Late Capitalism and the Problem of Individual Agency: A Reading of the Poems of J. H. Prynne

Rupsa Banerjee

Interpretative geography and the practice of the aesthetic share a relation that throws new light upon the interaction between the individual and the state thereby informing our understanding of the nation. The nation located through such a practice becomes an entity that is tempered by the functioning of individual affects[1] and at the same time homogenized to fit into cartographic demarcations. To a large extent, the indeterminate category of geography (owing to the conurbation of spaces, the dense array of spatial artefacts and the telescoping of the self from the city onto the nation) can be refracted across two levels of meaning-making – the upper limit of ‘space’ and the lower limit of ‘place’. The limit of space emerges as a palimpsest containing within itself the medieval imagination of the infinite, the eighteenth century constructions of the Absolute (joining point, position, place, region) while being contained within the cognitive capacity of the finite human subject. On the other hand, the lower limit of ‘place’ understood geographically as ‘locale’ or ‘abode’ becomes the means of understanding the individual’s subjectivity placed within spatial boundaries. The conceptual boundaries of space and place are instrumental for understanding the manner in which resistance against late capitalist ways of being is formulated within the purlieus of the city and is then transposed onto that of an abstract entity such as the nation. J. H. Prynne’s poems look at the state as a transformative category and delve into the processes of commoditization that creates the generic structures of nation, state and critically assess the ways in which such structures are reproduced and sustained.

Within the ambits of literature, geography has always played an integral part in formulating a sense of national identity. In late seventeenth century England, for example, John Bunyan’sThe Holy War – The Losing and Taking Again of the Town of Man-soul (1682) disputes over the territory of the town which then becomes an allegory for the disputes over national sovereignty (following the collapse of the English Revolution and the establishment of the Restoration period). Closer to our time, the poetry of W. B. Yeats strives to create an Irish national literature which distinctly conveys a sense of the Irish national soil. However, following from the late capitalist defenestration[2] of actual boundaries, we find that the notion of community and the contextualization of a community of people become increasingly difficult as there is a whole range of geo-political phenomena that come to define the function of the individual. The dialogue between the poets Wallace Stevens and William Carlos Williams through the means of poetry addresses this very issue (Stevens had written the poem “Description Without Place” in 1945 and to which Williams responded with his “A Place (Any Place) to Transcend All Places”). Philosophy thus intermittently skirts the relation between the material nature of political identity and the nation that gives birth to it. And we see, the subjective experience of space remains one of the pivotal themes in literature as well, capturing the vagaries of a subjectivity caught in the twilight region of experiencing and exploiting.

In my article, I will look at two poems of J.H. Prynne, a Cambridge poet whose first works appeared in England in the 1960s but whose publication of Poems by Bloodaxe Books in 1982 marked the beginning of a worldwide interest and enquiry. The poems “The Numbers” and “Die A Millionaire” appearing in Kitchen Poems (1968) tap into the ways in which literature makes it possible to understand the nuances of an individual being at once a visceral part of an abstracted nation while at the same time being girdled by a place-driven, community-centric living within the boundaries of a city. The symbolic identification of the individual with the nation is maintained not merely through noetic means but “has to be coupled with an affective investment grounded in the body for national identity to emerge” (Stavrakakis 200). Formation of national identity is thus not merely dependent upon “the structural position of the nation as a nodal point” (Stavrakakis 200) but takes place through ways in which the individual locates himself within the nation-space, whether it be through the ritualization of practices such as elections, consumption methods, capitalist trade innovations’ sojourn into the self (all of which come to be detailed in Prynne’s poems).

Husserl’s speculations of empathy and a common objective Life-world serves as an important ground from which to mark the postmodern predilection for the commonality of experience and the distension of scientific knowledge into our common, quotidian, every-day understanding of the world (an understanding that is very important for poets like J.H. Prynne). Husserl had attempted, starting from the second part of his book Formal and Transcendental Logic, to search for a “usually un-thematized basic level of experience that is independent from cultural and historical facts” (Langsdorf, Vatson, and Bower 18). This “basic level of experience” is what he calls as Grundschicht.[3] The Grundschicht which appears as the “enworlding of the environing world” has a special connection with the lived body. As Adam Konopka states in his The Environed Body:

The manifestation of the unthematic environing world does not occur as a part or piece of objective space, considered as a homogeneous spread of univocal locations. Rather, an environing world is a place occurring as a bounded unthematic horizon determined in correlation with the lived body’s absolute here. (Konopka 293)

