Ghosts, Drunkards and Bad Language: Translating the Margins of Nabarun Bhattacharya's Kāṅāl Mālsāṭ (‘The War Cry of the Beggars’)

Carola Erika Lorea

Introduction

The President of the United States Donald Trump deserves to be recognized for the invaluable merit of having reminded the world how problematic it is to translate slang terms. In January 2018, Trump inadvertently contributed interesting material to international linguistic disquisitions when he had the unfortunate idea of defining some African countries as “shitholes.” The translation of such colorful vernacular expression on the headlines of international newspapers became a topic of conversation: journalists reflected on the fact that in other languages on the global media the shithole remark “does not quite translate” (Walters). Taiwan's central news agency decided to translate it as, literally, “countries where birds lay no eggs”; in the French Le Monde a more explicit “pays de merde” was used; in Italy the scatological connotation was maintained by choosing terms like “cesso di paese” (latrine countries). In any case, polyglot journalists realized that something was missing in the translation of the President’s outrageously disrespectful remark. I couldn't but share the general feeling of dissatisfaction and incompleteness with the translation of politically charged swearwords.

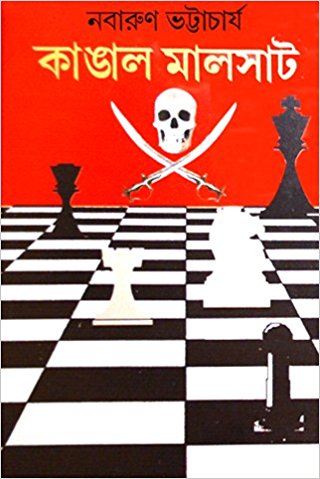

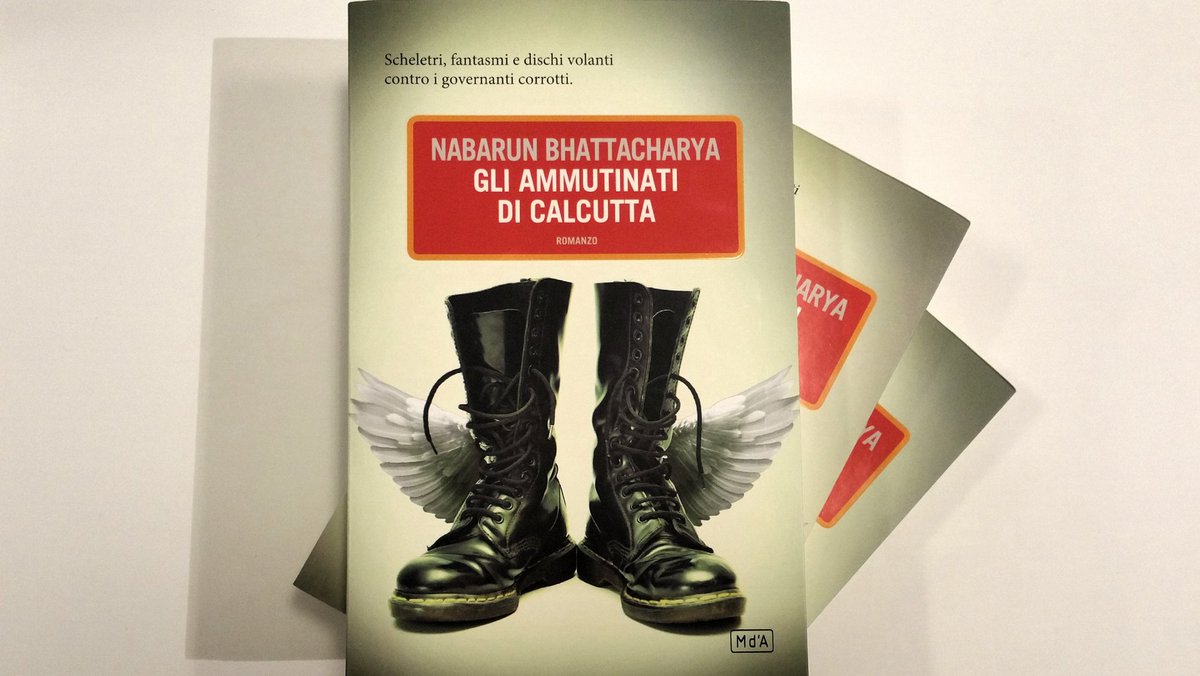

This article is an occasion to share some problematic aspects encountered in this domain. It concerns what I consider one of the most challenging translations of my life, both as a scholar, who regularly translates literary material for academic purposes, and as a literary translator. In 2016 the Italian publishing house Metropoli d'Asia released my translation of Nabarun Bhattacharya's Kāṅāl Mālsāṭ,[1] conventionally translated as “The War Cry of the Beggars”, with the Italian title Gli ammutinati di Calcutta (Calcutta's Mutineers).[2] The title might already reveal some of the issues that resulted from a clash of priorities between the publisher and the translator. In fact, in the contract that I was offered, I had to sign that I would agree with every change that the editors apply to the submitted translation – including the title. The version that came out after the revision of the publisher’s editorial team was in many ways different from my first draft. The title had been changed from “Miserabili all'attacco” (Miserables, attack!) into “Gli ammutinati di Calcutta” (Calcutta’s Mutineers); significant passages of the