W.E.B Du Bois, B.R. Ambedkar and the History of Afro-Dalit Solidarity

Anindya Sekhar Purakayastha

O Truce of God!

And primal meeting of the Sons of Man,

Foreshadowing the union of the World!

From all the ends of earth we come!...

Mother of Dawn in the golden East,

Meets …

The mighty human rainbow of the world, …

So sit we all as one…

The Buddha walks with Christ!

And Al-Koran and Bible both be holy!...

We are but weak and wayward men,

Distraught alike with hatred and vainglory;…

We be blood-guilty! Lo, our hands be red!...

But here—here in the white Silence of the Dawn,

Before the Womb of Time,

With bowed hearts all flame and shame,

We face the birth-pangs of a world:

We hear the stifled cry of Nations all but born—

… We see the nakedness of Toil, the poverty of Wealth,

We know the Anarchy of Empire, and doleful Death of Life!

And hearing, seeing, knowing all, we cry:

Save us, World-Spirit, from our lesser selves!

Grant us that war and hatred cease,

Reveal our souls in every race and hue!

Help us, O Human God, in this Thy Truce,

To make Humanity divine!

- (Du Bois, Darkwaters 275-276)

Nationalism, a Means to an End. Labour’s creed is internationalism… Nationalism to Labour is only a means to an end. It is not an end in itself to which Labour can agree to sacrifice what it regards as the most essential principles of life. (Ambedkar, Writings and Speeches 3)

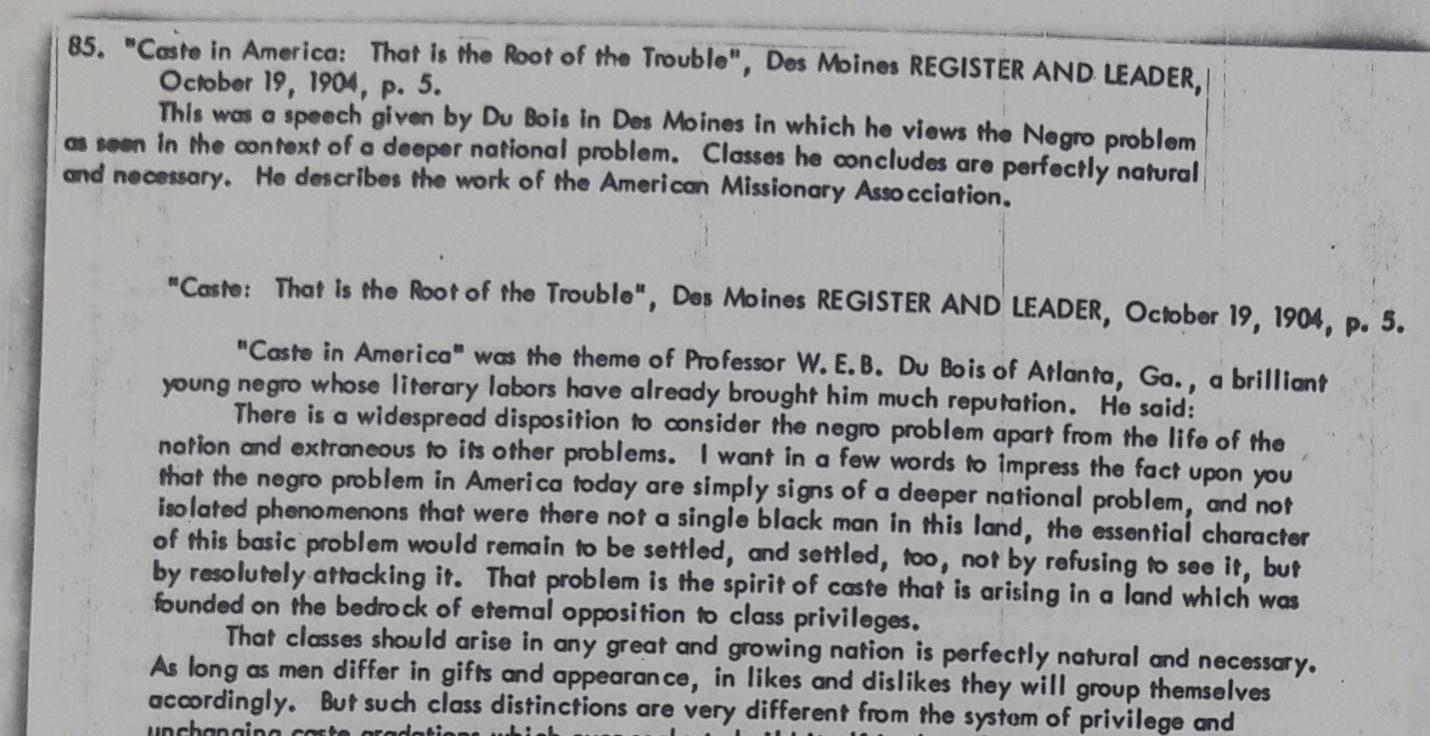

Way back on October 19, 1904, W. E. B. Du Bois, author of The Souls of Black Folk (1903) and one of the prime architects in the formation of the Niagara Movement and the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP, formed in 1909) in America delivered a lecture titled, “Caste: That Is the Root of the Trouble” and compared the “Negro problem” of America with the obnoxious system of caste –

… the Negro problem in America today are simply signs of a deeper national problem … that problem is the spirit of caste that is arising in a land which was founded on the bedrock of eternal opposition to class privileges. (Du Bois, 1904, Du Bois Archive, see image 1)

