The Anthropocene Memorial: Recording Climate Change on The Banks of the Potomac River in Washington D.C

Clara de Massol de Rebetz

Longitudinal Section of Climate Chronograph © Azimuth Land Craft [1]

Sense of Place / Sense of Time

This article explores the temporal qualities of the Anthropocene from the perspective of memory studies. It examines how thinking memory at a time of ecological catastrophes can make sense of the paradigm shifts entailed by the new geological era. In the last decade, environmental debates crystallised around the contentious concept of the Anthropocene, a term coined by Paul Crutzen and Eugene Stoermer in 2000. The Anthropocene refers to the geological epoch superseding the Holocene, in which human activity on the planet has become the main geological force. As the Anthropocene refers to geological time, it is intrinsically linked to memory. Lucy Bond, Ben De Bruyn and Jessica Rapson (2018) explore the possibility of planetary memory in the Anthropocene:

[b]y registering the literary inscription of individual and collective memories of climate change experience alongside the growing archive of vanishing landscapes and species that characterise the nonhuman universe of the Anthropocene, the notion of planetary memory enables us to join macro-, meso- and microscopic perspectives (Bond, De Bruyn and Rapson 7).

A memory studies perspective on the Anthropocene could thus enable an exploration of the temporal, material, epistemological and representation specificities of the new epoch.

The article argues that remembering in the Anthropocene is registering planetary extinction and transformation, without obliterating the importance of locality and specificity. A planetary memory of the Anthropocene would thus be about understanding and recording the differential violence caused by climate change and human-made ecological catastrophes on different human cultures, non-humans life forms and non-biological matter all over the globe. Memory in the Anthropocene is therefore not only legible through human archives but also through non-human traces of extinction – flood lines and drowned islands, extinct species and future fossils, CO2 levels in the atmosphere and plastic particles contaminating bodies and landscapes. Planetary memory is accessible through what is destroyed and what remains, what has been inscribed in the air, into the rocks, the soils, the bodies of living things and deep into the oceans. Through an examination of Climate Chronograph, a climate change memorial project, this article thus investigates how a planetary memory of the Anthropocene can be conceptualised at a time of climate change.

Climate Chronograph is a climate change memorial project designed by architects Erik Jensen and Rebecca Sunter from Azimuth Land Craft, an Oakland based architectural firm. It was the Memorial for the Future competition winner, a competition organised by the United States National Park service, the National Capital Planning commission and the Van Alen Institute in September 2016. The proposed memorial is to be located on the banks of the Potomac river, in the Washington D.C. national park, adjacent to the National Mall. A slopped park of cherry trees would gradually be submerged in the rising river creating a physical and visual record of rising sea levels. Climate Chronograph is a melancholic memorial recording the rising seas and the disappearance of coasts and floodplains in the present. The memorial brings attention to the slow but devastating changes induced by anthropogenic climate change. Row by row, the perfectly aligned cherry trees would slowly sink in the rising river creating a harrowing timeline of climate change, a macabre cortege of a once blooming park.

Even if humans have throughout history shown the capacity to adapt to new environments and travel long distances, ultimately humans seek what Anthony Giddens refers as ‘ontological security’ (Giddens 243), a societal sense of continuity and anchoring in space and time. Lucy Bond and Jessica Rapson in turn demonstrate that even if memory and space are subject to social, political, environmental and cultural changes, it is via these mobile structures that societies construct time, understand the past and envision the future. As historian Pierre Nora and sociologist Maurice Halbwachs demonstrate, specific sites can then become repositories of collective identity whilst memory is socially conditioned and constructed. Whether it is displaced populations of low-lying islands or continental populations not recognising their surrounding as it gets irreversibly hotter, drier, colder or wetter, with climate change, human senses of ontological security, collective identity and memory are threatened.