text had been cut (some of them, after strenuous negotiations, were able to be re-integrated); and several neologisms and regionalisms which I had used in order to translate Nabarun's eclectic and often non-standard language had been changed into more standard Italian words. The final revision thus reflects a mainstream commercial concern for domestication[3] (Venuti) and for the acceptability principle (Toury), a process that has been associated with cultural imperialism – especially when the translation in question is from postcolonial literature to a European readership. The editorial choice, in this sense, stands in sharp opposition to Nabarun Bhattacharya’s intellectual intentions, and fails to reflect the principle of subaltern resistance which the novel incarnates both in its plot and its language. The publisher's changes are equally reflected in the choice of the book cover. The original cover (see Figure 1) displays a skull and crossed swords on a red background, in the center, floating on the top of a chessboard. The latter reminds one of the famous Satranj Ke Khilari (The Chess Players (1977), dir. Satyajit Ray), a historical as much as surreal movie that criticizes the last Mughal rulers. The cover of GADC (see figure 2) portrays simply a used pair of military boots bearing a couple of wings on their side, à la Hermes. At the top of the Italian book cover a catchy explanatory couplet was inserted: “Scheletri, fantasmi e dischi volanti / contro i governanti corrotti” (“Skeletons, ghosts and flying saucers against the corrupt rulers”). At the first glance, KM’s appearance strikes one by its simplicity and subversiveness: it evokes a larger political game in which clumsy pirate-like characters are passionately engaged. Its outlook would suggest that the book is a guerrilla manual for improvised semi-magical soldiers. The cover of GADC, on the other hand, takes itself much more seriously: the image that the publishers sought to transmit is that of a truthful rebellion against unjust powers. The publisher’s linguistic editing of my translation of KM similarly reflects a conscious attempt to tame the extravagant picaresqueness of Nabarun’s style and reduce it to a more realistic, consumable and standardized language of political dissent. This might have rendered the Italian version of KM more attractive on the market, but the result was (in the hyper-sensitive opinion of its translator) a slightly washed-out version, in which much of the original work’s complexity has faded away.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 2.