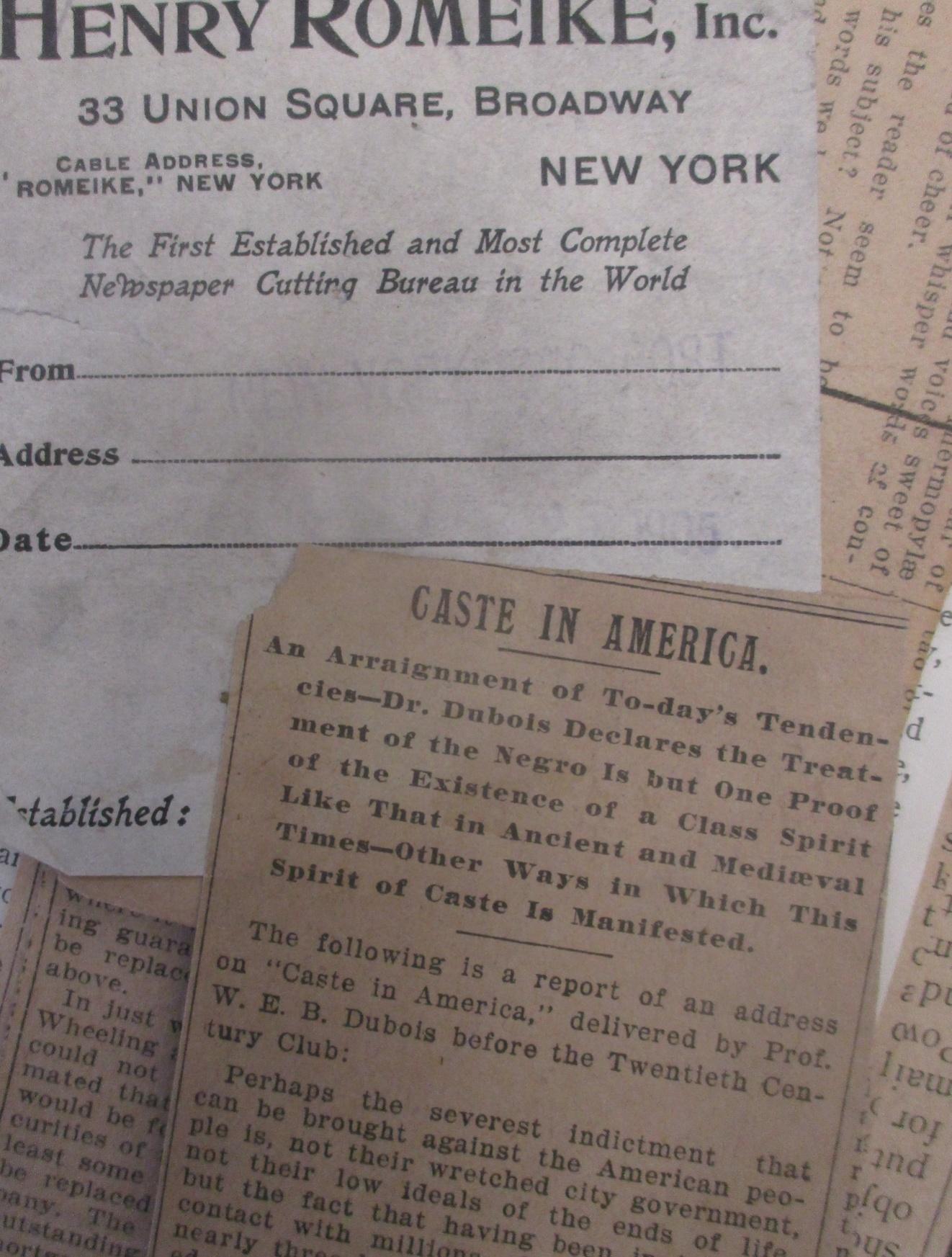

In a similar vein, rare archival records preserved in the Du Bois archive of the University of Massachusetts, Amherst showhow Justice Edward O Brown, Judge of an Appellate court in America in his address on “Race Discrimination” delivered at the fourth Annual Conference of NAACP at Handell Hall, also described American Jim Crowism as the problem of caste – “The white man is erecting the worst and meanest caste systems in his treatment of the negro …” (Reported in April 29, 1912, newspaper clippings, Du Bois Archive Box No: 252, see image 2). This conflation of Jim Crow American South with the obnoxious Brahminical Indian social system of caste is not at all surprising, and this substantiates how the pernicious practice of caste was abhorred by the international civil rights community. This eliding of racial segregation with caste atrocities paves the way for a common platform of Afro-Dalit solidarity. Two decades back, Vijay Prashad’s essay “Afro-Dalits of the Earth Unite” (2000) and subsequently a series of significant works such as “The Dalit Panthers: Race, Caste, and Black Power in India” in Nico Slate’s Black Power beyond Borders: The Global Dimensions of the Black Power Movement (2012); Gyanendra Pandey’s A History of Prejudice: Race, Caste and Difference in India and the United States (2013); Purbi Mehta’s doctoral work Recasting Caste: Histories of Dalit Transnationalism and the Internationalization of Caste Discrimination (2013); Manan Desai’s “Caste in Black and White: Dalit Identity and the Translation of African American Literature” (2015); Bacchetta, Maira & Winant’s Global Raciality: Empire, PostColoniality, DeColoniality, (2019); Afro-Asian Networks Research Collective’s “Manifesto: Networks of Decolonization in Asia and Africa” in Radical History Review, 131 (2018); Nico Slate’s Lord Cornwallis Is Dead: The Struggle for Democracy in the United States and India (2019) have consistently expressed identical views about common grounds for Dalit-Black affiliations to eradicate existing systems of social discrimination across the globe. The reigning leitmotif set by Du Bois about the “mighty human rainbow of the world” and the “union of the world” through the “World-Spirit” is reinforced through all these intersectional researches on “global raciality” or the idea of Black/Dalit/Minority power-beyond-borders.

The concluding stanza of the quoted poem at the beginning of this essay by W. E. B. Du Bois was read out in the opening session of the First Universal Race Congress, held in London, in 1911. Du Bois, according to newspaper reports, described the Universal Race Congress as some kind of Universal Grievances Committee, a body to address our collective human suffering and it is really interesting to note the striking cosmopolitan spirit expressed by Du Bois in this poem, an attribute that helps us to situate him along with Ambedkar in our efforts to understand the “mighty human rainbow of the world”- a constellation of shared sufferings and collective endeavour to annihilate all forms of divisions and plight. Both Ambedkar and Du Bois sculpted in their own constituencies a global ethics of equality and justice, categories that have universal implications. Du Bois talks of the “world spirit” and reiterates his dream of making “humanity divine”, plagued as it is within the cauldron of “war and hatred” premised on “race and hue”. This is a brilliant vision of equality, justice and end of violence because– “so sit we all as one”—a blueprint for an equal world, immensely revolutionary in its courage and vision, something akin to what Ambedkar attempted to do through his proposed constitutional overhauling of the Indian social discourse of caste stratification.