The site of Climate Chronograph was chosen by Sunter and Jensen because of its proximity to the Washington D.C. National Mall. With its many memorials and museums, the National Mall is a commemorative hub, a fundamental place for the construction and assertion of a multi-layered national identity in its tension and diversity; making the city one of the most important civic and public space for the people of the United States. Climate Chronograph was also originally designed to be located on a human-made island, the East Potomac Park, in the Potomac river, adjacent to the National Mall, thus enjoying the symbolic aura of the other memorials as well as being located on a land that has been sinking for decades. According to Climate Central Projects,[2] Washington D.C. is likely to see record flooding by 2040, only three feet of sea level rise would drown the national park, with the worst NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) prediction at twelve feet level rise by the next century.[3] Climate Chronograph’s slop was then calibrated in such a way that one row of trees would drown every ten years.

The memorial self-reflexively engages its audience with the alteration and instability of their surroundings therefore linking the Potomac river to the planet, extending the framework beyond borders, while recognising the importance of locality. The architects in their competition report explain: “Transformation of the memorial mirrors transformation in the world, and bears witness to the changes wrought on a landscape over time.” (Sunter and Jensen 34) Climate Chronograph gives us an opportunity to explore how commemorative spaces could look like in an age where land space is increasingly restricted. But after the 2016 election, the architects responsible for the project have abandoned the idea of building the memorial in Washington DC, on their website they explain seeking a new tidal site for Climate Chronograph. It opens up the question of the site specificity of prospective climate change memorials. The framework is to be extended beyond borders since climate change is a planetary phenomenon, but the importance of locality still needs to be recognised. In her 2011 essay Susannah Radstone argues for the locatedness of memory, she states that “memory is always located, it is […] specific to its site of production and practice.” (Radstone 113-114) Radstone reasserts the locatedness of memory within a transnational and transcultural context, which does not mean in the case of climate change memorials a negation of the transcultural and planetary magnitude of climate change but reiterates the importance of locality.

In June 2018, during an interview conducted by the author,[4] the architects talked about the possibility of a different site and alternative design. They take the example of Polynesia, sinking under rising waters:

Eric Jensen: The idea of the very powerful, formal grid maybe doesn’t have the same connotation culturally in Polynesia and perhaps the kind of things that Climate Chronograph is trying to teach the rugged individualist of America to accept about vulnerability and change, these are sorts of things that might be culturally more developed in other societies. And the idea of memorialisation would be its own kind of question. What is memorialisation when a place has been a victim of colonial and postcolonial oppression for hundreds of years? Those are the kind of question that Climate Chronograph brings into existence as a new memorial for the Anthropocene.

Rebecca Sunter: If it were to be proliferated, Climate Chronograph could functionally be a living observatory wherever it would be, but it would require a very site-specific thinking, something that wasn’t just importing an old scheme, but something that were very much more about spending time with the people and begin to understand another culture, land stewardship, land management or land relationship that those people have and then expressing that with the memorial.

Visitors of Climate Chronograph are exposed to a planetary reality, the memorial is metonymical in epitomizing in one location what happens and will happen to the planet in the Anthropocene. The drowned Climate Chronograph will not be the only climate change memorial, the whole planet will. It is therefore necessary to keep in mind the dialectic movement that broadens local to global which still in cases restrict global to local.

Climate Chronograph is site specific but it is also time specific, it requires to think memory as moving through the past, present and future. During the interview, Rebecca Sunter explained:

The memorial compresses time and expends time and it allows whoever visits to feel those two things simultaneously, and it’s almost uncomfortable and revelatory. At the same time, you are feeling the past that has created the situation that we are now, past the point of no return, and we are looking to the future of what that return is going to yield.

Climate Chronograph, in a Bergsonian temporal perspective, carries all of its past within its present, as it becomes its future. French philosopher Henri Bergson in Time and Free Will considers time as different from duration (la durée), which is conceptualised as mobile and unfinished, always becoming. This incompleteness renders the past active in the present via memory. The present for Bergson is the record (traces) of what we are ceasing to be as well as, and without contradiction, the seed of our becoming. To understand memory is to recognise that experiences are juxtaposed, so a past moment is continuous with a present moment, memory is thus the expansion of the past in the present. In Matter and Memory, Bergson also considers memory as mobile. Nik Wakefield explains:

For Bergson memory is an action, not a storage house. Memory is knowing what might be done. This implies that the past is integrated with the present as opposed to an idea of memory as isolated from experience. Memory is an aspect of experience. […] Each new moment carries previous moments within it. (Wakefield 164)

Memory is not stored and fixed images of experiences; the present contains imprints of the past and those imprints are changing as time is moving. Climate Chronograph encompasses its past, present and future: it records past and present flood lines and foresees its future drowning. In that sense, it is a Bergsonian memorial, a way for the visitor to access the past and the future past through the present.

