Heidegger Contra Lacan: The Cut and the Development of Two Theories of Subjectivity

Eric VanLieshout

Foundations: On a Tradition and Its Discontents

Neuroscience, Psychology, Biology, Computer Science, artificial intelligence, and post-modern philosophies are all converging at a single node: trying to understand consciousness and the self. With these researches the understanding of consciousness is becoming more complex and the conceptual hegemony of the unified, individual Self or the Knowing Self is becoming increasingly precarious. Since the question “what is consciousness?” is concomitant with “what is conscious?”, the question of the subject and subjectivity is being broached with a new urgency. Traditionally, Western philosophy (generally complicit with Western science and medicine even today) has conceived of a subject of knowledge, and assumed a subject that could come to fully know itself, its reality, its mechanisms, its why and how. As this formulation becomes increasingly difficult to maintain against the revelations of various scientific, psychological, and philosophical researches, there is a call for renewed efforts in thinking or modeling the traditional subject of knowledge that has been posited by Western metaphysics and science. By examining two radically divergent theories of the subject, this paper will explore one method for re-modelling or re-forming the idea of the subject and subjectivity: the integration of internal divisions, splittings, or cuts.

The knowing subject, this traditional philosophical subject, has undergone a number of developments and delimitations throughout the history of philosophy and science (knowledge), from the Greeks through to Descartes and German Idealism and into the contemporary era in analytic philosophy and scientific discourses. Nonetheless, for all the delimitations and circumscriptions that have reduced or restricted it, there remains posited the guarantee of completeness and unity; that given sufficient information and reason, this subject can be known fully, and moreover can know itself fully. This situation has been complicated by gaps in knowledge, by the apparent irrationality of certain matters, and by contradictory phenomenon both internal and external to the subject. Hysteria, with the beginnings of neuroscience and medical treatment of mental illness, is perhaps the major turning point where for the first time the idea was taken seriously, scientifically, that the subject could split itself in twain and that this splitting (Spaltung) could be something structural. The general idea of the splitting of the mind lies at the heart of Freud’s formulation of psychoanalysis, becoming a primary structure (associated as it is with repression, the unconscious, the ego/id, etc., to say nothing yet of the place of the cut in Lacan’s thinking). Interestingly, philosophy seems to have lagged behind the medical community, and – as this paper will demonstrate – Heidegger is the first to locate a structure of splitting or a gap in the very constitution of his (quasi-) subject, Dasein. Nonetheless, Freud and Heidegger each posited fundamentally new formulations of the subject.

It is Lacan, however, who more fully developed Freud’s structures of splitting into the complex and multiple subjectivities available to the speaking, human being in Lacanian psychoanalysis. Following some introductory comments on conventional Western subjectivity this article will focus on specific ways Heidegger and Lacan develop theories of subjectivity in their foundational works in order to demonstrate how these theories constitute exceptions to the traditional theories of the knowing subject. For Heidegger, this means looking closely at the development of Dasein in Being and Time with a particular focus on the instances of cutting or splitting that distinguish Dasein as a radical break with the traditional subject of philosophy. In so doing, Derrida’s recently published 1964 lectures, Heidegger: The Question of Being & History (2016), will offer some key insights into Heidegger’s text. Next, it will be shown how Lacan, closely examining Freud’s theory of the Oedipus complex and psychic development, develops an even more complex and dynamic notion of subjectivity in his recently translated (2017) fifth seminar, Formations of the Unconscious (1957-1958). This discussion will, as with Dasein, focus on the role of splitting or the cut in psychic development, further developing Freud’s already radical work on the splitting of the mind that yields a subjectivity fundamentally different from Western philosophy’s traditional subject.

Both Heidegger’s Dasein and Lacan’s thinking of subjectivity diverge from the traditional philosophical subject on the basis of their different relation to the cut or splitting that bars them from any objective self-knowledge. Through this general idea of cutting or internal division, Dasein and Lacan’s subject come to differ from the traditional subject on two main bases: they have radically different relations to history and language than the traditional subject. Moreover, tracing out how these subjects are conceived in relation to processes of cutting or splitting brings about a new manner of understanding and approaching subjective positions vis-à-vis knowledge, the development of self-consciousness, and – through the role of language – community. In the end, the developments from the philosophical subject to Dasein and Lacan’s subject will indicate how increasingly verisimilar human subject theories can be developed on the basis of increasingly complex relations and integrations of structural splitting.