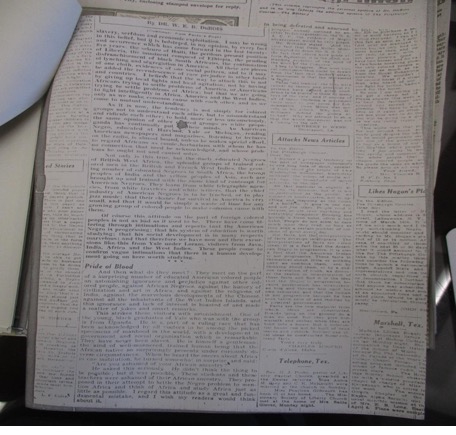

I shall come to this conjoined study of Du Bois and Ambedkar later, but let me clarify at the outset that this essay is not a simplistic comparative study of two thinkers hailing from two different continents and divergent social conditions. My attempt here is to argue for a common universal frame of analysis that, while acknowledging different contingencies ascribed to these two thinkers, also locates a coalitional juncture for unified struggle against injustice and exploitation. Such an intersectional optics of unified or shared resistance is necessary if, as Du Bois said, we are to transcend our narrow “lesser selves”, allowing the “womb of Time” to generate “the birth pangs of a world” free from the stigma of race, caste and xenophobia. Our combined analysis of the race-caste logic will help unpack new possibilities of cross-cultural optics for resistance – something that has immediate purchase for postcolonial theory and counter-hegemonic practices. W. E. B. Du Bois, Frantz Fanon, Aime Cesaire, B R Ambedkar, Edouard Glissant, Malcolm X – all form a rich constellation of radical thinking which needs to be engaged together as the colonized and the subjugated cannot be bracketed to a particular country, they are of the world and require global responses to minimise their plight. This essay identifies the overlaps of caste and race and other forms of segregation logic and recalls the long history of continental solidarity in forging a liberated future. Ina world engulfed as it is in rising trends of xenophobia, such internationalisation of anti-caste-race-minoritisation struggles hold promise. In what follows I attempt through certain archival material to reinforce the global root of such conjunctive cross-cultural fight against all forms of segregation and cruelties. Affinity based coalitions of fellow sufferers were constituted through years of Pan-African and decolonial movements, and it is theoretically productive to revisit that archive of common history of stratification and sufferings. In one of his regular columns written in early twentieth century in the Pittsburgh Courier, Du Bois painted all kinds of atrocities related to racial, colonial and other forms of coercion as “pieces of the same cloth”.

I may be wrong in this belief, but it is bolstered in my opinion, by every fact and occurrences…the seizure of Haiti…the pending disfranchisement of Black South Africans, the continuation of lynching and segregation in America…all these are pieces of the same cloth, evidences of one social pattern, and to it may be added the recrudescence of rare prejudices in other lands and countries. I believe that the way to attack this is not by giving up local fights and local agitation … not by having Africans trying to settle problems in America … but that we are going to fight … only as we make common cause with each other, and as we come to mutual understanding. (Du Bois, Year unknown, Du Bois Archive newspaper cuttings, see image 3)

The present essay tries to retrace this effort to “make common cause” with each other (fellow sufferers across the globe) because the genesis of Negro-hood or Dalit-hood/Minority-hood is tied to the same “social pattern” of White colonization/Brahminical/Hindu/Christian supremacy. This desire for making common cause prompted Ambedkar to narrativize the traumatized life-world of the Shudras, while Du Bois chronicled the strivings of the Souls of Black Folks – both could weave the universal ethos of egalitarianism and social endosmosis because both would capture centuries of historic crimes against humanity, and both pledged to unmake the dark tradition of segregational butchery by asserting what the American newspaper Public Opinion wrote quoting Walt Whitman, while reporting the motto of the First Universal Race Congress held in 1911 in London--

Each of us inevitable,

Each of us limitless – each of us with

His or her right upon the earth

Each of us allowed the eternal purports

Of the earth

Each of us here, as divinely

As any are here

(Public Opinion front page report, ed. Percy L Parker, July 21, 1911)

This reads like a remarkable treatise of universal equality and one immediately remembers Ambedkar’s memorable words in this context.

In other words there must be social endosmosis. This is fraternity, which is only another name for democracy. Democracy is not merely a form of government. It is primarily a mode of associated living, of conjoint communicated experience. It is essentially an attitude of respect and reverence towards fellow men. (Annihilation of Caste 260)

This faith in the “inevitability” of each and every one in the “eternal purport of the earth” drives one to believe in this spirit of democratic fraternity, equality and social endosmosis, and when Du Bois in The Souls of Black Folk made his famous observation that “the problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color-line” (32) he was also similarly registering his voice for a world that defies the “color-line” of injustice that makes one inquire “why did God make me an outcast and a stranger in my own house?” (Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk 8). Du Bois’ profound social analysis made us realise that

… the Negro is a sort of seventh son, born with a veil, and gifted with second sight in this American world, - a world which yields him no true self-consciousness, but only lets himself through the revelation of the other world … this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of the others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of the world that looks in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his two-ness… (Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk 8)