Aspects of the 'translation impossible' elucidated in this paper aim to disentangle and justify the numerous nuances that had to be 'left out' of the target text, because of social and cultural differences that failed to make it through the equivalence-seeking mechanism of literary translation. I focus my attention on the translation of slang, and particularly on alcohol-related slang and on registers drawn from the margins, employed to discuss socially delicate themes. I argue that these instances of translingual failure, which have a great deal to tell us about cultural difference, social values and taboos, are locations where the politics of radical translation can emerge, and where a subtle balance between faithfulness, creativity and “horizons of expectations” needs to be struck within our translation practices. Thinkers in the tradition of reception aesthetics[4] have theorized readers’ responses as the product of affective, contextual and subjective factors, including the “horizon of expectations” that the public projects on the content, meaning, and aesthetics of the text (Jauss). By pluralizing the expression, I suggest we also include here (in the specific context of translation) the multiple expectations that a translator projects onto the implied readers of the text which is being translated. For a working definition of slang, I follow Connie Eble's idea that “slang is an ever changing set of colloquial words and phrases that speakers use to establish or reinforce social identity or cohesiveness within a group or with a trend or fashion in society at large” (Eble 11). Jonathon Green, in the introduction to his massive dictionary of English slang, defines it most beautifully: "Slang is the language that says no. Born in the street it resists the niceties of the respectable. […] It is a subset of language that since its earliest appearance has been linked to the lower depths, the criminal, the marginal, the unwanted or even persecuted members of society. [...] Its dictionaries offer an oral history of marginality and rebellion, of dispossession and frustration. [...] I would call slang a counter-language: the desire of human beings, when faced by a standard version [...] to come up with something different, perhaps parallel, perhaps oppositional" (Green 5-6, my italics).

In the following sections, attention is drawn to Nabarun Bhattacharya’s use of slang and underground colloquialisms: a counter-language that poses a veritable challenge for the translator. Suggesting that a radical literary text, such as KM, needs a radical translation, and ultimately a radical reader, I resist the idea of the “invisibility of the translator” that is prominent in the mainstream publishing industry (Venuti, 1-2) and I affirm the necessity of marking the novel’s foreignness. I will provide examples of how a radical translation can reflect in its form, style and language the radical source novel, for instance by integrating from a linguistic point of view the non-standard and the marginal, regionalisms and jargons, making the target language unsettling and unfamiliar. The choice of privileging “foreignization and resistance” (Myskia) has been systematically undermined by the publisher’s editing policies, which aim at normalization, fluency and readability. Nevertheless, appealing to the ethics of the implied readers as radical – intended as 'going to the roots' of the performance of literary communication with curiosity and readiness to discard standard commercial literary assumptions – I suggest that the translated text is still capable of communicating the social issues portrayed in the original novel. Delivering the translated text from the shackles of translation seen narrowly as efficient communication from the source to the target, I include the responsibility of the readers’ reading practices (Zhou; Mossop) as a fundamental part of the transcultural circulation and attribution of meaning.