Bird’s-eye view of Climate Chronograph @ Azimuth Land Craft

Counter-Memorial Practices and The Unrepresentability Of Climate Change

Climate Chronograph’s architects do not seek to preserve the memory of what is being lost to planetary climate change. Instead they invite viewers to contemplate decay, the memorial is anchored in the present to reflect on the drowning and overall mutation imposed to matter in the Anthropocene. In that sense, Climate Chronograph could be seen as a counter monument, what James E. Young defines as “a monument against itself” (Young 267). Climate Chronograph is designed against the traditionally perennial function of memorials, it is active, it progressively and unrelentingly represents and embodies the past and the future in the present. In their report Erik Jensen and Rebecca Sunter write: “The built work is a pastoral meditation offering a counterpoint to the heavily constructed National Mall.” (Jensen and Sunter 21) Climate Chronograph is a memorial against the stone and iron of the National Mall memorials, instead it presents a slow drowning of organic and decaying material, focusing on grief and contemplation over preservation, on transformation over constancy. Like Jochen Gerz and Esther Shalev Gerz’s Monument Against Fascism, that slowly sunk into the ground of the city of Hamburg from 1986 to 1993,[5] Climate Chronograph acts upon its own destruction and disappearance.

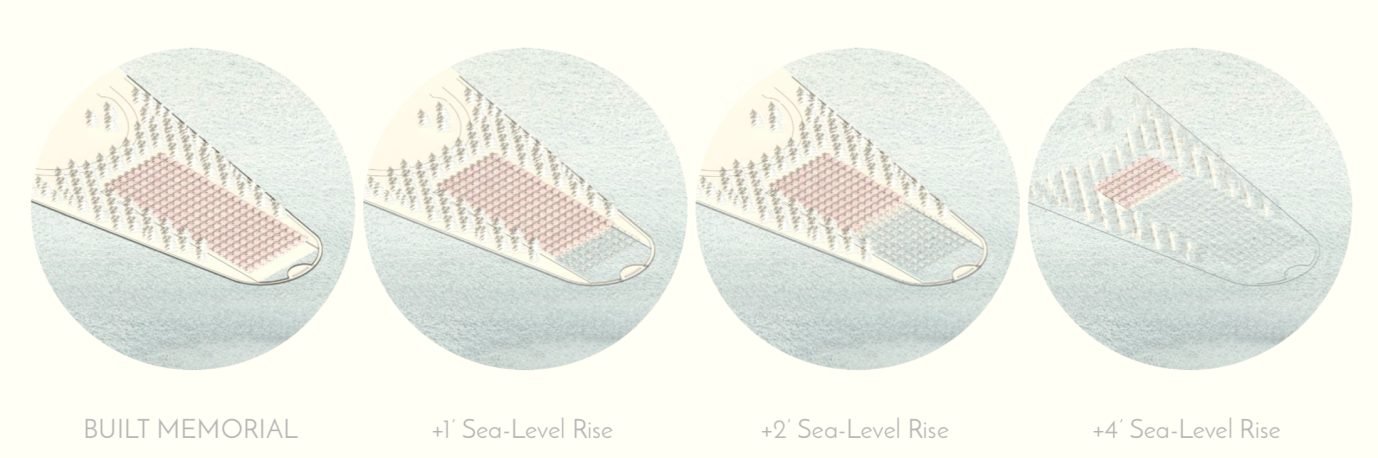

The evolution of Climate Chronograph @ Azimuth Land Craft

Further in their report, Sunter and Jensen specify: “The memorial represents a counter narrative in a society where techno-utopianism assumes the future will be solved the same as the past.” (Sunter and Jensen 33) Climate Chronograph is built in opposition to neoliberal and ‘techno-utopianist’ hegemonic ideas regulating state and public discussions. In that sense, the memorial inherits from a tradition of counter memorial practices.