Any perceptive reader does not fail to recall here Ambedkar’s description of caste in analogical fashion, as what Arundhati Roy identifies in the introduction to Ambedkar’s Annihilation of Caste as an “endogamous unit”, an “enclosed class” or as a system with “ascending scale of reverence and a descending scale of contempt” (24). When young B R Ambedkar arrived in New York City in 1913 to attend Columbia University, America was already experiencing massive organized resistance to racial persecution. Booker T. Washington and Frederick Douglass, the two noted Black leaders were very well known by then for their contribution in the project of “Black Reconstruction” after the abolition of slavery. The American Negro Academy was already established in 1897 with active participation of W. E. B. Du Bois in its formation and functioning. Du Bois began his famous Atlanta University Studies series on American Jim Crowism between 1898 and 1914 and published in 1899 his The Philadelphia Negro, taken to be the first sociological study of real conditions of Black Lives in Jim Crowe America. 1903 saw the landmark publication of Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk and the National Negro Committee which were the precursors of the NAACP. All these historical timelines and facts underscore the climate of organized protest and reigning episteme of liberation that must have nourished Ambedkar during his American days. As no concrete documents are available except the writings of Eleanor Zelliot (Ambedkar Abroad) on Ambedkar’s exact indebtedness to Western ideas and practices, it would be a productive exercise to explore further on this domain for new findings in Ambedkar studies. Zelliot while dwelling on Ambedkar’s indebtedness to his Professors in Columbia University, did merely mention about Ambedkar’s correspondence with W. E. B. Du Bois, but she did not deem it fit to elaborate further on Du Bois’s influence on Ambedkar or on Ambedkar’s knowledge of and connection with the larger civil rights movement happening during his student days in America. There has been a very recent work on thinking race and caste with W. E. B. Du Bois and Rabindranath Tagore (Goyal) and although Homi K Bhabha thought of working on Ambedkar’s “knowledge of the world” through a comparative study of Ambedkar and Du Bois, we are yet to see that work to come out (Zelliot). Bhabha’s critical reading of Du Bois’s novel Dark Princes both in his introduction to the Oxford edition of this text and also in his treatise on “Global Minoritarian Culture” strike the right note of globality in terms of minoritisation, Being-Blackness, or enforced-dalitness, etc

… Racial conflicts, straited selves, barrier between bodies and spaces – these signatures of segregation and separation also enforce an ethical proximity and a political contiguity in between social and cultural differences … (Bhabha 184-185)

In a similar vein, Bhabha also decodes the deeply embedded cosmopolitan spirit of Du Bois’s Dark Princess which has a strong Indian connection, and articulates the “cosmopolitan fantasy of a romance between like‐minded revolutionaries across divides of nation, ethnicity, class, and gender…” (Alston 19-20). In this article I am trying to locate the ‘political contiguity’ and ‘ethical proximity’ between the world views of Du Bois and Ambedkar as that has significant implications on future global democratic struggles for human rights and human dignity. One may recall here the 2001 Durban Human Rights Conference organised by the United Nations in which Dalit organisations from India attempted to register their grievances on continuation of caste atrocities in India, demanding the international bodies to treat the case as equivalent to racial discrimination – “caste and caste-based discriminations should come within the purview of the International Convention for Elimination of Race, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance.” (Visvanathan 2513).

The Durban petition incident immediately takes us to 1946 when Ambedkar wrote to Du Bois with virtually similar pleas and argument. On his return to India after the completion of his studies, Ambedkar’s role and contribution in sculpting constitutional policies are already well documented. His monumental writings and debates on individual rights, social justice, activism and legislative policy measures to be adopted in independent India made him one of the towering political thinkers of modern India and also of the world. Any research on Ambedkar necessarily engages with possible lineages of political thoughts or bodies of democratic ideologies that he must have been exposed to in his formative days in America as a scholar in Columbia University. His proximity to Harlem during his years of study at Columbia also motivates us to speculate further about his experience of civil rights protest in the U.S. In other words, one may inquire on how formative and influential was his New York years on his future role as a social crusader and a political thinker. The impact of his mentors John Dewey, Edwin Seligman, James Shotwell, and James Harvey whom he met and engaged directly in the U.S has already been recognized by all Ambedkar scholars, but there is a need to explore further his experience of witnessing anti-Black racism in America and this necessarily implies whether such personal witnessing of racial discrimination in America made him draw the underlying analogy of corresponding systems of caste stratification in India.

There is in other words, a dearth of scholarship on Ambedkar’s impression of racism and its bearing on his politics of the annihilation of caste. The W.E.B. Du Bois archive at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst contains a single item of correspondence between Du Bois and Ambedkar and this exchange of letters between them is already in the public domain but in this paper, I want to take the convergence of these two great minds of twentieth century world beyond the act of letter exchanging. I would argue that the future of Ambedkar scholarship and the postcolonial understanding of Du Bois, Ambedkar or Pan-Africanism or decoloniality require a thorough and conjunctive study of Ambedkar and Du Bois. The University of Massachusetts Du Bois archive records show that Ambedkar wrote to Du Bois in July 1946 to inquire about the National Negro Congress petition to the United Nations, signed and submitted by the NAACP to the UN to demand minority rights for the Blacks in America. Ambedkar in his letter to Du Bois mentions that he had been a “student of the Negro problem” and that “[t]here is so much similarity between the position of the Untouchables in India and of the position of the Negroes in America that the study of the latter is not only natural but necessary.” In his reply Du Bois wrote back in a letter dated July 31, 1946 by telling Ambedkar he was familiar with his name, and that he had “every sympathy with the Untouchables of India.” In what follows I would revisit this political and ideological proximity between these two thinkers.

SLP06013A. W. E. B. Du Bois 1904 Speech on ‘Caste in America’, Courtesy, Du Bois Archive, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Photograph © Author

SLP06013B. Newspaper clippings on caste in America, date unknown, Courtesy, Du Bois Archive, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Photograph © Author

SLP06013C. Du Bois’ article in The Pittsburgh Courier where he describes all oppressions as ‘pieces of the same cloth’, courtesy, Du Bois Archive, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Photograph © Author

Where the Dreams Cross: Conjoined Reading of Ambedkar and Du Bois

Ambedkar was the first Dalit to get a fellowship to study in Columbia University and Du Bois was the first African American to get a degree from Harvard. Du Bois went to Humboldt University to pursue his second degree and Ambedkar went to London School of Economics for his second stint in higher studies. Du Bois on his return had problems in getting a job in all white American universities and ultimately spent his entire teaching career in Atlanta University which was and till today remains to be a university for colored students. Du Bois struggled while hunting for a job and helped in the formation of various movements and association for the Blacks. His meticulous sociological study of Negro life was published in his The Philadelphia Negro. This is considered the first sociological study of Black American life and current scholarly opinion is in favour of calling Du Bois the Father of American sociology. One does not fail to recall that Ambedkar too did the first detailed study of Shudra life and living conditions in the modernist sense, depicting their plight, substantiating that with facts and arguing for their rights) clearly indicated his role as a vanguard, who would take up the issue of Black reconstruction in America in days to come. His crusading zeal for the upliftment of the Blacks was immediately recognized with the publication in 1903 of The Souls of Black Folk and he was invited to be the director of the research wing of NAACP and started to publish the Crisis magazine which will subsequently become the torch bearer of Black culture and Black struggle in America.

