisation of social advancement that aims to use the power of volunteering to defend its social visions’ [….] ‘What we love of fascism is the attention to justice, the great social and administrative achievements in the interest of the entire national community,’ Cristiano Coccanari declares, ‘and the work done to render Italy a destined community from the Alps to Sicily, and not a mere geographic expression’.[38]

Similarly, in The Guardian’s columnist Tom Kingston’s view, CasaPound's approach to economics is pure Mussolini, “we would like to see communications, transport, energy and health renationalised and the state constructing houses which it then sells at cost to families,” said Simone Di Stefano, CPI’s vice president and candidate for mayor of Rome in the elections of 2013. On immigration, the stance is typical of the far right, “we want to stop it,” says Di Stefano: “Low-cost immigrant workers mean Italians are unable to negotiate wages, while the immigrants are exploited.”[39]

Equally, in their online “Ideodromo” – described by Iannone as “the place where our ideas take form" – CasaPound’s spokesperson, Adriano Scianca, claims that the main reason for CPI taking the North American poet as their main example is “because Pound was fascist”. In facts, these self-proclaimed “fascists of the third millennium” look to Pound as a model for contemporary applications of fascist ideology. This owes much, in turn, to Pound’s conception of fascism as a “third way” to both liberal democracy and socialism. Correspondingly, Scianca is surely right in saying that Pound’s writings on radical economics appear prophetic for many contemporary readers on the far-right. A fitting example can be found in what Pound wrote in his 1944 Italian essay Lavoro e Usura [Work and Usury]:

The banks’ pitfall has always followed the same road: an abundance of any kind is used for creating optimism. This optimism is exaggerated, usually with the help of propaganda. Sales increase. Prices of lands, or shares, go beyond the scope of the material rent. Banks that have favoured inflated loans to drive to the rise of the prices, suddenly restrict and recall the loans and the panic occurs (Pound, Lavoro 106-107).

While the above characterisations on Pound’s political propaganda are still contentious – albeit uncontested by CPI itself – a consistent attempt has been made to play down Ezra Pound’s own racism and, especially, his virulent anti-Semitism. In the words of Scianca: “It's important to remember that he renounced anti-Semitism, but never fascism".[40] In turn, this disavowal of anti-Semitism is in keeping with a longstanding attempt by extreme right protégés of Pound to distance their mentor from his visceral radio attacks on Jews during WWII. Thus, in an interview with Alexander Baron from 1993, Eustace Mullins asserted “he [Pound] wasn’t an anti-Semite, and neither am I myself!”[41]

Finally, the most recent book-length account from CasaPound, Ezra fa surf: Come e perché il pensiero di Pound salverà il mondo [Ezra surfs: How and why Pound’s thought will save the world] was written by the aforementioned Adriano Scianca, who has been responsible for the cultural section of CasaPound since 2008. The short outline of the book, on the editor’s website, proclaims:

A rocker Ezra Pound who will save the world? His thought, even if it belongs to the past century, appears as extremely timely [.…] A Pound who is philosopher and economist that can be considered a master of ethical anti-conformism for such personalities as Bukowski, Allen Ginsberg and Pasolini, […] Patti Smith and the Velvet Underground […] carrier of a message of dialogue which is typically Mediterranean, anti-chauvinist, and against any xenophobia and prejudice.[42]

Ezra surfs was released on 19 September 2013, and in an interview the author declared that the title refers to William Kilgore’s phrase from Apocalypse Now, “Charlie don’t surf!” (‘Charlie’ was the derogatory term for the Vietcong used by American forces in South Vietnam.) For Kilgore, “Charlie” is not cool because he doesn’t surf. In the film, Kilgore is the “classic obtuse Yankee,” convinced that US forces would win the war in Vietnam because Charlie is a “loser”. In turn, Sciacca views him as a kind of anti-Pound, as the lieutenant colonel is a close-minded militarist - whereas the poet criticises the usurious “war system”. For Sciacca, “Pound surfs because he is more fresh, free, original, revolutionary of all today’s fashionable scribblers.”[43] The idea of Pound surfing, like the reference to Bradbury’s Casa Montag, further underscores with willingness of CasaPound to borrow cultural references from the across the Atlantic. Here too, a strictly national understanding of these self-proclaimed “fascists of the third millennium” can miss the transnational wood for the more parochial trees.