The “lived body’s absolute here” performs an important function in orienting the individual’s position in the space of a democratic institution such as the nation. The nation no longer remains an abstract category as it materializes through the functioning of individuals within it. My analysis of Prynne’s “The Numbers” and “Die a Millionaire” will look at the ways in which the individual is located in the state. The first poem seeks to show the ways in which individuals identify and at the same time differentiate themselves from other individuals in the state. The body functions here, as Prynne shows, to make tactile experiences like walking[4] the basis for understanding our means of becoming within the category of the nation. The other poem will look at the ways in which the interests of individuals as a collective are plotted onto the body of the nation. This kind of an ontological understanding of the state prevents us from viewing the state as “fixating and monopolizing political activity” (Melançon 9). Instead it allows us to broach the possibility of the existence of such a state that is a product of dynamic political action where its past and present actively engage with each other and where the “possibility that it might be continued, taken up, de-formed and re-formed, and eventually overthrown into new institutions” (Melançon 9) remains well accounted for. The state as it emerges in the understanding of Prynne’s poems can then draw a corollary with Merleau-Ponty’s idea of an institution:

[an] establishment in an experience (or in a constructed apparatus) of dimensions (in the general, Cartesian meaning of system of reference) in relation to which all a series of other experiences will have meaning and will make a sequel, a history. (Merleau-Ponty 38)

Prynne’s poetics instantiates a coherent ligature between such thought and the aesthetics of his writing. In the poem, “The Numbers,” Prynne develops a writing that creatively binds together the problem of representation addressing the dissuading non-coincidence between the geographic entity of the nation-state represented by maps and the entity known through our private experience. The poem’s language removes the subject from the complacency of geographical and economic facts (scaffolded by the ever-proliferating numbers) and helps him formulate an understanding of himself by historicizing and spatializing the familiar relationships between the individual and the world.

Conflated around Prynne’s poem are secondary and tertiary theorizations about space but at the very fundamental limit of such thought Prynne contrives to build a philosophy that is phenomenological in its proclivity towards making individual identity invariably re-locatable to the body. The shrinking of the threshold of intelligibility from the ever expansive apertures of sense assimilations of the physical body augurs the pattern of sense making in the late capitalist world of the poet. “To shrink the confines down” in “The Numbers” foregrounds the basic tenet through which to articulate the perspective of the Late Modern British subject:

[…] to shrink the confines

down. To signals, so that I come

back to this, […] (Prynne 10)

In the case of Prynne, it is the subject’s own shrinking down of the powers of cognition that forms the underlying substratum for the commonality of experience. It is important for us to remember here that Frederic Jameson in The Cultural Turn states that the individual’s orientation in space becomes the predominant factor that helps him understand his relation to the architectural changes in the cityscape and thus moulds his identity as a citizen.[5] Prynne in his poem refers to the possibility of shrinking the ‘confines’ of such affective bonds between the individual and the state and thus allows for a more effective way of understanding late capitalist subjectivity.

The dualistic understanding of space and place necessarily feeds into the understanding of the land as it shifts from the binaries of “present-at-hand” (an immanent, undifferentiated entity) to “ready-to-hand”[6](where land is an integral part of capitalistic production regime where existence is measured in terms of production). Space as humanly prior and place as experientially constituted are brought together in the narrative of democracy. The coming into being of the nation-state is integrally connected to the identification of land as personal property. One can find an allegorical connection between the exaltation of Absolute, homogeneous ‘space’ over that of individualized, experiential ‘place’ in the introduction of the Land Enclosures Act (1750-1880) in England. The understanding of space as separate from the body of man (as theorized by Newton in his Principia) came to form the rational theoretical premise which aided in the conceptual passing of the Enclosures Acts. The place-centric dimensions of national identity that had prevailed before the passing of the Act now were completely made obsequious to the grandiose imagining of an abstracted ‘national’ state. Ellen Rosenman writes in her article:

Villagers had a sense of identity rooted in a specific area and embedded in a web of familial and neighbourly relations that had defined that place through generations. This association between identity and place is so intuitive, so prevalent in western culture that geographer Tim Cresswell terms it a “metaphysic.” With wage labour came enforced mobility as workers were compelled to travel to different villages, towns, and cities to eke out a living. The imbrication of “the people” and “the land” underlay the trauma of the Enclosure Acts, giving rise to a narrative of not only economic loss but dispossession in which farmers saw themselves as refugees in their own land. (Rosenman, “On Enclosure Acts and the Commons”)

The understanding of landscape was therefore grounded on the larger understanding of ‘space.’ In The Dark Side of Landscape (1980), John Barrell details the way in which landscape was depicted in paintings made between 1730 to 1840. Barrell sees English landscape as essentially an ideological expression where the rural of the land were depicted as “[...] capable of being, as happy as the swains of Arcadia” (qtd. in Adams and Robins, 6). This indeed is a way of the aesthetic to reconcile the existing differences existing in reality through the imaginative act of symbolic creation. Literary examples of a similar hurt registered by the government possession of land can also be found in the works of the Romantic poets such as Williams Wordsworth in “The Ruined Cottage” and Oliver Goldsmith’s “The Deserted Village.”