Most of the Harlem Renaissance writers including Langston Hughes were first published in the Crisis magazine through the direct intervention and initiative of Du Bois. Ambedkar, too, struggled to get a decent house in upper caste localities in India and had to negotiate with Indian caste system to get a decent job even after his return from abroad and was instrumental, like Du Bois in America, for ensuring various legislative rights for the Dalits and other oppressed classes in our society. Like Du Bois, Ambedkar also instituted political organizations for the Dalits and initiated publications such as Bahiskrit Bharat (1927) and Mook Nayak (1920) for the articulation of underrepresented voices of the outcast. As Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk has been hailed as the ‘political Bible of the Negro race’ (Edwards, 2007, VII), Ambedkar’s Annihilation of Caste is the first modern polemical treatise to capture the vices of caste and the traumas of the Dalits. So far no comprehensive comparative study of Du Bois and Ambedkar has been attempted although they share so many commonalities in their vision of a just world.

2018 happened to be the 150th birth anniversary of Du Bois and scholars are revisiting his works and ideas to evaluate present day resistance movements like Black Lives Matter, Demand for Reparation etc. In a similar vein, we are witnessing now an “Ambedkar renaissance” that should motivate us to undertake new intersectional studies on caste and race, or “interraciality”, prompting us to read the two thinkers together for better insight on modalities of contemporary resistance struggles. There are greater scopes to make comparative studies on their mutual views on democracy and religion. My forthcoming work makes a strong case for a joint study of Du Bois’s The Negro Church (1903); “Of Our Spiritual Strivings” and “Sorrow Songs” (2007) and Ambedkar’s The Buddha and his Dhamma. Their constitutionalism, their thoughts on radical resistance, their political philosophy and organizational principles, if studied together may yield a composite vision of democratic universalism, so highly in need today.

Both W. E. B. Du Bois and B. R Ambedkar viewed liberal humanities education as immensely empowering for the universally dispossessed such as the Blacks and the Dalits. Du Bois’s debate with Booker T. Washington on the necessity of liberal arts education for the upliftment of the Blacks led to his scathing critique of Washington for his “Atlanta Compromise”, a treaty in which Washington bargained for minimum facilities for the African Americans in exchange of their acceptance of second category citizenship. Du Bois vehemently opposed such compromise and demanded full and equal rights for Blacks, a fight that reminds us of Ambedkar’s fierce opposition to Gandhi for the latter’s accommodationist approach to the caste question. Du Bois’s resistance to the Atlanta Compromise and Ambedkar’s initial opposition to the Poona Pact are historic events which altered the vectors of Dalit-Black emancipation struggles.

Dalits and Blacks continue to be in the margin of the higher education fold even today and that reinforces the need to revisit these histories of continental struggles to gain new epistemes for justice. Borrowing Achilles Mbembe’s argument in his Critique of Black Reason that the term ‘Black’ refers to an universal condition of stigmatization, legitimized by a codified logic of dispossession and depredation, I would argue that such systemic transnational networks of discrimination or ‘Black Reason’ are generating today new norms of disenfranchised precarities that virtually enforces a “Becoming Black/[Dalit/Minor] of the world”. Given that, we may recall Du Bois’s idea of Black Internationalism and cosmopolitanism that connected him to Ambedkar who was fighting for the emancipation of the Dalits way back in the 1940s in India. This paper therefore, argues for a critique of Dalit/Black/Minority reason that universalizes the question of discrimination across different registers of persecution.

As the Blacks, the Dalits and other multiple numbers of oppressed groups are being persecuted on almost every day basis today, how do we re-read the crusading mission of both Du Bois and Ambedkar in the contemporary context? How do we re-engage today Ambedkar’s debate with Gandhi on the question of caste and social reform? How do we execute Ambedkar’s slogan - “Educate, Agitate and Organize” and Du Bois’s dream of materializing the upliftment of the “Talented Tenth [Negros]” (Edwards XIX) and the “strivings of the Negro People” (Edwards, 2007, XII)?The problem of the twentieth century, for Du Bois was the “problem of the colour line” and the problem of the twenty first century appears to be more complicated, it is the problem of precarity or minority or refugee-hood and neo-imperial ambitions. In other words, to quote Du Bois “the veil” (Du Bois’s words used in The Souls of Black Folk for segregation) today has got multi-layered and manifolded. The paradigm of Black/Dalit/minority/precariat reason prevails. In what follows I shall dwell on Achille Mbembe’s idea of “critique of Black Reason” which reinforces Du Bois’s original argument for global dimension of discrimination and ‘making common cause’ with fellow sufferers.

Globalectics and Critique of Black/Dalit Reason

In spelling out this conjunctive reading I engage with some theoretic coordinates and I elucidate them first to clarify how they have enabled me to map a schema of conjunctive reading. Reiland Rabaka in his book W. E. B. Du Bois and the Problems of the Twenty First Century has drawn on Du Bois’s radical ideas to reflect on contemporary issues of racial and other forms of segregation. He also did connect Du Bois with postcolonial strivings in his chapter in this book titled, “Du Bois and the Politics and Problematics of Postcolonialism” but his study is primarily and exclusively confined to “Africana critical theory” which though necessary, does however, lack that global outreach which Du Bois- envisioned. I would therefore engage with two more recent works and my arguments would rest on the findings of these works to constitute a new critical theory of Afro-Dalit-Minority reason. The two thinkers whose works I have in mind are Achilles Mbembe and Ngugi Wa Thiongo. Mbembe’s idea of Critique of Black Reason and Ngugi’s idea of the ‘globalectics’ are crucial to foreground the emerging logic of “interraciality” and here I quote from the introduction to their recent work in this field by Bacchetta, Mairna and Winant in their Global Raciality: Empire, PostColoniality, DeColoniality--

… The writers included in this book engage with these questions, exploring how racialized identities and experiences are produced across different registers in a global context. Several chapters offer a transnational approach to raciality that is both sensitive to local specificities and explores how notions of race travel across national borders. For example, Padma Maitland’s chapter on Dalit communities in India highlights the connections that Dalits themselves have established between their own struggles and African-American conditions and resistance. No one who took part in the United Nations World Conference against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance, held in Durban, South Africa in 2001, could have missed these links, due to the massive participation of Dalit people at the event. (Bacchetta, et al. 5)