In his 1971’s essay “Nietzsche, Genealogy, History” Michel Foucault develops his rejection of institutionalised history by conceptualising the idea of a ‘countermemory’. The French philosopher defends the use of images and archives rejected by the state and propose their inclusion into an alternative narrative and countermemory to achieve “a transformation of history into a totally different form of time.” (Foucault 93) Countermemory is thus ontologically differential and critical. But it is not until Young’s ‘counter-monument’ that the idea of an alternative form of memory-making is embraced in memorial practices, art and architecture. Young’s counter-monuments are “brazen, painfully self-conscious memorial spaces conceived to challenge the very premises of their being.” (Young 271). Veronica Tello explains: “[t]he counter-monument is not a means of burying the past [or in this case, drowning it], but rather a process of prefiguring the thickness of history and brutality, and of counting disagreement as part of the process of remembrance, rather than trying to cover over it.” (Tello 22) Climate Chronograph does not resolve climate change but it exposes the material reality of it. The memorial records in a public space, the transformation and violence of climate change and reveals the ‘thickness’ of time, the interconnection between past, present and future.

Similar to German artists and architects who, in a postmodernist reaction to monumentality, opposed monumental forms as representative of Nazi aesthetics, Sunter and Jensen design a counter-memorial in response to ‘techno-utopianism’ and political climate scepticism. Like Jochen Gerz and Esther Shalev Gerz’s Monument Against Fascism, Climate Chronograph is a monument ‘against itself’; by defining themselves through their disappearance rather than their perenniality, the Gerz’s monument and Climate Chronograph both tell a story of decay and regeneration. Climate Chronograph, after being erected from a land that only 100 years ago did not exist (the park on which it would sit is a human-made island), will sink back into the river bed. The memorial suggests an alternative way to see loss in the Anthropocene in which disappearance can be generative of a different manner to see time, memory and the planet.

Counter-memorials are defined by their disruptiveness, but over the years, the idea of counter-memorials in architectural and memorial discourses became more and more institutionalised, less about formulating an opposition to hegemonic narratives than about recreating an effective aesthetic strategy. And still, what mainly defines Climate Chronograph as a counter-memorial is its subject. As Young reflects, memorials are conventionally built after an event, to celebrate a personality, ideology, commemorate a conflict or mourn and remember collectively, to reflect on the cultural identity of a group at the time of the construction. Anthropogenic climate change exposes the past, as an intrinsic component of the Anthropocene, a result of industrial capitalism and human hubris, but its effects are felt in the present and yet to be fully felt in the future. Furthermore, climate change’s existence is still refuted by a minority – but powerful – group of political and economic leaders. As a counter-memorial, Climate Chronograph disrupts climate denialist and sceptic narratives as well as invites visitors to reassess their understanding of climate change, not as a phenomenon of the future, belonging to dystopias, disaster films or cli-fis, but as a disruption of the past and the present. The main obstacle to Climate Chronograph is thus its realisation, because of the memory it refers to. As the Anthropocene disrupts Holocene-age belief that human history is distinct from geological time, anthropocenic memorials anchor themselves within a proleptic temporality, containing human and planetary past, present and future. Maybe Climate Chronograph is then not solely to be understood as a counter-memorial but also as one of the first memorial of the Anthropocene. It is constructed in reaction to political hegemonic structures, to challenge visitors’ assumptions but it is also one of the first of its kind, one of the first of many drowned memorials.

Climate Chronograph in its potential disappearance and current inexistence also inherits post-war monuments’ commitment to represent the unrepresentable. From Adorno’s invective that poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric to Lanzmann 2004’s appeal to prohibit archival images of concentration camp, post-war countermonuments explore alternative representational strategies in which disappearances and absences are used as aesthetic and heuristic approaches. Climate Chronograph is the inheritor of that discursive practice to attempt to represent the unpresentable. Climate change’s unrepresentability take its roots in its temporality and its ‘slow violence’. Rob Nixon defines slow violence as “a violence that occurs out of sight, a violence of delayed destruction that is dispersed across time and space, an attritional violence that is typically not viewed as violence at all.” (Nixon 2) Slow violence is an unspectacular and insidious violence that bypasses human lifespan. Sea-level rise is slow violence: an ecological catastrophe whose destruction span generations. Climate Chronograph brings the violence of climate change in sight, the destruction is not dispersed but concentrated in one site, and the degree of violence is tangible, recorded in public space. Climate change, like the spectacles of immediate violence, becomes an image, a referent.