Nabarun Bhattacharya and the Language of the Margins

In this section I provide a short informative background on the author and his work. Nabarun Bhattacharya (1948 – 2014) was a Bengali novelist, a maverick poet and a writer of short stories. His irreverent and innovative style has been variously defined as magic realism[5] (P. Basu; Haque), critical irrealism (S. Bhattacharya), literary Bolshevism (Purakayastha) and anarchic surrealism (Lorea), suggesting the author's capacity to criticize contemporary neoliberalist politics and denounce unequal societies with the weapons of the bizarre, the spectral and the trivial. Explicitly inspired by the Russian anti-establishment writer Mikhail Bulgakov (1891 - 1940), Nabarun absorbed political ideals, literary influences and a strong emphasis on activism from his father, Bijan Bhattacharya (1915 - 1978), the leftist playwright who authored Nabānna in 1944, and his mother Mahasweta Devi (1926 - 2016), a famous literary voice of Indian feminism and tribal resistance. The small but growing corpus of literary criticism surrounding Nabarun's work seems to pinpoint two fundamental aspects of his oeuvre: the centrality of “the margins” of postcolonial urbanity (S. Bhattacharya; Hříbek) and the use of uncensored 'low' language. The former points to the setting as well as the characters of Nabarun's work, inseparable from underground Kolkata, and populated by subaltern anti-heroes: unemployed drunkards with flying superpowers,[6] fuel-drinking prostitutes,[7] vagabond dogs (Bhattacharya, Lubdhak), black magicians and petty criminals.[8] The latter concerns Nabarun's exceptional use of a hectic Bengali prose that can swing from highly literary and erudite registers to the bottom-most informality of filthy slang, obscene words, subversive jargon and abusive insults, highlighting “a unique locus of artistic activism that abhors all forms of aesthetic compromise in the name of decorum and aestheticism” (Purakayastha). The two aspects are closely related: Nabarun's language speaks the tongue of Kolkata's margins and reflects his ideas on the abyssal gap between a lethargic bourgeoisie spoiled by consumerism, and the exploitation of oppressed subaltern classes. The literary contribution of Nabarun Bhattacharya was given official recognition when his novel Hārbārṭ (1993) received the prestigious Sahitya Academy Award. However, his overt advocacy of revolutionary violence and his sympathy towards the Maoist movement resulted in a controversial reception of his work in the state of West Bengal, whose authorities have often looked at Nabarun's satirical voice as dangerously suspicious.[9] Although he has never formally adhered to any political party, Nabarun's fearless pen is obviously affiliated to the radical left, “but no further left than the heart”, as he loved to say during interviews (Bag). The (socio)linguistic aspects on which I focus my attention in this paper are drawn from the novel Kāṅāl Mālsāṭ (2003), which has not been translated into any other language apart from Italian, as yet.[10] In the following sections I will unfold some problematic aspects of translating Nabarun’s ‘language of the margins.’ Here I intend marginal spaces as social, ontological and linguistic. The low and informal registers of Nabarun’s characters emerge from socially marginalized milieus, but also, and simultaneously, from the margins between life, death and afterlife: nebulous border spaces populated by ambiguous characters, who cross the boundaries between the real and the imaginative, the truthful and the magical, political subjectivity and the supernatural revolutionary.

Kāṅāl Mālsāṭ’s Ghostly Creatures: Translating Invisibility

Kāṅāl Mālsāṭ is the story of the coalescence between two groups of fantastic beings, the Fyatarus and Choktars, both outsiders with respect to the models and expectations imposed by the hegemony. Through their partnership and solidarity, they enact a tragicomic and carnivalesque guerrilla against the ruling classes. The mutiny which constitutes the core of KM is strategically achieved through the mass mobilization of ghosts, flying saucers, drunkards, mendicants, and various antisocial elements inhabiting the dark and forbidden alleys, whorehouses, morgues, police stations, footpaths and slums of Kolkata.