Furthermore, Sciacca argues that the contemporary world expresses itself through recourse to slang references to the sea, such as the “navigation” on the internet; thus “to surf on the present condition has somehow the same sense of Julius Evola’s Riding the Tiger, which means being within modernity, but fighting for a different modernity.” This “surfer” Pound is also the inspiration for CPI’s approach to the issue of immigration. Contained in the “Ideodromo” is a section titled Perché ci piace Ezra Pound [Why we like Ezra Pound], where Sciacca states that:

In a world that piles up disorderly languages and cultures, devouring human flesh and covering up this genocide behind facades of nice and colourful babble, Pound has shown the way for a sane cosmopolitanism, one that pays attention to differences but without forgetting one’s roots.[44]

Yet Pound’s anti-Semitism was long based on the supposed propensity of Jews themselves as exclusive, exclusionary and rejecting cultural diversity. As Pound said in his 1935 article “Germany Now” in The New English Weekly, “the idea of a chosen race is thoroughly semitic.”[45] This gave the right to Pound, and today to the CPI’s activists, to defend “Roman sanity” from alien influences, “for developing the real differences, beyond the multi-racist society”, as expressed in CPI’s political programme remarkably called Una Nazione [One Nation]. This programme (cf. point 3) evokes various far right measures for the control of immigration, and for defending Italian society from supposedly intolerant cultures, extending to the suspension of the Schengen Treaty (allowing free movement of citizens within Europe) and the repatriation of illegal immigrants (3-4). As examined by Pierre-André Taguieff and other scholars working on the contemporary extreme right, this discourse may be seen as a kind of upside down racism, and is most prominently associated with the Nouvelle Droite’s chief ‘metapolitical’ ideologue, Alain de Benoist.[46] Thus, the assumed racism of multicultural “race-mixing”, justifies policies familiar from last century: segregation of different ethnic groups, and repatriation where possible.[47]

Pietrangelo Buttafuoco, a notable journalist and writer who worked for a number of different Italian newspapers (La Repubblica, Il Giornale, Il Foglio Quotidiano), magazines (Panorama) and television stations (LA7 and Berlusconi’s Canale 5), wrote the preface of Scianca’s Pound surfs. Pietrangelo is the son of Antonio Buttafuoco, a former deputy in the ‘post-fascist’ Movimento Sociale Italiano (MSI, or Italian Social Movement), and a member of the central committee of the party.[48] As emphasised in Buttafuoco’s preface, the book recounts aspects of Pound’s economic and social vision, since he demonstrated that the only alternative to the uncontrolled dominance of the “market” is not “democracy” but the “temple”:

The biggest insult that democracy has committed against Ezra Pound is not having locked him in “the gorilla cage”. Nor, by itself, the fact of having thrown him in the ‘hell hole’ of St. Elizabeth's for thirteen years. The real bleeding shame of Pound’s case, instead, is the power of violence by the enemy of beauty and goodness.[49]

Pietrangelo Buttafuoco thus writes on behalf of a very different ‘face’ of the post-war far-right than that of Eustace Mullins, Willis Carto or even his father, yet he likewise finds in Ezra Pound’s outlook direct inspiration, even a future direction. In underscoring this point in his revealing preface, Buttafuoco then cites a verse of Canto XCVII, from the sequence Thrones de los Cantares where Pound reaffirms his beliefs in the continued religiosity of the west no less than those on usury: “the temple is holy because it is not for sale”.[50] This is in order to assert, characteristically – if rather more opaquely than in past – that the “perfect revolution is the one that doesn’t chatter about rights, but evokes gods”:

There is no solution outside the temple. Because religion is man’s basic instinct of survival. Religiosity is the key. And, likewise, there is no revolution without Pound. […] against the queen of mystifications, that macabre dance of the fight between civilisations, consciously organized by those with an interest in perpetuating wars. That is a system that creates wars serially, as the poet shouted, without being heard, from the microphones of Radio Roma.[51]

While but scratching the surface, this article has shown that Pound’s influence amongst extreme right ideologues is equally transnational and persevering. Of the former, activists from New Zealand to Italy, and Britain to the United States, testify to his continuing relevance in – at least – three ‘faces’ of the contemporary extreme right: white supremacism, neo-fascism, and New Right ‘metapolitics’. In each, he is lauded as a political martyr and cultural icon. Of the latter, the continued relevance of Pound’s fascist legacy is such that, from the present perspective, it is unlikely to be circumvented anytime soon. Despite what his many poetic admirers and academic analysts may wish to be the case, it is clear that Pound’s memory is alive and kicking on the extreme right. This may be so much the case that what his fellow Anglophone poet, Basil Bunting, had to say of his modernist writing may also be true of his revolutionary right-wing politics:

There are the Alps. What is there to say about them?

They don't make sense [….]

There they are, you will have to go a long way round

if you want to avoid them.

It takes some getting used to. There are the Alps,

fools! Sit down and wait for them to crumble![52]