Jacques Rancière, in his writing on images reflects on and rejects the ‘unrepresentable’: to claim unrepresentability is to choose to ignore the event altogether. The French philosopher writes: “nothing is unrepresentable as a property of the event. There are simply choices.” (Rancière 129) Rancière’ rejection of a total inability to represent suggests the ability of artists and writers to overcome the challenges of the ‘unrepresentable’. Jensen and Sunter engage with the slow violence of climate change but they do not shy away from it. The architects adapt their representational strategy to the temporal and spatial qualities of anthropogenic climate change and demand that their visitor revise their modes of viewing to the particular scalarity of the Anthropocene. During the interview, Rebecca Sunter compares her project with Maya Lin’s Vietnam Memorial: a piece “inscribing a scar on the earth, as a repository for the collective pain, sorrow, guilt, and regret. [Lin] gave a public, civic place for these things to be held and shared, likewise, Climate Chronograph spatialises the fear, the anxiety, the guilt and optimism.” With Climate Chronograph there seems to be a sense of embracing the so-called unrepresentability of trauma and climate change, making the slow decay of rising seas visible and using that visibility to oppose denialist and apathetic institutional narratives.

But for now, Climate Chronograph, like many representations of climate change, is only an idea, an imagined memorial that exists on paper but remain within speculative and imaginative realms. Its non-actuality is central because it reveals the inexistence of climate change discussion and action at international and institutional levels. In that sense, it is not yet a counter-memorial because it does not counter any narrative, oppressive structure, hegemonic ideas in reality. To some extent, Climate Chronograph is only an illusion, a sentimental and romantic fantasy of a self-critical society, in tune with ‘nature’, and willing to inscribe in public space the destructiveness of anthropogenic climate change. The memorial would then suggest that before climate change, before human damaging ‘interventions’ on the land, there existed some kind of harmonious and peaceful ‘nature’. This nostalgic fantasy relies on an anthropocentric and emotional aestheticisation of the environment. In the context of climate change, Climate Chronograph, along with any natural landscape, is then presented as an endangered and weak structure subjected to human hubristic deeds. In that sense, it is not solely a prospective counter-memorial but also a memorial of the Anthropocene era, exploring and epitomising the relationships between humans and the land they live and die in.

Climate Chronograph: The First Memorial of the Anthropocene?

The Anthropocene thesis, as reasserting the ascendancy of humans over their surroundings, maintains the age-old dualism of nature versus culture, and reinstates the human species as the exceptional species. But this anthropocentrism has been opposed by environmental humanities scholar (Morton, Haraway): the Anthropocene thesis or its alternatives (Haraway’s chthulucene, or Hornborg’s technocene) also epitomizes posthuman and planetary debates that uphold interconnection over human exceptionalism. As Timothy Morton discusses, nature is a social construct, thinking the Anthropocene permits a conceptualisation of humans as embedded within planetary ecosystems, not separated from them. Climate Chronograph articulates the paradoxical anthropocentrism of the Anthropocene and can be thought as a heuristic device that allows for an exploration of the theoretical and material implications of climate change and the Anthropocene.

The memorial was originally designed to be located in Washington D.C., on Hans Point in the East Potomac Park. The park, managed by the National Park Service, is situated on a human-made island that only a century ago did not exist. It was completed in 1917 by the United States Army’s Corps of Topographical Engineers as a way to control the Potomac river’s frequent floods. From 1881 to 1917, the corps dug a large channel in the river to raise the banks and create an island, now the East Potomac Park. Climate Chronograph was designed to be built on this human-made island as epitomizing anthropogenic impact on the planet as well as exposing the kinship between different and complementary forces: climate change, tides and human engineering.