Within the precincts of the twentieth-century, we find Prynne articulating a similar need to stress upon the material nature of an individual’s existence and ground the political action of electing one’s government onto the physiological processes of the body which are invariably intimately connected with the land that one inhabits. The role of the body in this poem is to help see place as embodied. The body is the “missing "third thing" between a sensible something and its particular somewhere” (Casey 204-205). Prynne’s focus on the body and the subjective apprehension of space makes it possible to think of the nation-state outside of the traditional markers of false-consciousness and affectively locates the question of politics in the question of the skin. The instance of the body’s bi-laterality in Kant as a critical means of understanding the orientation of things in space becomes even more clear in the second poem with regard to the “twist-point.” While Jameson talks of the waning of affect and the body’s inability to make sense of the city (discussed earlier), Prynne makes the question of politics a question of affects (bodily movements recurrent throughout the poem). Although multinational capital enters into previously uninhabited territories reducing the sense-constituting depth-model of cultural products (see end-note) into a play of surfaces Prynne’s poetry constantly attacks the seeming monolithic sameness of the surfaces, whether it be the surface of textual meaning, the surface of land as a marker of national identity. It is in this context that the meaning of the line “Quality as firstly position” becomes apparent.

The late capitalist tendency to override the nature of the affective bonds that connect the understanding of the land with that of community is arguably seen to be countered in the poetry of J. H. Prynne. In the age of globalization, where there are several discourses that emplace the individual within the entity of the nation, Prynne’s writing carefully attempts to study the manner in which the individual identity can be precipitated. The modern day terminologies of ‘politics’ and ‘ethics’ that are integral to the constitution of the ‘space’ of the ‘nation’ go back to Greek words which inherently signify place: “pol~ and ~thea, ‘city-state’ and ‘habitats’, respectively. The very word ‘society’ stems from socius, signifying ‘sharing’-and sharing is done in a common place” (Casey xiv). In the twentieth century where the ideological standing of ‘place’ has seen a great upheaval in the works of critics (such as Frederic Jameson who sees place as the determining factor of modern subjectivity), it becomes necessary for us to focus on the aesthetic apprehension of place.

Prynne’s poem, “The Numbers,” begins with “The whole thing it is.” The concern with the whole invariably connects the concern about postmodern excess with that of the modernist model maintaining (or appearing to maintain) stringent distinctions between quantity and quality. J. H. Prynne’s poem “Lashed to the Mast” from his 1968 collection, The White Stones, sketches out the issue of the whole and the problematic of perceiving the whole while at the same time retaining a substantive idea of oneself in the lines:

the whole need is a due thing

a light, I

say this in

danger aboard

our dauncing [sic] boat

hope is a stern

purpose

no play save the

final lightness

the needful things are a sacral

convergence, the grove on

the hill we know too much of-

this with no name & place

is us / you, I, the whole other

image

of man (Prynne 49)

The question of the whole invites the question of the role of the individual with regard to the whole of the world and consequently the ability of language to articulate this relationship as well. Peter Riley in his Working Notes on British Pre-History, through his study of the activities of the primitive men (building of monuments as extensions into the landscape) and the burial patterns in the Neolithic age (not having any difference in the burial sites of the common masses and the more privileged) argues that in the Neolithic age there was a continuity between the individual and the world:

It doesn’t make the individual a cog in the machine – a part of a whole. Rather the singular containing the whole as much as the whole the singular, towards a perfect control, harmony. (Riley 236)

Peter Riley’s predilection towards the fact that there is an inherent bond between the individual and the world can be seen in his statement:

I feel all Neolithic properties to be bound in a sense of community which wasn’t at all artificial or merely adequate to the technological needs, but was felt and informs every manifestation of the presence of these men. What, statistically, the Neolithic Community was I don’t know, or whether I should call it Tribe (by ancestry, election or whatever), but it was THERE. That the distinction between one man and the group was by no means a simple matter. So that the group could act as one man, and the things it left behind bear about them the features of having come from the human body. (Riley 236, underlines in the original)

My concern with the late capitalist state thus gains momentum here when arguing the kind of changes in the notion of the community as a result of the differentiation of affective relations between the self and the world for state-coercive reasons. This concern of the relation between the individual and the ‘whole’ of the society that he lives in can definitely be identified as an important concern in Prynne’s writing. Prynne supports the fact that the parochial grammar of language, fossilized as a repetition of repetitions weakens the relationship between the speaker and his place thereby also doing away with an affirmative possibility of a community.