The philosophical subject will be taken here as a background, the third term against which Dasein and Lacan’s subject stand out. It is only as a background that it has any interest here, and so, a long tradition will be abridged accordingly. It is thus only necessary to provide a brief overview of the traditional subject in order to show how Dasein and $ deviate from this tradition (through the integration of the function of the cut). Only with this elucidation in place can the comparison between Dasein and Lacan’s subject take place and demonstrate the full potential of rethinking models of the subject, based on the function of the cut.

The history of philosophy shows a great variety and complexity in the ways the philosophical subject is thought, and yet the philosophical subject is roughly speaking taken as a given and a whole. While this may seem reductionist, this delimitation is in fact less reductionist than it is an orientation or a re-orientation in the conception of this subject: it is a matter of thinking the philosophical subject strictly apropos the cut. The philosophical subject, as Lacan summarizes in Formations of the Unconscious, is a soi-même, a “self” (Lacan uses the English word specifically) (451); this self is taken as given, and to this self befalls the burden of understanding its place within the world. Despite the numerous cuttings, splittings, divisions, etc., that run through philosophy, from Plato’s idealism and Descartes’ cogito and its mind/body problem, through to Kant’s Reason and its a prioris and Hegel’s Spirit, there is always somewhere cached a solid, whole, unified thinking self against which knowledge can buttress itself. For Descartes, for example, in his Meditations on First Philosophy, illusion must be understood and reasoned out to gain true self knowledge, and an understanding of oneself, its ontology, epistemology, ethics, cosmology, and so on. Reaching an apotheosis in Hegel, the self can always come to know itself by attaining Absolute Knowledge.

This ideal of knowledge goes through modifications but nonetheless there remains an unquestionable self to which all knowledge and reason refer. Hegel’s absolute knowledge and spirit reframe the splitting of the self into an infinite dialectic at the end of which Spirit knows itself in itself and for itself (an und für sich). The philosophical subject, however complexly conceived, retains the position of ultimate observer, the ideal that from some vantage or another some entity could know absolutely itself and its existence and world. Sometimes this vantage is only virtual, sometimes literal, but it always forms the basis upon which the philosophical subject thinks itself. As demonstrated by Derrida’s early deconstructive efforts in Of Grammatology (1967) and Writing and Difference (1967) (written essentially contemporaneously with Heidegger: The Question of Being and Philosophy (1964)), the philosophical subject is part of the metaphysics of presence, and thus lurking somewhere behind all the different formulations of philosophical subjectivity is a consciousness fully present to itself, capable of being fully self-possessed, fully and certainly knowing and thinking itself.

Carving Out a New (Quasi-)Subject: Heidegger’s Dasein

Still ostensibly within the more traditional domain of philosophical research, Phenomenology, as inaugurated by Husserl, leads Heidegger to radically reformulate and relativize the basis of subjectivity through the analytic of Dasein, a phenomenological subject radically different from the philosophical subject. From one standpoint, Dasein is prior to the philosophical subject which as per Derrida is part of the metaphysics of presence and of what Heidegger calls secondary history. But while this distinction “pre-” is important, it is not the whole story. In essence, Heidegger’s major achievement is the formulation of a subject (so to speak), Dasein, that appears to itself as it is cut out of its surroundings and out of its own being (cut out from its own past and future). Dasein realizes itself not as some given entity ‘over there’ but the as the reference against which any sense of a ‘here’ or ‘there’ is experienced. Dasein experiences itself as cleaved off from a ‘there’ as a ‘not-there’: it is thrown out and back onto its ‘here,’ and this referential ‘here’ becomes a de-facto self. Thus, Dasein is through constant reference to what it is not: it is not there, it is not others, it is not ready-to-hand, it is not the world, it is not its future, etc. The existentials and existentiells of Dasein are always referential, and thus at the most basic root-level Dasein is relativistically. At this point an objection might be raised, since the traditional philosophical subject has been at times situated similarly in a negative way, as what it is not; the difference is that with Dasein, since its own being is an issue for it, there is no core of certainty or teleology that ensures its emergence on the other side of a dialectic or analytic. Dasein is thus radically relativized. This uncertain non-teleological dependence on its surroundings leads logically to the fact that Dasein must be historically. Historicity is part of Dasein’s mode of being, as the being for whom (its) being is an issue, precisely because Dasein builds itself, in its being, and yet is never certain of its completion or incompletion. Dasein only ever is to the extent that it has been disclosed to itself – “Dasein is its Disclosedness” (2010 129/133).