From 1915 to 1916, the corps planted three hundred thirty-six Japanese cherry trees that were gifted to Washington D.C. by Mayor Yukio Ozaki of Tokyo. Since then, people have been celebrating the popular Cherry Blossom Festival each spring in the streets of the city. Thomas Bender argues that the cherry trees have become part of the cultural history of Washington D.C. and its inhabitants and thus operate as identity and pride markers for the capital city. Ann McClellan in turn explores how the trees, initially a diplomatic gesture to mark the friendship between the United States and Japan, progressively became an integral part of the capital city’s identity. Climate Chronograph, made of rows of cherry trees, acknowledges that heritage and links itself to its city’s history. By using cherry trees for their memorial, Erik Jensen and Rebecca Sunter, would have inscribed Climate Chronograph within the cultural and civic history of the capital. In that sense, the architects’ aim was to include climate change discussion in the country’s memorial landscape, making the rising seas a paramount national concern.

The human-made East Potomac Park was created from the Potomac river’s soil, from its rocks, clay and sediments. The geologic history of the river and its area is thus contained within the park’s strata. The memorial’s cherry trees would then feed and grow from the river and its sedimental composition. Climate Chronograph thus juxtaposes human histories – from early twentieth century diplomacy to twenty first century climatic and political concerns – and geological time – from the creation of the Potomac river to the slow drowning of the East Potomac park and island. Memory is not only visible through the gradual sinking of the memorial, but also in the park’s biodiversity and geologic composition. The island itself encloses human and planetary histories making it a fitting site of memory in the Anthropocene. Climate Chronograph in Washington D.C., would give its visitors an immersive experience, intensifying their corporeal and psychological affectiveness with climate change and with the planet.

The memorial in visualising climate change and exposing the inhuman temporality of the Anthropocene, would allow its visitor to experience and witness the devastation, to anchor herself in human and inhuman time. In their report, Sunter and Jensen explain:

Climate Chronograph is slow, offering us an opportunity to shift our current, accelerationist thinking into a longer multi-generational time frame. Locals may witness a gradual progression of rising seas, whereas out-of-town visitors may never experience the same memorial twice. Imagine a young American’s staple eighth-grade trip to Washington, D.C.: one row of inundated trees. During a college protest: three flooded rows. When she returns later in life with her children: seven rows of rampikes. (Jensen and Sunter 34)

The architects tell the story of Climate Chronograph through its imagined visitors, envisioning time passing, generations succeeding and the memorial transforming with them. These simultaneous movements create an affective proximity between the visitor and the memorial and between humans and the planet. Climate Chronograph tells the story of human history, geological time and personal memory together, as interconnected with the movements of floods and decay, with the movements of the Anthropocene.

In ‘Time Matters’, Elizabeth Grosz, Heather Davis and Etienne Turpin, place architecture “as the ‘first art’, in Deleuze’s sense, as the marking of a territory that temporarily and provisionally allows chaos to slow enough for new intensities to be felt and emerge.” (Grosz, Davis and Turpin 129) The slowness of climate change, as well as its disruption, are imprinted on the land so that they become legible. Architecture, and in this case, memorials, are framing devices that allow visitors to experience and comprehend a temporality (geological time) and force (climate change) exceeding human existence.

By imagining the future memory of a visitor, the architects imagine the future memory of climate change, thus situating the Anthropocene within a non-linear history, in which past, present and future are juxtaposed. Climate Chronograph by recording the movements of climate change would allow its visitors to feel the movements and the temporality of the Anthropocene. In that sense, Climate Chronograph is a planetary memorial of the Anthropocene displaying climate change and extinction and creating affects between living and non-living entities.

Through its disappearance and vulnerability, the memorial opens up a space to experience the Anthropocene collectively, and to feel an interconnectedness between humans, river, tides, and trees. The drowned memorial is not a negative space but the sign of an absence, or rather, the sign of a devastating transformation and maybe regeneration, Sunter expounds: “as any ecological disruption, like a massive fire, climate change is a very violent event on the landscape but at the same time it opens new ecologies and fertilisation for a new order.” The memorial would exist in the memory of its presence as well as beneath the river, decaying in the planetary rising waters. The memorial could then become a site of healing and fertilisation, a place to contemplate loss and witness the emergence of a new sustainable order.