Prynne stresses on the question of language’s complicity in determining the nature of the relationship that an individual shares with ‘place.’ In his article printed in Jacket Magazine, Prynne writes,

The exotic remoteness of that location at once bids to compose an allegory of displacement, which in turn demands a fully prepared resistance. Plants grow in the same way, upwards. People eat lunch, eye each other, words fly out of mouths. Does the subject-position bind to the life-world by a different syntax? Well, these poems and writings set out a composite text of investigation into such imponderables. (Prynne, “Afterword to Twitchell’s Original Chinese Poetry”)

Prynne’s reflection on language and its relation to the Life-World states that the subject as ligatured with the life-world through the grammar of language and rearranging the corollaries of such a system can actually reconstitute the experience of the life-world as well. However, even this statement in the writing of Prynne converges upon his general scepticism regarding what forms the “essence” of a place. He is sceptical of the very processes, which give rise to the modern day conception of space, a specific topological entity, characterized by laws of land ownership. As Riley details,

My instinct is that the distribution of local instances of fact which can be grouped (pot and implement typology, for example) has led to imposed ideas of region that are foreign in pre-literate landscape and which are (by unacknowledged retrojection) based on common-law practice concerning land-ownership. (Riley, 240, underlines in the original)

It is because of this reason Prynne constantly attempts to see the land of the nation-state in a very different way in his poetry. In Post-imperial Britain, after the Suez Canal crisis, and the disowning of several colonies, Prynne’s ontological grounding of being becomes a language that is set at the boundaries of meaning-making and sense constitution. This distancing in terms of the poem’s penchant towards referentiality replicates how the products of capitalism are removed from their direct relation to the production process and become merely a reproduction of the processes of production. It is Jameson’s contention (dealt with in the essay “Postmodernism, or The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism”) that the free movement of multinational capital translates into the realm of artistic creation doing away with the “depth-model” of meaning-making and making it a play of surfaces.[7] Prynne’s poetry, I would argue, does not do away with the task of referring to a world outside of itself as Language poets like Charles Bernstein would have. Resistance to meaning-making connects back to the unreliable nature of surfaces, whether taxonomic or tectonic and help us approach the question of the capital as affectively entwined with the land and community emplaced in it. The discursive practices of Prynne’s language come to mirror the ways in which identification comes to materialize in a capitalist nation whose colonies are fast receding and questions the nature of libidinal investments inherent in national identification.

The play of the ‘I’ and ‘We’ signifiers bring out the manner in which language can contest the obfuscating nature of democratic functions. The poem functions as a mirror unto society but even then the function is performed self-consciously. It presents itself as the author of ideas, the perpetrator of discerning meliorism, subject to the processes of history. Although the poem brings in a free flow of imperatives such as must, want, owe, should, there is a sense that the poem’s actual desire is for registering stimulus and response, the need for movement and seeking rather than generating a bed of comfortable presuppositions about the destination and what one would find there.

If we take the Lacanian idea that the subject is a position in language, then it becomes evident that the whole project of subjectivity lies in the manner in which we can manipulate language. The poem takes into account language’s supreme hold upon the self, where the ‘I’ is no longer indicative of a substantial category but is something that is secondary to the orders of language. There is an attempt at counteracting the vacuous subjectivity of humans, by stressing upon the ‘We.’ This is a move that encapsulates within itself an attempt to institute an absent presence. What the oscillation between the ‘I’ and the ‘we’ signifies in the poem is perhaps the break between the elemental self and the communal self, both of which ascertain the historically contingent nature of human beings.

The split constituted within the poem, between the ‘I’ and the ‘we’ becomes more apparent when we study the context in which they are used. The phrases, ‘I am no more’, ‘I suspect myself’, ‘I must stand off’ insist upon the shrinking back of the individual, derided by doubt and lack of conviction. On the other hand, the ‘we’ is seen as the sole prerogative for action, for example, ‘we must take aim’, ‘we must shrink’, ‘we should conserve’ etc. There is thus a tension grounded in the interrelation between the individual and the collective. The poem appears to disparage any possibility of a consoling shared condition between the individual and the whole. It is because of this reason that we can argue that the poem is not complacent in assuming a humanist position. The poem takes account of the conditions that mark the fertile ground for action.