Heidegger’s Dasein is the first properly historical subject, in contrast to the markedly ahistorical philosophical subject. This is what Derrida, in his lectures on Being and Time entitled Heidegger: The Question of Being & History, means in explaining that the philosophical subject (the Hegelian-Husserlian subject) is a substance onto which history is graphed, and Dasein in contrast is not a substance prior to history that serves as a medium or avenue for any of various histories but rather is itself a being who is historically. As Derrida explains:

The Da-sein that is designated by the name subject does not become historical by getting entangled in sequences of givens, in “circumstances” (Umstände), that would come to surround it, press in around the subject who would on this view be the present, the upright presence, the status and subject of history. On the contrary … is it not because, in a sense to be elucidated, Dasein is already historical in its very being that circumstances, Umstände, givens, a destiny can … concern it? …

… the dimension of subjectivity supervenes on a historicity of ek-sistence, of Dasein. The historicity of Dasein is originary but it is not originarily determined as subjectivity. Which means that it does not originarily appear to itself as subjectivity and that it is not originarily subjectivity. Dasein (ek-sistence) is originarily history, and it happens in the course of its history that it constitutes itself and appears to itself as subjectivity, for essential and necessary reasons….

Once again, in spite of appearances, we are not here speaking a Hegelian language. The point is not to say that substance becomes subject, that there

is a becoming-subject of a substance that for Hegel is absolute substance….

The fact remains that for Heidegger subjectivity does not supervene upon a non-historical absolute that awakens to it (Substance, Present). It supervenes upon an experience or an ek-sistence that is already historical….

(171-175)

In other words, Dasein relies on a temporalizing-historizing to situate itself. The advent of Dasein is an accumulation and agglutination of existentials, of cuts and cleavages and deseverences per Heidegger’s analytic. This accumulation can be laid out in an analytic but for Dasein it is always “experienced” as already having happened, an inaccessible pre-history. As such – and Derrida reiterates this point many times – Dasein is the first conception of a “subject” that is not an a-historical substance present to itself and metaphysics, and that accordingly breaks with the traditional transcendental unity or (self-) presence upon which the philosophical subject relies.

Concomitant with the intrinsic historically-determined quasi-subjectivity of Dasein, Heidegger also places a newfound emphasis on language. If Dasein is through constant, historizing referencing (its disclosedness), then its being, or the issue of its being, is communicated to it discursively.

In Being and Time, Heidegger discusses language in the fifth section of the first division of part one, “Being-in as such.” The previous four sections, as Heidegger explains in the first subsection (paragraph 28), were oriented outward, carving out from a world, the place and self of Dasein, but ends with a particular problem that has haunted all philosophers:

Authentic being a self is not based on an exceptional state of the subject, detached from the they but is an existentiell modification of the they as an essential existential… But, then, the sameness of the authentically existing self is separated ontologically by a gap from the identity of the I maintaining itself in the multiplicity of its experiences. (2010 126/130)

The analysis of Being-in doesn’t, as might be expected, close this gap. Rather, Being-in, which is also a being-there and thus entails the ontology of this “there,” proceeds to make this authentic being-one’s-self (i.e. the being disclosed to itself) the outcome of fundamental existentials, such as meaning and understanding, which Dasein manages through discourse, and so through language. As Heidegger writes,

Intelligibility is … always already articulated before its appropriative interpretation. Discourse is the articulation of intelligibility.… If discourse, the articulation of the intelligibility of the there, is the primordial existential of disclosedness, and if disclosedness is primarily constituted by being-in-the-world, discourse must also essentially have a specifically worldly mode of being. The attuned intelligibility of being-in-the-world expresses itself as discourse….

The way in which discourse gets expressed is language. This totality of words in which discourse has its own “worldly” being [Sein] can thus be found as an innerworldly being [Seiendes] like something at hand. Language can be broken up into world-things objectively present. Discourse is existential language because the beings whose disclosedness it significantly articulates have the kind of being of being-in-theworld which is thrown and reliant upon the “world.”