I explicate first these ideas to show how critical ideas offered by Mbembe, Ngugi and the three authors just quoted underscore the continuation of the racial legacy and other forms of segregation across the globe and how such discriminatory logics are aided by global capital and the right wing surge for “Homonationalism” (Bacchetta, et al. 4). In other words, I am hinting at executing Du Bois’s radical ideas to resist present day laissez faireinduced fascistic social division across the globe. For Mbembe, the Kantian critique of pure reason has failed to bring justice to the world because there has been no critique of the Black reason and here the category of the ‘Black’ has been used by him as an expansive signifier that connotes not just skin colour but the colonizing tendencies which are inherent in contemporary institutional and economic practices. So a critique of Black reason suggests a critique of discrimination, and critique of colonial reason that continues to hegemonize our socio-political fabric. Recent incidents of racial attack in Charlottesville, the Black Lives Matter Movement, the Palestinian Struggle, the struggle of the Dalits or the lower castes in India, the fight for minorities, the immigrants – all point to the continued colonisation of the life world. Given all these pervasive forms of domination and segregation in the present day world, how do we revisit Du Bois’s theory of Pan-Africanism and Ambedkar’s call for democratic social endosmosis? How do we reframe the idea of Souls of the World Precariats whose sufferings symbolise the Black/Dalit/Colonized/Minoritized reason? For that we have to re-read Du Bois and Ambedkar through the theoretical frames of Mbembe and Ngugi and global raciality. As Mbembe points out--

Reason in particular confers on the human a generic identity, a universal essence, from which flows a collection of rights and values. It unites all humans... The question... was whether blacks were human beings like all others’ (85)

The answer for many Whites was - No. This holds equally true for Dalits and minorities and Mbembe further argues how Kant’s second formulation of the categorical imperative that exhorts us to treat humanity not as a means but as an end is also not applicable to the black people. This exactly matches with the Brahminical world view about the Shudras or the ‘untouchables’. Since the beginning of the eighteenth century, according to Mbembe, Blackness and race have constituted the (unacknowledged and often denied) foundation, from which the modern project of knowledge— and of governance— has been deployed(Mbembe4). If we just replace the word ‘black’ here with the word ‘untouchable’ then we get Manu’s vicious project of legitimizing Varnashrama or caste hierarchies. By reducing the body and the living being to matters of appearance, birth (the Dalit according to the Indian caste system is the lowest born and therefore ‘untouchable’), skin, and colour, by granting skin and colour the status of fiction based on biology, the Euro- American world has made Blackness and race two sides of a single coin, two sides of a codified madness(Mbembe 6). One immediately remembers the ‘Madness of Manu’ (Rege) in this context as what colonial modernity stands for Du Bois and Mbembe, Brahminism stands for Ambedkar. If race is the unreason produced by colonial Euro-modern logic, caste is the unreason constituted by the social logic of Brahminism. For the first time in human history, according to Mbembe, the term “Black” has been generalized. This new fungibility, this solubility, institutionalized as a new norm of existence and expanded to the entire planet, is what he calls, the “Becoming Black of the world” (Mbembe 6). One may argue that we can disperse the category of the Black to other signifiers such as the colonised and the Dalit or the lowest of the castes as they and their bodies too have been subjected to merchandise, chaining, controlling and subjugation. If we accept this idea of the dispersal and the dissonance of the category of the Black then Pan-Africanism cannot be confined to Africa or to a particular continent, it is deterritorialized for a greater revolutionary cause that has universal application and provenance. Critique of Black Reason therefore simultaneously stands for critique of Dalit and Precariat reason. Du Bois and Ambedkar emerge through this optic, Pan-global thinkers whose radicality has planetary repercussion for all times to come.

Coloured Cosmopolitanism/Pan-Africanism: Phenomenology of Being Black/Dalit

Du Bois’s commitment for the Pan-African ethics to unite all the disenfranchised sections of the world together and the Bandung anti-colonialism conference of 1957 (an event to which Du Bois was banned to attend by the US government for fear of global impacts through his words) are to be seen in the light of this Pan-African desire to enfold all the Asian and African brethren who shared a common history of dislocation, disruption and disenfranchisement. A collective phenomenology of dispossession and humiliation was recognized by Du Bois and Ambedkar throughout their lives and works.

Postcolonial scholars have theorised on how to provincialize Europe and how to decolonize but in forging decolonial theories, Du Bois and Ambedkar can be engaged in a more significant way. There are existing works on a comparative analysis of caste and race, and a memo available in the Columbia University Ambedkar archive mentions that Ambedkar himself was aware of Herbert Apthekar who was very close to Du Bois and who was also a member of the American Communist Association. The fact that Ambedkar knew of Apthekar as evident from his quoting him at length in his What Congress and Gandhi Have Done to the Untouchables suggests that Ambedkar was well aware about civil rights movements and democratic mobilisations in the USA on the question of Jim Crow laws and therefore there might have been an easy correlation between the Ambedkar, Du Bois and their struggles. All these conjectures point to a rich history of coloured solidarity or ‘coloured cosmopolitanism’ which was necessitated because of the intersectional or related nature of the various problems of segregation. Ambedkar has previously been studied with Gramsci (Cosimo Zene) and with many other philosophers (Choudhury) and this augurs well for future configurations of Dalit studies and postcolonial theoretic dialogue with the West. We can attempt similar epistemic or dissensual conjunction that would have futural ramification. Nico Slate’s Colored Cosmopolitanism: The Shared Struggle for Freedom in the United States and India provides a detailed chronology of these long association between leaders of colonized and caste ridden India and Jim Crow America. Slate talks about transnational solidarity among colored people to abolish segregation on color. Slate argues about similarities between white supremacy and Brahminical superiority under the caste system, also drawing similarities between American and British colonialism. He mentions Jotirao Phule, anti-caste crusader and author of Gulamgiri who wrote about a clear parallelism between caste and slavery. Slate also refers to Amanda Smith, the Christian evangelist who was herself a slave and who went to India to converse with Indian leaders and to serve the Indian downtrodden. Slate’s study clearly testifies the long link between India and African Americans.