Modern society is such that the individual is prohibited from asking his ‘national point no more’. On the other hand there is a maddening, overpowering need of the collective to act, to ‘conserve by election’. Although the individual is proclaiming the disparate nature of his political existence, (“it doesn’t concern any of us”), yet he acts, because his actions are endorsed by the fact that he is indebted; (“we owe (in the weak sense [...]”). The open parentheses that the poem introduces here, is perhaps explicative of the contingency of human actions. It is the “firm question of election” that derides our personal existence. The reason why the poet stresses so much on the incommensurable nature of will and action, by subversively projecting the all-encompassing collective will, is perhaps to stress upon the obfuscating rings of ideology. Ideology that generates a false consciousness of one’s actions and leads to the grounding of the individual in an order, where there is no primordial signifier to relieve the individual from the binds of language. In the poem instead, there is an attempt to decipher the place from which language originates. The fact that ‘I’ has been folded into itself and that the action of the ‘we’ comes to be ironically undermined by the very fact that it is overstated, shows the poem’s undesirability of assuming the “false being” of a subject who corresponds to the external reality by believing itself to be the sole generator of ideas. What the poet tries to demonstrate in the poem is not so much how the individual should act upon the world, but stress upon the manner in which the individual is related to the world.

The function of language in the poem can itself be taken to be an allegory of the end that the poem seeks to achieve. The poem facilitates the process through which the individual comes to assume its position in language, by refraining from according substantiality to the subject signifiers and by depicting that the subject is in itself a set of relation between terms, between the ‘I’ and ‘we’, between the ‘he’ and ‘they’, that is, between the numbers. The poem does not fall under the trap of complicity as it questions the axiomatic of the very structure that harbours it. The sentences that break off in aposiopesis, the words, although retaining a logical sequentiality from one sentence to another, perambulate the entire process of meaning production, serve as a linguistic paradigm for the social reality that it projects. Social reality is fissured, is laid bare amidst the discursive processes. It is because of this reason that, although we are ‘surrounded’ and ‘unhopeful’, we must still “wish for them: / elect the principal.” The disruptive composition of the poem, the interstices generated between the generation and reception of meaning is synchronous with the workings of a society, where reality is never complete in itself and meaning comes to be generated in the liminal spaces. The structure of the poem thus serves the purpose of cultural critique.

Throughout the poem there is a degeneration of the signifiers for the self. The subject comes to be positioned through the actions that she/he is forced to partake in, actions that through their repetitiveness have lost their meaning, for example, “elect the principal”, and thus end up leaving us with a feeling of being “too surrounded, unhopeful.” The materiality of being is thus reduced to certain repetitive actions that bind the individual to the state. However, we find that the phrase, “We are alive” puts a particular emphasis upon the sense of being in itself (emphasis on the italicised ‘are’). Throughout the poem there is an emphasis upon the materiality of the individual, by referring to the skin and the ‘white charge in the bones’. The instance where the poet presents “The politics…a question of skin” is crucial, as it presents the entire question relating to politics being an abyssal choice that has no basis in the symbolic order. The question of politics, as the poem propounds, is something that comes to resist the symbolic order of language, and becomes instead an instinctual response, a response that is embodied, inherent, with no individual choice. The political decision made by the people has no basis in the cognitive order, and comes to be characterised by another metaphor used in the poem, “walking is…without even a shred of desire/ like maps at our feet.” The bones and the skin in the poem, thus, become the points which consign as well as prevaricate the functioning of power.

The poem ends with an attempt to overcome the dehiscence that comes to be instituted between the self and the external world through the functioning of language. The poem attempts to uncover the elemental thing, the other thing that exists before the “terminal systems”, the thing that floats “in the air.” The significance of this line is in the fact that it leads to the forging of the poem’s bond with organicist trends. The poem hints at trans-historical truths although at the same time retaining an indefatigable association with the particulars of person and circumstance (as elicited by its stress upon figures like William Smith[8], silver mining etc). The penultimate indented line, “One is each: and in/ succession” hints at the fact that the self, so long struggling between the markers of ‘I’ and ‘we’ can now come to find solace in the comfort of the singular, the ‘One.’ However, even then, we are not sure whether the poem is appeased by this sublimation of garrulous multiplicity; whether it signifies that the reinstitution of the ‘One’ can never be an exodus into the primordial self, away from the signifying structures of language, but is instead a poor sacrifice required by the tenets of modern, social existence.