As the existential constitution of the disclosedness of Dasein, discourse is constitutive for the existence of Dasein.

(2010 155-6/ 161)

It is clear, thus, that the gap within Dasein’s being mentioned at the end of the fourth section is not closed but relocated within discourse and, with it, language. Indeed, “[D]iscoursing is the ‘significant’ structuring [Gliedern] of the intelligibility of being-in-the-world, to which being-with belongs, and which maintains itself in a particular way of heedful being-with-oneanother” (2010 156/161). The older MacQuarrie and Robinson translation is worth quoting, too, for comparison: “Discoursing or talking is the way in which we articulate ‘significantly’ the intelligibility of Being-in-the-world. Being-with belongs to Being-in-the-world, which in every case maintains itself in some definite way of concernful Being-with-one-another” (1962 204/161). The gap separating an I and its manifold of being-with (the self) is bridged by a discursive position, and the gap reappears within the articulation of Dasein’s being-with (and being-with is the ground for self). Following from this, Heidegger explains Being-in-the-world as discursive Being-in: “Since discourse is constitutive for the being of the there … and since Dasein means being-in-theworld, Dasein as discoursing being-in has already expressed itself” (2010 159/165). For Heidegger, this means “Dasein has language” (ibid.).

So, Dasein is discursively, that is, Dasein is through language. The temporal analytic, for example, bears this out in its reliance upon linguistically based concepts of then and now, beforehand, earlier and later. These words, taken together signal in essence a discursive temporality of relativities. And these significations, linguistic and temporal, must accrue and come to constitute a whole – this is why Dasein is always already a historical being; per Derrida’s terminology, Dasein is a historizied (quasi-)subjectivity. And it is in this way that Heidegger manages to make Dasein into a whole, by shifting the gaps that separate Dasein from itself, from its relational modalities of being, onto language. Explicitly, “this phenomenon [language] has its roots in the existential constitution of the disclosedness of Dasein. The existential-ontological foundation of language [Sprache] is discourse [Rede]” (2010 155/160, Heidegger’s emphasis). The foundation of language for Dasein is the bridging of a gap through the intelligibility of discourse. Again, “discourse is constitutive for Dasein,” language becomes internalized and with it Dasein finds the means to bridge gaps that otherwise separate it from itself. Its self-knowledge, its subjectivity, is not transcendent or self-evident, but fundamentally discursive and linguistic.

The Subject developed in Lacan’s Formations of the Unconscious (1957-1958)

Although Dasein breaks with the philosophical subject, thus, Heidegger and Dasein still remain engaged with traditional philosophical research and philosophical questions. Psychoanalysis, however, is not a traditional philosophy and its researches are organized differently. Instead, psychoanalysis “is governed by a particular aim, which is historically defined by the elaboration of the notion of the subject”; moreover, psychoanalysis “poses this notion in a new way, by leading the subject back to his signifying dependence” (Lacan The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, 77). There is only the subject first and foremost and the rest of the world follows only as necessity, whereas even with Heidegger Dasein is but a privileged point of access through which to investigate the (always subjective) world and reality.

Lacan, widely read himself in Western philosophy, spends a great deal of time throughout his career explaining how his conceptions of the subject and subjectivity differ from the philosophical subject – Descartes and his cogito, in particular, are a major point of reference and distinction for Lacan. The stable core of the philosophical subject best appears in the philosophical developments of self and consciousness (and thinking, reason, etc.), and it is against these developments and shifts that Lacan often tries to explain the uniqueness of his conceptions of subjectivity. The shift from Plato to Descartes, for example, is a shift from the pursuit of an idealized knowledge of self to a more nuanced self-knowledge, cognizant of a split between the rational and irrational. Prima facie, this split Descartes finds, appears to mimic the basic Freudian Spaltung, but there is a crucial distinction. Dany Nobus and Malcolm Quinn succinctly summarize how Lacan conceives the relation between the Cartesian cogito, the subject of the unconscious, and the cut in their book Knowing Nothing, Staying Stupid (2005):