We also come across in Slate’s book the reference to one black leader who mentioned Rammohan Roy while opposing racism in the US Congress referring to Roy as the great leader of Hindu monotheism who opposed all forms of hierarchies in Indian society. Even Gandhi also, we are told, wrote an essay on Booker T Washington and Gandhi’s settlement ashrama in South Africa was modelled on the Tuskegee Institute set up by Booker T Washington for Black emancipation. Du Bois knew about Asia and African problems when he was in Fisk University and when he went to Berlin for higher studies he came to know more about the Asian problem and realised that slavery is to be jointly viewed and resisted as global problem for the coloured races. All these associational histories may prompt us to undertake a comparative reading of Annihilation of Caste and The Souls of Black Folk– a reading that can throw up new insights to make common cause with persecuted beings across the globe, helping in the process to constitute a more workable phenomenology of being Black/Dalit or a minority/stranger. This is, therefore, a project on planetarity thinking or thinking in postcolonial internationalism, involving Ambedkar and Du Bois.

Conjunctive Milestones: Annihilation of Caste & The Souls of Black Folk as Manifestos for Change

The Souls of Black Folk and Annihilation of Caste are different in temporal and geographic location, one published in 1903, the other in 1935. They are also different in scope, manner of articulation, range of vision, and technique and volume of substance but reading these two seminal texts together provides a wealth of thought in planetary thinking. Annihilation of Caste was designed as a speech that was never delivered, The Souls of Black Folk was, however, in the form of different essays assembled as a book, it is largely lyrical and subjective, narratorial, biographical and anecdotal, fictionalised, different genres merged in one, even musical notes are there too. Annihilation of Caste, on the other hand is more polemical, impersonal and hard hitting. Annihilation of Caste is more in the form of direct argument and is a complex and well thought out documentation of Indian social systems and the Hindu Order of Life. The Souls of Black Folk is one of the most poignant articulation of Negro plight, their historical dislocation, persecution under slavery and perpetual denigration for being Black. The book begins with that perennial question, “How does it feel to be a problem?” (7), the Negro was made to feel by White supremacists that they are a problem as Shudras are stigmatized to appear as a problem in their own eyes. Du Bois went on posing similar questions in the book for all of us to answer such as “Why did God make me an outcast and a stranger in mine own house?” A perceptive reader immediately remembers Ambedkar recounting, right at the beginning of Annihilation of Caste how

Ramdas, a Brahmin saint from Maharashtra, who is alleged to have inspired Shivaji to establish a Hindu Raj… Ramdas asks, addressing the Hindus, can we accept an antyaja [last-born, untouchable] to be our guru because he is a pandit (i.e., learned)? He gives an answer in the negative… What replies to give to these questions is a matter which I must leave to the Mandal [the organisation who invited Ambedkar to deliver his talk on Annihilation of caste but who later asked him under pressure from upper caste Hindu society to modify Ambedkar’s scathing critique of Hindu theological texts]. The Mandal knows best the reasons which led it to travel to Bombay to select an antyaja – an Untouchable – to address an audience of the savarnas [upper caste]… I know that the Hindus are sick of me… (Ambedkar 209)

Pitted against these caste-ridden atrocities, was the democratic and constitutional desires of Ambedkar to bring forth social justice and egalitarian claims of all sections of society. In Ambedkar’s analysis caste is the biggest impediment in India’s march towards democracy and social endosmosis. Ambedkar talked of slavery, lack of public spirit and the impossibility of social revolution in India because of the caste system. He even compared it with slavery. In similar fashion, Du Bois captures the same history of bigotry and injustice in America for the Blacks in The Souls of Black Folk

The history of the American Negro is the history of this strife, - this longing to attain self-conscious manhood … he would not Africanize America … he would not bleach his Negro soul in a flood of white Americanism, for he knows that Negro blood has a message for the world. He simply wishes to make it possible for a man to be both a Negro and an American, without being cursed and spit upon by his fellows, without having the doors of Opportunity closed roughly in his face. This, then, is the end of his striving: to be a co-worker … (Du Bois 9)

So the problem of the twentieth century for Du Bois was the “problem of the color-line – the relation of the darker to the lighter races of men in Asia and Africa, in America and in the islands of the sea” (The Souls of Black Folk xv) and the plight of slavery for the Negros continues and every page of The Souls of Black Folk registers this pain

Lo! We are diseased and dying, cried the dark hosts; we cannot write, our voting is vain; what need of education, since we must always cook and serve? And the Nation echoed and enforced this self-criticism, saying: be content to be servants, and nothing more; what need of higher education for half-men? (Du Bois 13)

This anguish over the status of “half-men” is akin to the lower status of the Dalits. Caste, Ambedkar observes in Annihilation of Caste, is not a racial division but “it is a social division of the people of the same race” (238). Hence for Ambedkar, the idea of Hindu society is a myth, it was never one but segregated within and it does not have any sense of fraternity. Hindu society does not exist, it is only a collection of castes, and caste therefore is an objection to liberty and is a kind of slavery system. (Ambedkar, Annihilation of Caste260). “Of the Black Belt”, the sixth chapter of The Souls of Black Folk contains the most poignant articulation Black suffering and it goes to the credit of Du Bois for rendering this effectively in the book--

… “I have seen niggers drop dead in the furrows, but they were kicked aside, and the plough never stopped. And down in the guard house, there’s where the blood ran”… With such foundations a kingdom must in time sway and fall (86).

The ‘Black Belt’ was the American South known for its horrendous slavery system and musing through this chapter brings us to Ambedkar’s rendition in Annihilation of Caste of the battles and regular humiliation of different untouchable castes in India. Ambedkar, we may recall, also refers to the rude system of penology enforced by the Hindu social order to maintain caste, he refers to Shambuka’s murder by Lord Rama for violating the caste order. If the Black Belt was confined within the American South, the Dalit Belt in India spans across the board. The third chapter of The Souls of Black Folk on “Of Mr. Booker T. Washington and Others” posits Du Bois’s argument for equal status for Blacks and his entire ground of debate with Mr. Washington who as a Black leader adopted a compromising stance. The new Critical edition of Annihilation of Caste (2014) with a critical introduction by Arundhati Roy contains Ambedkar’s debate with Gandhi on similar grounds. In spite of wide divergences in terms of contextual and historic differences, it is really enlightening to see to two towering thinkers debating with established leaders in their own constituencies on similar and legitimate grounds. Ambedkar referred to John Dewey and other American thinkers of democracy in his rebuttal to the claims of caste system. Du Bois and Ambedkar both had training in social anthropological analysis and on economic issues, and both analysed the root cause of racial segregation and caste related stratification through a study of social structure and the political economy of exploitation. Ambedkar ends Annihilation of Caste in this prophetic tone—

More important than the question of defending swaraj is the question of defending the Hindus under the swaraj. It is only when Hindu society becomes a casteless that it can hope to have strength enough to defend itself. Without such internal strength, swaraj for Hindus may turn out to be only a step towards slavery (317).