The alliance between these non-hegemonic spheres is clear from the very first pages of Nabarun's book. The macabre participation of dead people in the plot is signaled by the use of the candrabindu (ँ), the graphic mark of vowel nasalization. It is said in Bengal that ghosts speak with a nasal voice. The conversations between some of the characters have ubiquitous nasalization marks, persuading the readers that the characters pertain to a magic and spectral realm.[11] Nabarun introduces the first of such conversations by explaining: “the sounds and the sentences that were coming out [of the telephone-like apparatus] were quite unnatural, quite nasal, a bit ghost-like” (Bhattacharya, KM 39). Thanks to this remark, the text offers to the foreign readership an occasion to engage with cultural difference and relieves the translator of the need to add an explanatory footnote. Given the lack of nasalization marks in Italian, a language that does not allow ghosts’ voices to explicitly appear through conventional graphic signs, I added numerous “n”s at the end of words, as a compromise between domesticating and foreignising: “è la terza volta che provo a chiamartinnn, pensavo ti fosse successo qualcosannn!” “Che vuoi che sia successonnn? Stavo al gabinettonnn.”[12] In a different context, the use of the candrabindu sign indicates that a person is dead: as in English “(late)”, preceding a deceased person's name. When the sign precedes a proper name it means that the person mentioned is no more, which is why in Bengali slang “candrabindu haoyā” (to become candrabindu) means to “croak”, to “kick the bucket.” This is the acceptation of the candrabindu symbol that Nabarun draws upon when he ridicules his readers for not having read attentively what happened in the initial pages: modern readers, he writes, are used to TV serials and need regular recapitulation of the preceding episodes, thinking that the introductory pages were all just preceded by a giant candrabindu (Bhattacharya, KM 28). Needless to say, these connotations, which have a hilarious effect in the source text, can hardly find an equivalent when transcreated into Italian. In my translation, I used the symbol of the cross, †, in the sentence “tutte le pagine precedenti sono inutili e morte [...] prima di tutto questo non c'era altro che una grande †” (Bhattacharya, GADC 47), meaning “all previous pages are useless and dead [...] before all this there was nothing but a big †.” This is an attempt at achieving a “dynamic equivalence”[13] between source and target text: not only is the cross representative of death and of the deceased in the symbolic/gestural repertoires of Italian readers,[14] but corresponding expressions also exist in Italian colloquialisms (e.g. “metterci una croce sopra”, to put a cross on top of something, means to end, to finish it, to get over it). Characters of the ghostly and spooky type are ubiquitous in Nabarun’s literary production, reflecting that love for the occult, the dark and macabre that is so obviously constitutive of the writer’s oeuvre. Herbert, the protagonist of Nabarun’s most well-known novel, a failed medium who pretends to talk with the dead and ultimately explodes with an uproarious detonation inside the crematory oven, is somehow paradigmatic of this inclination. These liminal characters allow the author to represent the ultimate subaltern: so socially invisible that they could well be ghosts; so restless and hungry for justice that they would rather remain subversively active even after death, instead of resting in peace. The language of KM gives voice to such invisibilities: the invisibility of the socially outcaste who did not enter the gateway of neo-liberal affluence; and the invisibility of their linguistic repertories, which have been traditionally excluded by the polished and conservative conventions of high literature (Banerjee).

Slang and the Semantics of Boozing

Nabarun Bhattacharya has often been accused of vulgarity for the desecrating inclusion of slang terms, argot and cryptolects into the realm of Bengali literature. The sophisticated tone of mainstream Bengali literature celebrates the lyrical prose of Rabindranath Tagore, who enjoys a quasi-divine status referred to in Nabarun's irreverent words as “the puja of the beard” (dāṛipūjo) (Bhattacharya, KM 103). By contrast, the anti-aesthetic lexicon of Nabarun underlines his belief that “nothing could be more vulgar than the continued endurance of poverty and other forms of social coercions” (Purakayastha 20-22).

The expression most commonly used in Bengali to denote the colloquial, idiomatic language spoken by the less educated and marginalized sections of the city dwellers is rak-bāj.[15] It is literally the idiom used for conversations on the royāk (coll. rak), a verandah-like space that, similar to the American English “stoop”, allows those who are idly sitting on it to gaze at the street, tease the passers-by, play cards, and chit-chat at their leisure (Basu 78). In the first pages of KM, three fundamental characters, the Fyatarus, or flying humans, are introduced in a scene in which they are sitting on the royāk by the edge of a cremation ground, 'talking shit' about a man whom they see filling up empty bottles of booze with Ganga water. For a Bengali reader, the setting of this scene provides an immediate point of reference for the cultural and social background of the characters. In the Bengali imagery, cremation grounds (śmaśān) are spooky places populated by ghosts, drunk Tantric sadhus, marginal and antisocial elements. From the perspective of the more powerful classes, the royāk is the typical setting for the 'time-pass' of unemployed urban males, boasters and braggers. Rak-bāji is perceived as the way of talking of uneducated and unsophisticated people, possibly involved in some illegal business or in small criminality, acting as neighborhood gangsters and devotedly dedicated to heavy drinking. When I translate the crematorium-royāk setting into Italian, there is no equivalent that I can use in order to transmit similar connotations. The Italian rendition of the royāk setting is simply “a ogni lato della banchina c'era una terrazza per sedersi” (Bhattacharya, GADC 30): on both sides of the ghāṭ, there was a platform to sit on. The reader of the Italian text is left in charge of slowly associating, in the course of their reading, the connotations and all the implied information related to the characters that are instead immediately accessible to the Bengali reader. Radical postcolonial literature-in-translation requires an extra amount of work not only for the translator, but also for her readers. It is my horizon of expectations with respect to the novel's readers that dictates such translation choices. If readers decide to approach a literary work in Italian embedded in the urban, social and political landscape of Kolkata, I expect them, as a translator, to be willing to put this extra amount of intellectual sensitivity and empathy into the reception process. These projected expectations concerning my readers’ willingness to deal proactively with the unfamiliar and the foreign have decisively influenced my selection of translation practice. Rehabilitating the infamous slang of the rak-dwellers, Nabarun suggests that rak-talk is not only an expression of the subaltern's language, of social discontent and transgression. It is also a space for creativity, a constructive, informal leisure that can lead to great ideas, such as planning mass mobilization – as in the case of KM’s characters – or extemporaneously composing hilarious satirical verses (viz. the poet-Fyataru Purandar Bhat, whose impromptu verses accompany the reader throughout KM).