In the lines:

These are the ligatures to

revise governance,

of the local disposing, the

quality as firstly position.

here is the elect, the

folds of our intimate surface (Prynne 12)

Prynne is concerned with the limits of the type of place, stressing on the ‘unconcealment’ of procedures which shifts the notion of power in an economy contained within the immutability of stone (in primitive societies) to an abstraction of power residing in the very act of shifting the value from one object to another. The very ontologically consecrated notion of place in Prynne is thus questioned as he studies place in terms of fluctuating economic signifiers:

According to Prynne’s model, the transition to a system of property not only couples substance with death but also “produces the idea of place as the chief local fact” (127). Place offers a mediation between an abstract economic function (mining or agriculture, for example) and the materials which guarantee a money economy. (Blanton 132)

Prynne’s writing harbours a predisposition to view the nation-state in terms of the apposite binary of substance and quality. The “difficult matter” referred to in “The Numbers” could be referring to this problematic. The 1967 prose text A Note on Metal [as discussed earlier, first appeared in Aristeas (1968), essentially differentiated from the three poems contained in the volume and was included in the collection The White Stones (1969) again appearing in the 1982 collection] Prynne speculates how a change in the notion of substance is instrumental in effecting changes in the notion of economy, exchange value and as a consequence the manner in which the individuals connect with the surroundings around him.

Reeve and Kerridge in their book Nearly Too Much Prynne emphasizes that the problem of excess during the period of high modernism had made the theoretical apprehension of the idea of the whole impossible to attain. In Prynne however, this excess is not treated as disadvantageous to the aesthetic space of the poem. Instead it allows the freedom to exculpate a wide range of possible attitudes that placed within the ‘freedom’ of consumer culture allows for the construction of an identity that is dependent upon multiple factors: the intractable materiality of economic spaces, the elusive propounding of theological vantages. It then helps structure a language which cohorts with the affective in nature.

The ever-evolving nature of economic capital and the ways in which it infiltrates into the lives of individuals, creating a vortex of competing human possibilities is present as a direct concern in most of Prynne’s poems from the first two poetry collections. The poem “Die a Millionaire” begins with the lines:

The first essential is to take knowledge

back to the springs […] (Prynne 13)

In Prynne’s characteristic way, the lines wilfully enact a semantic knot that brings together the spiritual and the economic. Springs are traditionally seen as spiritually charged places within Old Testament Narratives (Moses striking his ground with his staff and water gushing out is an effective example). It also connects with the idea of Jesus being the “water of life.” This semantic dimension of springs therefore brings about a theological imbuing of meaning to land which is constituted in our symbolic space as a resource, the division of which comes to constitute the state. ‘Springs’ also refer to the technological control systems that puncture the landscape and generate products (in this case bottled water) that cater to need that has also been instated by the processes of cultural mediation in English society:

The fact is that right

from the springs this water is no longer fit

for the stones it washes: the water of life

is all in bottles & ready for invoice […] (Prynne 15)

In Springs and Bottled Waters of the World: Ancient History, Source and Occurrence, La Moreaux and Tanner chart the ways in which the soil of Britain is characterized by migratory springs. They mark the way in which in the later-half of the twentieth century there has beena rise in the production of bottled water.

In recent years, there has been a dramatic growth in the bottled water industry in the United Kingdom, all the more marked, perhaps, because usage of bottled water seems to have lagged behind that of continental Europe. Perhaps, the British, in their dogged insularity, put a greater faith in the purity and quality of their public water supplies than their continental counterparts, but whatever the reason, nowadays the supermarket shelves all carry a good selection of “still” and “carbonated” “natural mineral water.” (Moreaux and Tanner 143)

For Prynne, the space of the nation is problematized by the ever proliferating means of economic expansion. What becomes a marker of the national identity is the water which can be marketed and sold. It is the “mass conversion of want (sectional) into/ need (social & then total)” (Prynne 15), that comes to define one’s presence in the community. The anagogic means of seeing the land as a spiritual construct where meaning is present within the soil is placed under duress in the late capitalist state. It has commoditised the land’s resources to such an extent that it corrodes all other ways in which the individual can connect to the land. In another place he writes, “what starts as irrigation ends up/ selling the megawattage across the grid.” (Prynne 14). As in the previous poem where state was seen as differed subjectivity, in this poem Prynne studies the economic processes that underlie the function of a democracy, where though “we all share the same head, our shoulders/ are denied by the nuptial joys of television” and where our ontology of being is ultimately a perverse form of our purchases (“what I am is a special case of/what we want [...]”).