However, this idea of affective proximity, sustainability and healing can be perceived as romantic, ineffective and illusory. It involves anticipating and imagining the effects of a somewhat unpredictable and slow-moving process. It is also precarious to attempt to imagine a healed and fertile faraway future, past climate change and past Anthropocene, while the present effects of global warming are displacing entire populations. Because for now the memorial remains within the realms of speculative hopefulness; Climate Chronograph in its nonexistence does not achieve the healing and interconnection promised, it might acknowledge such possible interconnections, but it would be indulgent to only rely on the imagination and the aesthetic of decay to discuss a highly violent current phenomenon affecting populations all over the world.

Moreover, the memorial, as it sits in a long tradition of scientific measuring of weather events – in their report the architects mention the Nilometer[7] (Jensen and Sunter 6) as the ancestor of the memorial – is as much a site of mourning than a living observatory. The memorial, like the Nilometer, is calibrated to a high flood line, so even when the flood does not exceed the line, there would still be a reminder of its destructive potential. Climate Chronograph is designed as a future-oriented instrument of control as much as a way to explore human measuring, recording and regulating technologies, Jensen explains:

It’s about confronting the aesthetic of control. […] The memorial is not just going to be a collection of dead trees seating in some sort of neo classical formation, those trees […] are going to fall in the water in random ways, the decay of the grid is the new emergent formal logic of that site that harkens a new order, that aesthetic of a post anthopogenic era, or a post controlled era. It is much more about the decay of the old controlled-driven way and the emergent species that would exist at that liminal threshold.

The architects during the interview situate their memorial as opposing and exposing Enlightenment ideas of progress and control. As the memorial falls apart, it is the illusion of human control that is revealed. Jensen clarifies:

Grids of trees were once used to talk about the power of the Enlightenment and the idea of the infinite potential of humanity, the trees marching to the horizon with certainty and confidence. Now, what we are making is a sort of marching to the ultimate horizon, it’s the end of André’s[8] line […] You can look at the marching rows of trees that are still healthy, climbing up the slop in a similar fashion to that French landscape, imagine the ultimate potential and power of the earth and doing so, perhaps began to understand your own vulnerability, and actualise changes.

In marking the landscape with a chronograph, the architects assume responsibility for a future that is unknowable. The memorial is a site for future generations, it functions as a marker displaying how future past generations knew about the disruption. In that sense, it relies on its material instability to communicate a sense of responsibility. But the degree of decay is unknowable. The memorial also displays the unforeseeable material agencies of future drowned trees. In its ontological unpredictability, it exposes the limits of human control. The philosopher of science Myra J. Hird’s call for an “ethics of indeterminacy” (Hird 30) as a way to account for the unknowable nature of waste, is useful in thinking the indeterminacy of Climate Chronograph. Such ethics of indeterminacy evidences the antagonistic relation between instability and control expressed by Sunter as she cites another influence:

Boullée’s Cenotaph for Newton[9] was a big inspiration in terms of the grandeur, a eulogy for a time that we will be reckoning with for a long time. With somebody like Newton, it’s easy to elevate that and [Boullée] wanted to talk about the immutability, but for us coming to terms with our own human power […] Climate Chronograph is an inversion of Cenotaph for Newton, instead it’s speaking of the mutability and vulnerability of life, putting the hubris of the Anthropocene against its extreme fragility.

The memorial embodies both a human will to mark the landscape and regulate it as well as exhibits the failure of control.

But this idea of responsibility positions humans as stewards of the land, and to some degree contradicts the architect’s ecological ethos. Marking the planet with a chronograph reasserts the illusion of human control. Mike Hulme explains that climate and seasons are cultural and social constructions created to give humans the illusion of control, the illusion they can predict and regulate weather and weather events. Climate Chronograph, like climate, is a mental construction allowing humans to live with the weather and its destructive potential. Climate Chronograph, similarly to the Nilometer or the French grid gardens of the Enlightenment, is ultimately a self-reflexive control framing tool developed by Jensen and Sunter to survey and expose human’s destructive propensity to regulate the non-human.