Bringing this mode of discourse into the folds of Bengali literature is one of Nabarun's greatest contributions. At least since Samaresh Basu's novel Prajāpati (1967), the rak-bāj language has been used in direct dialogues between the Bengali characters of literary realism.[16] With Nabarun's novels (particularly Hārbārṭ and Kāṅāl Mālsāṭ), the use of slang finally shifted from the character's voice to include also the voice of the narration. Therefore, it should not be surprising that the prose of Nabarun Bhattacharya has been cited as the most authoritative source in the study of Bengali slang: the sociolinguistic and lexicographic research of Abhra Basu, based on both oral and written sources, quotes at length from Nabarun's writings. In his Dictionary of Bengali Slang (Bāṅlā Slyāṅ: Samīkṣā o Abhidhān) examples for slang usage are provided largely drawing from Nabarun's novels. This dictionary has been an important resource for my translation of slang and for my understanding of slang as a mode of discourse[17]– together with long, daily conversations and debates with the readers of Nabarun, my Bengali friends and colleagues living in and around Shantiniketan, where I worked on Nabarun's novel in 2014 and 2015. Among the various purposes behind the creation and usage of slang pointed out by linguists, I want to focus my attention on three in particular.[18] First, slang is cathartic: it is particularly prolific in the semantic fields of death and dramatic situations, such as sorrow, war and turmoil. It is used to downplay and take the edge off particularly serious and important subjects, such as death and sexuality. Second, slang is created to talk about social taboos: for instance, slang terminology is profusely used in the domains of sex, alcohol, and the consumption of drugs, not only to openly subvert conventional norms but also to secretly communicate about ostracized, illegal or socially reproachable matters. Third, for its suitability in expressing rage and resentment, cursing and abusing, breaking formality and subverting linguistic conventions and social conformism, slang is in itself anti-institutional and antinomian, and thus it constitutes a privileged linguistic resource to express dissent and transgression. In this light, Nabarun's language appears even more appropriate for the themes and tones that characterize his writing: a recurrent, almost obsessive, reflection on death;[19] a strong critique of the standards of hypocritical morality imposed by the dominant culture; and a tireless appeal to resistance. Kāṅāl Mālsāṭ's spirit can be summarized as the ungrammatical manifesto of an impossible revolution (Lorea 15). The author's denunciation of class inequalities and the abuse of power emerges clearly in the analysis of the use of the semantic field of alcohol drinking, a lexicographic reservoir from which Nabarun draws innumerable resources from various registers.[20] These social, cultural, political and ecological connotations related to the sphere of 'boozing' can hardly emerge in translation. As already mentioned, slang proliferates in line with social taboos. Drinking alcohol is a socially reprehensible activity in Bengal, it is completely banned in at least three Indian states (Bihar, Gujarat and Nagaland) and drinking is seen as blameworthy in several corners of South Asia.[21] This is obviously an over-simplified generalization: in order to understand the social dynamics and norms affecting drinking in India, we would need a more elaborate discussion to delve into the significance of class, caste, urban/rural divides, gender divides,[22] regulations and cultural differences varying from state to state, and other issues that we cannot extensively discuss here. Begging pardon for this generalization, I will limit the present discussion by pointing out that alcoholic drinks in West Bengal are, or better to say, have become, reprehensible goods of consumption. This has complex historical and political reasons, both endogenous and exogenous. The nineteenth century moral stain associated with the act of consuming alcohol