By acknowledging the prevalence of these varied discourses, Prynne’s poetry consciously acknowledges the necessary changes that society underwent in the period of late capitalism.[9] Due to the changes that have been called into effect through the changes in the features of capitalism, there are definite instances in Prynne’s writing acknowledging the ways in which the sense of the world’s perception has also evolved. On the one hand we find in Prynne a reluctance to specify the particularity of the place that he belongs to and this can be paradigmatically connected to the fact that the monopoly stage of capitalism has now distended itself and extends beyond the confines of any national border. The most telling factor of this development is, as Lefebvre states, the material connection built between social space (spatial and signifying social practices) and actual physical space. He declares,

Space thus rejoins material production: the production of goods, things, objects of exchange—clothing, furnishings, houses or homes—a production which is dictated by necessity. (Lefebvre 137)

Prynne’s lines in “Die a Millionaire”, documents the way in which this mass drive of necessity is characterized:

but the waste produced by

mass-conversion of want (sectional) into

need (social & then total). All this by

purchase on the twist-point, the system gone

social to disguise (Prynne 15)

The production of the nation-space is therefore dictated by the principles of necessity as rightly rejoined by Lefebvre. In Prynne also there is a proclivity to study the relation of the land to the individual in terms of the need predated upon by the development of the forces of capitalism:

so that what I am is a special case of

what we want, the twist-point missed exactly

at the nation’s scrawny neck. (Prynne 16)