Conclusions

Hains point and the East Potomac Park, where Climate Chronograph would have stood is situated less than three miles away from the National Mall and yet it feels far away. Contrary to the memorial hub of Downtown Washington, the park is quiet, only a few passersby are seen during the day, joggers and cyclists mostly. Climate Chronograph, if it had been built on that location, would have enjoyed the monumental aura of the nearby memorials as well as the tranquillity of a residential park. It would have been an urban memorial, where children play, where people learn to sail, meet and exercise, as well as a sacred site of contemplation and reflection. But Hains Point is only grass and trees. The memorial is not there and probably never will, not on this location anyway. And yet, if a visitor were to look closely, she might notice that the memorial already exists. It is in the flood lines on the grass, made of debris, sediments and plastic waste, it is in the mini swamps that punctuate the island and it is in the raised cement road, swollen and damaged because of water infiltration.

The river marks its movements on its own on the island; the non-existence of Climate Chronograph as a cultural and institutional memorial is significant but climate change and rising waters do not wait for federal clearance. Climate Chronograph will be seen, witnessed and experience by all who look and all who suffer and die because of sea level rise. The landscape of the United States is already one of drowned trees and flooded cities. In 2005, Hurricane Katrina devasted New Orleans and its surroundings. In 2017, Hurricane Harvey and its subsequent flooding cost $700m in damage to the city of Houston.[11] Areas such as south Louisiana do not have to wait for spectacular natural disasters to be submerged. The Isle de Jean Charles in Terrebonne Parish, Louisana, has been sinking for half a century. Its residents, the Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw tribe, had to take actions in their own hand because of a lack of government support. And still, today 98% of the island is under water.[12] Those drowned areas affect mostly working-class black communities and native American populations who are at the forefront of climate disasters and rising waters. Building Climate Chronograph in a capital city and a national park could bring climate change into existence in public and institutional discourses, it could thus prevent powers at play from looking away and it could situate climate change at the centre of civic and cultural life. But as the American government ignores the effects of climate change on its territory and population, it cannot support the construction of a climate change memorial. Climate Chronograph does not exist without climate change and climate change cannot exist without Climate Chronograph.

The memorial is designed to be beautiful, the cherry trees standing proud on the Potomac island, and drowning slowly in the rising river, their beauty serving a moral purpose, so that they become repositories for the pain and suffering of populations affected by climate change. But using the aesthetic of decay and ruins to discuss human-made environmental disaster is to some extent simplifying a complex reality. Climate Chronograph tells the story of fallen trees, embodying a belligerent and all-powerful nature taking back its power from hubristic human behaviours in an increasingly hot, wet and rotting planet. This narrative, in addition to supporting the age-old dichotomy nature vs humans, fails to acknowledge that populations, mostly poor, non-western and non-white, already suffer and die because of rising sea-levels. As Rosi Braidotti exposed in a UCL 2017 keynote lecture, the Anthropocene discussion sometimes creates the illusion that “we are all in this together”, that with the advent of climate change, a kind of planetary citizenship and solidarity is formed. But “we are not one and the same”, this seemingly planetary empathy conceals a neoliberal structure of differentiation and hierarchy. Although climate change is a planetary phenomenon affecting the physicality of the planet, it does not affect displaced populations of low-lying islands and indigenous territories the same way it affects continental populations in post-imperial cities. The idea that anthropogenic climate change is borderless fuels a universalist vision of the planet. Climate Chronograph in all its institutional and political potential seems to perpetuate western-centric discourses that positions climate change as a prospective phenomenon. But the site-specificity of the memorial as it was originally designed in Washington D.C. makes it western-centric, would it be built in a different location, it would epitomize the locatedness and specificity of that space while expressing the material and conceptual schisms of the Anthropocene at a planetary level. As it seems less and less likely that such memorial would be built anywhere on the planet, Climate Chronograph’s full potential remains sadly unknowable.