Lacan forged a link between the Freudian split (Spaltung) and the Cartesian cogito. Descartes’ courageous distinction between the commonality of thought processes and the ‘accidental’ character of the individual mind, which enabled him to define his own intellectual limitations with clarity and certainty, also cleared the way for the concept of the unconscious. Descartes took the first step towards conceiving of thought as divided into the occasional and fleeting nature of conscious apprehension, and a structured set of relations, a constant and uninterrupted movement of thought that is both impersonal and common to us all. Lacan argued, however, that Descartes was unable fully to approach the unconscious because of his insistence on retaining the existential “I.” Indeed, Cartesian skepticism initiates a rift between knowledge and truth, but this rift is bridged by the existential “I.” (107-108)

Thus, as Lacan observes, despite Descartes’ cleaving in twain of a prior philosophical self, he nonetheless retains a complete self, imperfect but whole, supported by a transcendental reference in effect reminiscent of Platonism. As such, Lacan can only say that Descartes opened a space within the psyche for something like an unconscious while still retaining the traditional philosophical subject, reason, and knowledge.

For Lacan, building on Freud, the subject here is cut off from itself, from its self – it is subject to the unconscious – and this basis develops into the manifold and dynamic subjectivities in Lacanian psychoanalysis. Again, this basic formulation appears prima facie commensurate with the Cartesian cogito and the problem of truth-versus-illusion and the rational-versus-the irrational. But Descartes’ cogito, and the philosophical subject broadly speaking, are not profoundly (internally) divided by Lacan’s triumvirate of unconscious, desire, and signifier. This triumvirate institutes a rift in the subject that cannot be spanned by any transcendental “I” or (self-) knowledge. Self-observation, self-reflection, and reason – the mainstays of philosophical research – are stymied by a cut, a Spaltung, and they become inadequate.

This rift traces back directly to Freud’s conceptions of splitting and ego-splitting, Spaltung and Ichspaltung. Formations of the Unconscious carefully traces out the genesis of this splitting (picking up where Freud literally left off with his uncompleted 1938 article “The Splitting of the Ego in the Process of Defense”) and the pivotal place this splitting occupies in the development of the human being as a subject, that is, as a subject of desire. As he explains in Formations of the Unconscious:

$ is the subject as such, a less complete, barred subject. That means that a complete human subject is never a pure and simple subject of knowledge, as all of philosophy constructs it, well and truly corresponding to the percipiens of this perceptum that is the world. We know that there is no human subject who is a pure subject of knowledge, save reducing him to … what in philosophy is called a consciousness. But as we are analysts, we know there is always a Spaltung, that is, there are always two lines along which he [the subject] is constituted. This, moreover, is where all our problems of structure originate.

(373)

Moreover, again, these two lines over which the human being is constituted are not simple but manifold.

Lacan’s fifth seminar traces step by step the development (i.e. historicizing) of the infant into a subject and leads directly to this formulation of these two lines and their Spaltung. It is worth reviewing briefly some of the key aspects and splits entailed by the barred subject. To begin with is the well-known conscious-unconscious divide, and splitting the subject’s knowledge such that some of it remains inaccessible to the subject and consciousness. This unconscious knowledge bears directly on desire, the subject’s desire, which is always – from the Oedipus complex – the (m)other’s desire. Freud observes, and Lacan develops in this seminar, the postulate that the Oedipus complex begins with the child’s demand to be loved (and as this demand comes to be expressed in language, the gulf opens up between demand and desire). The infant wants, or needs, to be wanted, and it comes to want to be what the mother wants; classically, the mother wants the father, and something the father has.

The other’s desire is, by the infant, posited in the other’s other, and so the infant begins to posit something that satisfies the other’s desire, and then the infant’s desire in turn. This way the human passes into and through the “defiles of the signifier” (per Lacan’s oft-repeated phrase) and becomes a speaking being. The signifier allows the subject to become a speaking being, enter into the dialectics of desire, and become a complete human being – it is worth noting Lacan’s repeated use of the term human being in Formations of the Unconscious, reiterating that psychoanalysis is first and foremost concerned with the clinic and lived reality, instead of idealizations and rational models. But while the signifier implies a signified, an implication born out with the appearance of the phallus, this signified remains only implied, meaning there is only ever a signifier for the signified, or desire – namely, the phallus. Thus, desire bifurcates into two parallel tracks which produce only the illusion of reconciling at an infinite horizon; this horizon is precisely the object of desire:

What we are here calling the mother’s desire is a symbolic label or designation of what we observe in the facts, namely, the correlative and fractured promotion of the object of desire into two irreconcilable halves. On the one hand, what on our own interpretation can be put forward as being the substitute object…. On the other hand, this element of desire itself, which is tied to something extraordinarily problematic and, also, presents itself … with the characteristic, let’s use the word, of a signifier. Everything happens as if, as soon as it’s a question of an unconscious desire, we find ourselves in the presence of a mechanism, a necessary Spaltung which makes desire … appear here as marked, not only by the need for an intermediary in the other as such, but also by the mark of a special signifier, a chosen signifier, which here happens to be the obligatory path which, as it were, the course of the vital force, desire in this case, must follow.

The problematic feature of this particular signifier, the phallus, is the question.…

… We thus always misrecognize, to some extent, the desire that wants to be recognized, inasmuch as we assign an object to it, whereas it’s not about an object – desire is desire for this lack which, in the Other, designates another desire.

(309)

Returning to the difference between Lacan’s subject, $, and the philosophical subject, it is clear that Lacan’s is fundamentally subject to an unknown and foreign desire that cleaves it from itself and that forces it into an existence as a less complete subject of knowledge, operating in ignorance of what is nonetheless impelling it forward. And this, too, is a key point: Lacan’s subject is impelled, driven through signifiers along an opaque and anfractuous path of desire. This is in stark contrast to the disinterested, objective, strictly rational philosophical subject. Later, in The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis (1964-1965), Lacan places his exploration of the subject in a sustained dialogue with Descartes that entails the dictum “Desidero is the Freudian cogito” (154).

With this it should be clear that, like Dasein, $ is both intrinsically historical via the Oedipal process and articulated via discourse and language; these two axes are constitutive of desire, which develops with an unconscious, unknowable, or a priori historicality via discursively organized signifiers.

Unlike Dasein, however, the barred subject has a much more complicated relation with language. For Dasein, language and discourse are solutions, in a manner of speaking. Dasein, in its mode of being, “has language,” Heidegger writes (2010 159/165), and while Heidegger, in Being and Time, does define language, and by extension discourse, more complexly than many other philosophers and linguists, he does not divide language internally – he does not make language itself a problem for Dasein. Lacan does make language a problem for $, splitting it from itself through his insistence on the structural necessity of metaphor. This internal splitting of language, moreover, is bound up for Lacan directly with the fact that language is co-extensive with humans and, too, Lacan’s subject. Looking at Pavlovian conditioning in animals, Lacan clarifies the matter thus:

One might wonder why, at the end of the day, when these [Pavlov’s] animals are so well trained, they don’t end up having acquired some kind of language. Now, precisely, this leap isn’t made. When the Pavlovian theory became interested in what happens in man with respect to language, Pavlov took the very correct position, where [human] language is concerned, of speaking, not of a prolongation of significations as it’s brought into play in conditioned reflexes, but of a second system of significations.…

Ultimately, I would state the simplest formula in this way – no matter how elaborate these experiments, what is not found, and what there is perhaps no question of finding, is the law by which the signifiers involved are organized. This comes down to saying that this is the law by which the animals would be organized. It’s completely clear that there is no trace of reference to any such law.…No kind of law-like extrapolation is visible there, and that’s why one can say that no one has ever managed to establish a law. I repeat, this is still not to say that there is no dimension of the Other with a big ‘O’ for animals, but only that, effectively, nothing like a discourse ever comes of it for them.

(319-320)

It is the law, as the guarantor that the signifiers are organized and thus discourse articulable, that elevates complex signifying systems (Pavlovian, etc.) into discourse. This law is the (function of the) Name-of-the-Father: “in order for the dimension of the Other to be fully able to exercise its function as Other, as the locus of the depot or treasure trove of signifiers . . . it [must] also contain the signifier of the Other as Other. The other also has, beyond itself, this Other capable of giving the law its foundation. This is a dimension which, of course, is also of the order of signifiers, and is embodied in people who underpin this authority” (141).

At this point language has not been split per se. Unlike Heidegger’s account of Dasein’s genesis, where it is cut out of the world fully formed, already possessing and possessed by language (the being of which remains an issue for Heidegger and Derrida), Lacan begins, per Freud, with the underdeveloped infant and traces its coming to language and subjectivity through the Oedipus complex. It is during this process that language becomes divided.