entered the mores and the standards of decency of the urban educated elites (the so-called bhadralok society) and persists until today. Perhaps this is because, as remarked by Harald Fischer-Tiné and Jana Tschurenev, “when arguing that drink is alien to Indian culture, the middle-class social reformers who started to advocate temperance and prohibition from the mid nineteenth century onwards, confused their own elite values with Indian culture as a whole” (Fischer-Tiné and Tschurenev 5). Despite norms and social restrictions, alcohol consumption increased 55% in the last twenty years in India (Debroy). Pitted against such a paradoxical scenario, Nabarun’s prose and his virtuoso use of a rich slang related to booze in Bengali, emerge as powerful tools to ridicule, through an embroidery of colorful ‘bad’ words, the hypocrisy of governmental laws and the conformism of bourgeois bigotry. Unsurprisingly, in Bengali, ‘bad’ words associated with drinking and being drunk abound.[23] On the other hand, drinking in the Italian sociocultural landscape is not a transgression; on the contrary, moderate drinking is part of everyday life. Italians are socialized into a traditional wine-drinking culture from a young age, with their families and with peers, on diverse occasions. In Italian language the ‘bad’ vocabulary to define alcoholic drinks is very limited. There is no word in general to define alcoholic drinks in Italian slang which could be an equivalent to the Bengali māl or ‘booze.’ The only word associated with alcohol drinking that has a very negative connotation is the medicalized “alcolizzato”, an alcoholic. In my translation, to drink māl is often translated simply as “bere” (to drink), since in Italian “to drink something” already means, in informal registers, to drink alcohol. The effect is a softened equivalence, compared to the source language. Interestingly, a literal translation of māl as “roba” (both meaning 'stuff') in Italian can be used as a slang term for heavy drugs: ‘bad words’ and slang terms for drugs in Italian are abundant, a testimony of their status as illegal, socially reproachable and morally condemned substances. Colloquial ways of indicating alcoholic drinks exist in regionalisms and dialects (e.g. un'ombra – meaning a shadow – in Venice to refer to a glass of wine; tazzare – a verb deriving from the noun cup, tazza, used in Milan, meaning to go out for a drink) but they never imply negative, non-respectable or transgressive acceptations. Throughout my translation I attempt to maintain the foreignness of the source text, to “send the reader abroad” (Venuti 20) and to value linguistic and cultural differences by using realia (keeping 'untranslatable' words in their original language – for example, Bangla, bidi, sadhu), providing short explanatory paraphrases in the text, plus a final glossary and very few footnotes for historical facts and figures. On the other hand, I try in some cases to lighten the weight of the reader's engagement with the foreignness of the text. In one such case, I translated “kānṭri likar” (country liquor, referring to local toddy) as “grappa fatta in casa” (home-made grappa). Grappa is a traditional brandy-like distilled beverage obtained from the distillation of pressed grapes or other fruits. Some brands of grappa are produced industrially and exported, while other local and regional kinds are produced on an artisanal scale. It is still largely home-made in the north of Italy, where it is used for private consumption, especially after a big meal, or sneakily sold at restaurants…under the table. However, my translation of sketchy “country liquor” as “grappa fatta in casa” has been changed, through the standardizing policy of the editors, into the more sophisticated grappa artigianale (Bhattacharya, GADC 256). The latter bears the connotation of something gourmet, fairly expensive and appreciated by high-nose connoisseurs of distilled liquors. By contrast, in the passage in question, the character involved with grappa-drinking in KM is one of the Fyatarus, who are notably penniless and unrefined heroes.