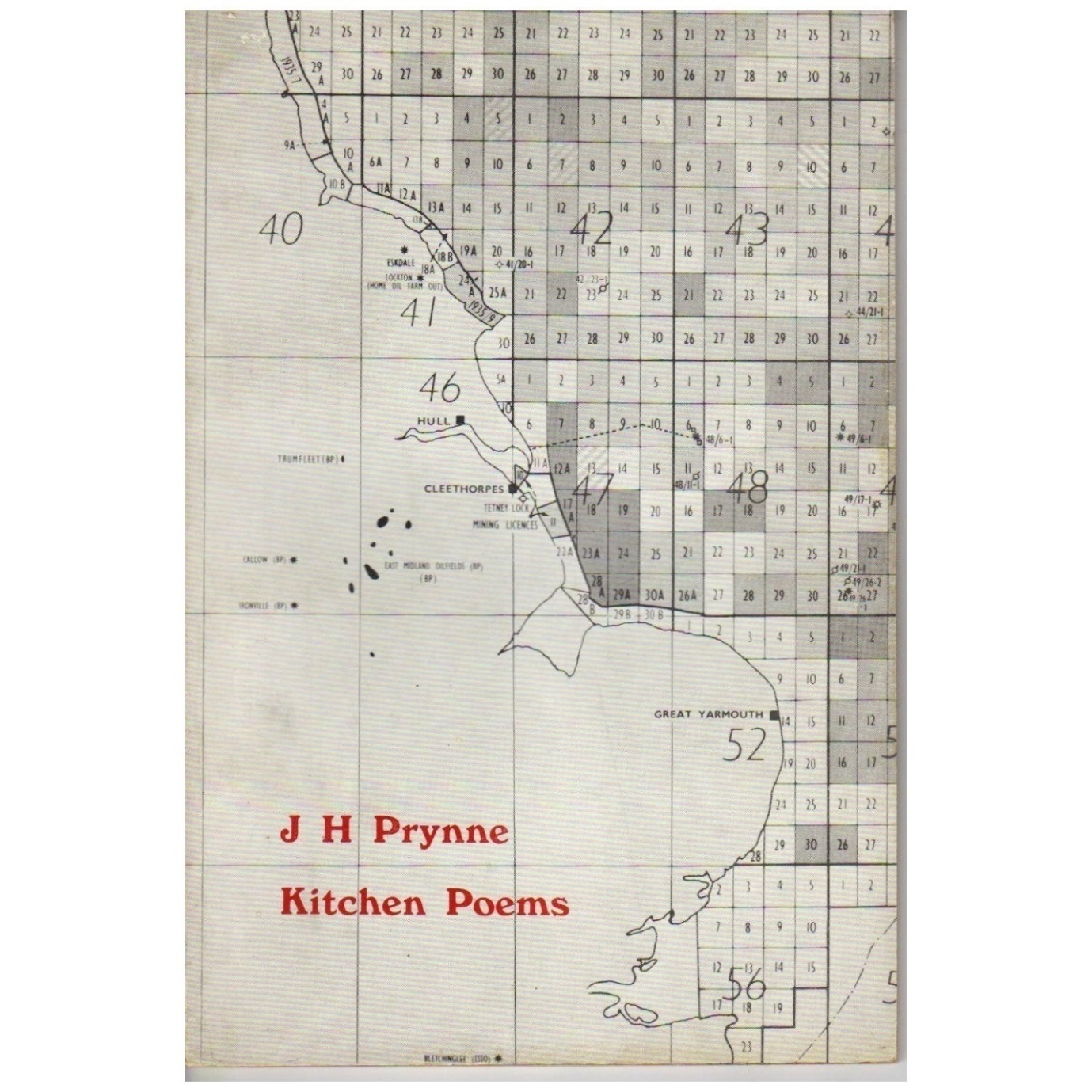

The individual’s position very clearly comes to be determined here through his/ her relation to the nation as a whole. To prefigure subjectivity as a special case of “what we want” makes post-imperial subjectivity as completely incumbent upon the decisions taken by the multinational companies that quite literally may be said to be moulding the future of the country. Again, the term “twist-point” is very important in Prynne especially with regard to the conceptualization of the poetic collection itself. The cover of the Kitchen Poems cartographically depicts a line map of the north-east of England and the North Sea presenting a detailed representation of the location of oil fields and refineries. The cover’s objective, empirical, commercial representation of British geography conveys to the reader in the briefest synaptic transmission, an understanding of the landscape as irrevocably conciliated by commercial interests and industrial processes. Not only do the poems in the collection contravene the meaning generated by the oil map representation of Britain, but at the same time redefines the ways in which the needs of the land can be made commensurate with the needs of the individual. The use of the term “twist-point” melds together in an aleatory act of the imagination— the breaking point in economy, to the twist-point of the oil wells. Twist-point ideally refers to a breaking point, whether it is in economy, or in physics, where the grip breaks and engenders a new form of functioning. The Oxford English Dictionary also documents the ways in which the term is used with respect to engineering and reports that in 1962, travel controls consist of a twist-grip where “the amount of twist govern[s] the speed of travel” (OED 1033). Twist in a very significant way also connects to the bilaterality of the body. Kant in his short essay entitled “Concerning the ultimate ground of the differentiation of directions in space” (1768) talks of the way in which the twist in the body’s bilaterality makes it possible to differentiate the right from the left. In other words, “the directedness of places and regions—of the things situated in them—stems ultimately from the symmetrical bilaterality of the very body that is responsible for their orientedness” (Casey 209). The word “Twist” therefore allows for a semantic conjunction between the breaking-point of the economy and the orientation of the body.

The “purchase on the twist-point” correlates Prynne’s concern about the economy, his post-imperial concern for British identity, his approbation of ‘quality’ that cannot be devolved into that of the ‘substance.’ In his essay, A Note on Metal, Prynne equates the debasement of metal through alloying as effectively looking forward to the weakening of bonds between money and commodity. Adrian Price, a psychoanalyst who wrote a review of J.H. Prynne’s Poems says in his article:

[…] the weakening of the bonds between money and the vestigial money commodity that we meet in the twentieth century economics, a weakening that has advanced to the extent that now one speaks only of the possibility of a viable numeraire, in place of the abandoned gold standard. (Price 3)

The twist point refers to the point in history when America under the rule of John F. Kennedy instigated a series of changes in the economy that put an end to America’s disastrous outflow of gold to Europe resulting in America’s ensuing recession period. Operation Twist however prompted a change in the economy that attenuated the value of the European gold standard and brought back an economic boom in America thereby further excoriating England’s post-imperialist woes.[10]The task of locating a concrete sense of the late capitalist, post-imperial British identity; an identity that can no longer derive its sense of quality from the indubitable prestige of the gold standard falls upon a new form of representation.

Again in “Die a Millionaire”, the ‘grid’ of knowledge is interpreted as cartographic charting of the resources of the land, excavated for the “intangible” consumer:

The grid is another sign, is knowledge

in appliqué-work actually strangled and latticed

across the land; like the intangible consumer

networks, as the market defines wants from

single reckoning into a social need, […] (Prynne 14)

The maps that harangue the representational consciousness of Prynne do not merely that catalogue the expanse of physical space— they are grids that map the power resources of the land (hydraulic energy, coal), electricity. It is however important for us to note that the objective representation of the land does not show a disregard for the significant confluence of the historical and mythical. Instead, it should be perceived as a response towards late capitalist obsession with surfaces. Prynne’s poetry attempt at making the land ‘imageable’, visually articulate, where land as an immanent entity and land as resource become commensurate, enabling the individual to better understand his function as a citizen of a nation whose ontological basis of identity is constantly changing. His language as has been argued can be seen as best negotiating with the syncretisms of the media, the developments constituting an economical self while at the same time communicating a sense of the communal self, located within the master signifier of the nation-state. As argued earlier, Prynne’s poetry effectively goes forth to ascertain the ‘situating’ of the nation-state across the symbolic identifications that individuals share with the ‘other’ in a democracy and the identifications that are emplaced at the macro-level with the body of the nation through various commercial and representational practices. The nation that emerges through Prynne’s poems no longer remains an empty signifier but appears as a process of integration, where the past, present and the future converge in the veritable ‘now’ of language’s present.