Du Bois ends Souls of Black Folk in an identical breath, emphasizing Black self-respect and right and hope for freedom -

Our song, our toil, our cheer, and warning have been given to this nation in blood-brotherhood … would America have been America without her Negro people? … anon in good time America shall the Veil and the prisoned shall go free. Free, free as the sunshine trickling down the morning … (176)

There cannot be a better way to end, and both these two thinkers have reiterated the contribution of each and everyone of our great human family and we go back to the lines of Walt Whitman which I used in the earlier section of this essay from a newspaper report that used Whitman’s words on the equal importance of every member of the human family in the “eternal purport of the Earth”. Du Bois’s brilliant expression of the idea of “blood-brotherhood” constitutes the leitmotif of all strivings for freedom. The project of Annihilation of Caste and the rendition of The Souls of Black Folk is to drive home Du Bois’s vision of the “mighty rainbow of humanity”, the blood-brotherhood of all.

Conclusion

Andrea M. Slater in her essay “W.E.B. Du Bois’ Transnationalism: Building a Collective Identity among the American Negro and the Asian Indian” has shown how Du Bois wanted to forge a coalition between African Coloured people and Asians and wanted to see how the “habit of democracy must be made to encircle the earth”, and this is more clearly evident in W.E.B. Du Bois’s famous address, “To the World” (Manifesto of the Second Pan-African Congress) published in Crisis magazine, November 19, 1921. This desire for democracy encircling the earth aligns Du Bois with Ambedkar as the latter, too, was an untiring advocate of the democratic spirit. The problem of the colour line or caste line has not been erased today but in the words of Shawn Leigh Alexander, who wrote the new introduction to the 2018 new critical edition of The Souls of Black Folk, “Activists, scholars, and individuals … will continue to look to fugitive pieces assembled between the book’s cover [The Souls of Black Folk & Annihilation of Caste] for some guidance because, unfortunately, too many of the questions and answers Du Bois [and Ambedkar] was contemplating … are all too analogous to those many are examining today.” (xxi). So the history of Afro-Dalit assemblage continues.

Acknowledgement: The author acknowledges his deep gratefulness to USIEF, and US Fulbright Commission for the Fulbright Nehru research fellowship that made this work possible through archival visit to the Du Bois Archive in University of Massachusetts, Amherst in 2018. Special thanks to Dr. Robert Cox and to all the other archival staff at the Du Bois Archive and also to the Director and staff in the Du Bois Centre, and the W. E. B. Du Bois Library, University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Works Cited

Alston, V.R. “Cosmopolitan Fantasies, Aesthetics, and Bodily Value: W. E. B. Du Bois’s Dark Princess and the Trans/Gendering of Kautilya.” UC Santa Barbara Journal of Transnational American Studies, vol. 3 no. 1, 2011. Web.

Ambedkar, B. R., Annihilation of Caste, New critical edition with an introduction by Arundhati Roy. New Delhi:Navayana, 2014. Print.

----------------- Writings and Speeches, Vol. 10, Ed. Vasant Moon, Government of Maharashtra: 1991, Reprinted by Ambedkar Foundation: 2014. Print.

Bacchetta, Paola, Maira, Sunaina; Winant, Howard, Global Raciality: Empire, PostColoniality, DeColoniality. New Yyork: Routledge. 2019. Print

Bhabha, Homi K. “Global Minoritarian Culture.” Shades of the Planet: American Literature as World Literature, Ed. Wai Chee Dimock and Lawrence Buell, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. 2007. pp. 184-195. Print.

Du Bois, W.E.B, Darkwaters: Voices from Within the Veil. New York: Harcourt, Brace and How, 1920. Print.

----------The Souls of Black Folk, Ed. with an introduction by B H Edwards, New York: Oxford University Press, 2007. Print.

---------- The Souls of Black Folk, Essays and Sketches, with introduction by S L Alexander, Amherst and Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2018. Print.

Du Bois Archive, University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Goyal, Yogita, “On Transnational Analogy: Thinking Race and Caste with W. E. B. Du Bois and Rabindranath Tagore”, Atlantic Studies, 16:1, 2019: 54-71. Print

Mbembe, Achille, Critique of Black Reason, Trans. Laurent Du Bois, New York: Duke University Press. 2017. Print.

Parker, Percy L. Public Opinion, 21 July, 2011. Front Page. Print.

Prashad, Vijay. “Afro-Dalits of the Earth, Unite!”African Studies Review, vol. 43, No. 1. 2000. 189-201. Print.

Rege, Sharmila, Against the Madness of Manu: B.R Ambedkar’s Writings on Brahmanical Patriarchy, New Delhi:Navayana. 2013. Print.

Slater Andrea M. “W.E.B. Du Bois’s Transnationalism: Building a Collective Identity among the American Negro and the Asian Indian”, Phylon, vol. 51, no. 1, Fall 2014: 145-157. Print.

Thiong’o Ngugi wa, Globalectics: Theory and the Politics of Knowing. New York: Columbia University Press. 2014. Print.

Visvanathan, Shiv. “The Race for Caste Prolegomena to the Durban Conference,” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 36. no. 27, July 7, 2001. 2512-2516. Print.

Zelliot, Eleanor, Ambedkar Abroad: Sixth Dr. Ambedkar Memorial Annual Lecture, New Delhi: Jawaharlal Nehru University Publication. 2004. Print.

Anindya Sekhar Purakayastha

Professor

Kazi Nazrul University, India

anindya.purakayastha@knu.ac.in

©Anindya Sekhar Purakayastha 2019