The Name-of-the-Father functions as the mark of law, and “within this function you place significations that may be different according to the case, but which in no case depend on any other necessity that the necessity of the father’s function, to which the Name-of-the-Father corresponds in the signifying chain” (165). The paternal function, guaranteed by the mark of the Name-of-the-Father, is that of metaphor, “a signifier that comes to take the place of another signifier” (158). Explicitly, the father is the first metaphor the child experiences, the beginning of metaphor:

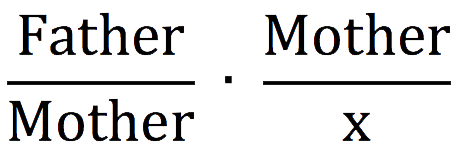

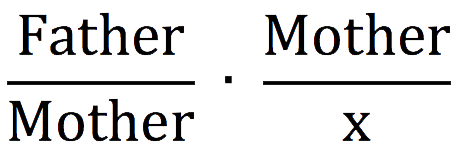

The father’s function in the Oedipus complex is to be a signifier substituted for the first signifier introduced into symbolization, the maternal signifier. According to the formula that, as I once explained to you, was the formula for metaphor, the father comes to the place of the mother, S in place of Sˊ, Sˊ being the mother insofar as she is already linked to something that was x, which is the signified in relationship to the mother.

[…] The question is – what is the signified? What does she want? I [the child, already capable of signification via the mother’s presence and absence] would really like it to be me that she wants, but it’s very clear that it’s not just me that she wants. There are other things at work in her. What is at work in her is the x, the signified. And the signified of the mother’s comings and goings is the phallus.

(159)

With metaphor, the mother falls out of the equation, and the father comes to be the substitute and thus marker of the signified, x. With this we begin to see the second layer of significations, the one Pavlov’s animals lack. With the father comes the promise of a law that imposes an order on the interplay of significations, and orders the child’s access to the signified. Law and order are instantiated with the paternal metaphor:

Effectively, the formula that I have given you of metaphor means nothing but this – that there are two chains, the Ss of the upper level, which are signifiers, while underneath one finds all the wandering signified that are circulating because they are always sliding around. The pinning down I have spoken about, the quilting point, is only a mythical affair, for nobody has ever managed to pin a signification to a signifier. On the other hand, what one can do, is pin one signifier to another signifier and see what happens. In this case, something new is always produced, which is sometimes as unexpected as a chemical reaction – namely, a new signification emerges.

The father is the signifier in the Other that represents the existence of the locus of the signifying chain as law. He places himself, if I may say so, above the signifying chain.

The father is in a metaphorical position inasmuch as, and solely to the extent that, the mother makes him [in the child’s mind] the one who, by his presence, sanctions the existence as such of the locus of the law.

(179-180)

Metaphor divides language from itself within itself, and through the function of the father metaphor is a fundamental and constitutive aspect of the Lacanian subject’s relation with language. This can only be the case if in this relationship the symbolic existence is subject to an order. The law may be unknown, only designated by a name, but here for $ there is a law governing the symbolic; through metaphor (and metonymy) the subject navigates his symbolic existence. This subject, through demand, strives to pin down a signified, to search out the phallus, but due to the paternal metaphor – contemporaneous with the Name-of-the-Father – the subject is banished, cut off from any direct knowledge of that x. This subject cannot give voice to his desire except through metaphors articulated unconsciously –a gap divides demand from desire. The subjectivity Lacan develops here is barred, desiring but unable to signify it, self-ignorant and self-divided precisely because Lacan divides language from itself: the chain of signifiers never ceases and never settles, comes to rest, at any signified.

Obviously, this process, through which the child comes to be the subject of desire, is complex, and a large number of different moments in this genesis have been omitted here. The aim is merely to indicate how for Lacan language comes to be divided from itself even as it is instilled in the very composition of the subject. Furthermore, even with respect to this aim, only the general direction has been indicated here.

To Conclude: Comparisons and Verisimilitude

It should be clear that the splitting of language from itself, along with how this splitting comes to be within the subject, stands as a fundamental difference between the Dasein of Being and Time and the subjectivity, Lacan develops in his fifth seminar that sends each to develop along entirely different paths – and to lead entirely different lives, so to speak. In each case, language becomes internalized and integral to their existence, but Heidegger retains a more structuralist concept of language and discourse. Lacan implements a more complex notion of language. Dasein, although relativized, finds its certainty in discourse, and although discourse is divided between the self and the other Dasein can take discourse and language as secured (there is at least some signifier and signified that are not hopelessly separated). With Lacan, the signifier and signified remain split from each other, and this entails a radical change in the subjectivity of $, compared to either Dasein or the philosophical subject.

Furthermore, both Dasein and Lacan’s subject are historical a priori. The different moments of their genesis must be attained in a certain way such that there is a pre-history of each that leads to an already historical, agglutinated and agglutinative, subjectivity. For Lacan this becomes complicated further by the fact language includes its own history, too – both for the Other and for the Subject, and these histories differ and compete. Through this juncture in language (or the symbolic), history comes to be divided, and there is a splitting within history that redoubles within the subject, the splitting of language. In short, history – as language – is shifted to the interior of the subject for this first time with Dasein and $, but the relation of this history with the cut (whole or split) sends these two subjectivities on entirely different theoretical trajectories.

As a final point of comparison, even the idea of splitting or of the cut is more complicated for Lacan. Heidegger does in fact split all of Dasein’s experiences, including language and discourse, into two aspects: the authentic and the inauthentic aspects. But this is not a true division; rather, inauthenticity is the mode of lived experience of the authentic manifestation of Dasein’s existentials. Discourse is still discourse, but the experience of discourse differs from its fundamental ontological function in Dasein’s phenomenology. Yet against this, Lacan’s implementation of the cut entails a third term, the experience – or covering up or coping with – the cut itself. Thus, the splitting of language through the metaphor and the father entails triads, such in as the Oedipus complex itself as well as the Real-Symbolic-Imaginary triad. Thus, not only do Dasein and $ differ by their handling of the cut within themselves and within language (or not), but the split or gap opened by a cut (i.e. the function of the cut) differs: Dasein does not experience the cut, this third term, whereas the barred subject does.

In the absence of any positive deconstructionist theory of the subject the significance of the comparison of Dasein and Lacan’s subject, $, becomes clear. Derrida and those in his wake restrict themselves to poignant critiques of previous theories of subjectivity, but Heidegger’s Dasein and the subjectivity Lacan develops in Formations of the Unconscious out of Freud’s Oedipal theory do provide positive formulations of radically new subjectivities that can incorporate and live or function while still incorporating internal, structural splittings. For both Dasein and $, language is shifted to the interior of the subject and made constitutive of the subject. Moreover, these subjects become historically determined. And with the incorporation of these new structural complications, both Dasein and Lacan’s development of Freud’s Oedipal subject came to bear a new and improved verisimilitude to the human being, they were approximating. This verisimilitude of the model to its study is achieved largely through an acceptance and then integration of the cut within the subject. In this way it becomes clear that the more cuts and splits are integrated structurally into models of the subject, and not ignored or forcibly closed, the more closely this model will approximate the subjectivity and experience of the human being. This will entail, too, a more accurate epistemology and a better understanding of consciousness, its knowledge, and the mind.

Notes

Works Cited

Derrida, Jacques. Heidegger: The Question of Being & History. Translated by Geoffrey Bennington. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016. Print.

Descartes, René. “Meditations on First Philosophy.” The Philosophical Works of Descartes, vol. I. Translated by Elizabeth Haldane and G. Ross. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1967. 131-199. Print.

Heidegger, Martin. Being and Time. Translated by Joan Stambaugh. Albany: SUNY Press, 2010. Print.

---. Being and Time. Translated by John Macquarrie and Edward Robinson. New York: Harper Perennial, 1962. Print.

Lacan, Jacques. Seminar V: Formations of the Unconscious (1957-1958). Translated by Russell Grigg. Cambridge: Polity, 2017. Print.

---. Seminar XI: The Four Fundemental Concepts of Psychoanalysis (1964-1965). Translated by Alan Sheridan. New York: Norton, 1977. Print.

Nobus, Danny, and Malcolm Quinn. Knowing Nothing, Staying Stupid: Elements for a Psychoanalytic Epistemology. London: Routledge, 2005. Print

Eric VanLieshout

Ph.D. Candidate, SUNY Buffalo

ericvanl@buffalo.edu

© Eric VanLieshout 2018