What made the translation of boozing a 'translation impossible' in my Italian rendition of KM is the complex web of innuendos that in Bengali interrelate the kind of alcoholic drink, the class, caste, occupational group, religious and gender identity of the drinker, and the context of drinking. In the course of the novel, the neutral words to refer to alcohol (madya, mad), to alcohol drinking (madyapān karā), or to alcohol addiction (neśāgrastha), pertaining to a high register, and closely drawn from Sanskrit, are never used. Instead, a colorful and sophisticated range of informal expressions is employed. An important distinction, which is not familiar to Italian readers, but is pervasively implied in the novel, is the class distinction that underlies the drinking of deśi (the locally distilled toddy - referred to as Bāṅlā from the name of the brand, or as colāi, keoṛā, cullu, dāru) juxtaposed to the drinking of “foreign” booze (pharen, biliti māl, iṁliś). The former is consumed by the lower classes. It is cheap, it is not found in the governmental “wine shops”, and the quality of the home-made distillation is sometimes deadly.[24] The latter is expensive and imported: it refers to scotch, Indian whisky, brandy and to the fancy and relatively costly bottles that only the upper classes can afford. In between the two there is a third category of māl referred to with the paradoxical expression “country-made foreign” (e.g. Bhattacharya, KM 161), the foreign liquors made-in-India, an affordable solution for the middle-class, as the name of the most famous Indian whisky eloquently suggests: the “Officer's Choice”, or simply OC. The mutiny of the subalterns narrated in Kāṅāl Mālsāṭ is often plotted and set in the illegal and disreputable dives where toddy is sold (Bāṅlār ṭheke, in Bhattacharya, KM 34, or colāi-er ṭheke, ibid. 136). The Fyatarus move at ease within Kolkata following a precise mapping of watering holes where they can afford a “pāinṭ” (pint) of Bāṅlā even when they are left “with four rupees in the pocket” (ibid. 33). One of the Fyatarus is named D.S. after the cheap brand of Indian whiskey “Director Special.” The Choktars, the powerful Tantric-like marginalized superhumans who, together with the flying Fyatarus, coordinate the subalterns' insurgency, are regular Bāṅlā drinkers. For Bengali readers, this is clearly not a choice based on taste: it indicates that they stay with the poor and the destitute. For the Italian readers, the association of ideas that links local toddy with notions of marginality, illegality, subalternity and subversion can only become clear after a number of pages and occurrences. Some passages in the text make the relation between type of drink and social class more explicit, facilitating the translator's job and the reader's understanding. For example, in the eighteenth chapter, the Fyatarus get together at D.S.'s place. He asks his wife to take out the 'good glasses', and the other two Fyatarus understand that he is going to offer them something better than the usual bāṅluphāṅlu (Bāṅlā and the like): his brother-in-law has gifted him a bottle of Officer's Choice after the conclusion of a good deal in a sketchy business, saying: “Jamaibabu, enough of damaging your liver! No more crappy toddy (bāṅlumāṅlu)! From now on, I drink English (iṁliś) and you drink English, cause you're the Jamaibabu of the house”[25] (Bhattacharya, KM 161). To drink 'English' here is explicitly utilized as a class indicator and as a status symbol. Upper-class characters of the novel and people in positions of power only drink 'English stuff.' The doctor of the clinic where the baby Fyataru is born is used to drinking a peg of brandy every night (ibid. 80). The characters of the short story Maraṇ-dāṇ, traveling in first class on a long-distance train, share an exclusive bottle of Scotch (Bhattacharya Śreṣṭha Galpa). On the other hand, when the government realizes that something serious is happening in the underbelly of Kolkata, the police are ordered to keep strict surveillance on the places where most clandestine and rebellious activities can take place: whorehouses and illegal distilleries. The infiltrated 'mole' of the Fyatarus, a young, mistreated policeman who became their spy, sends them a secret message in code: “All M and CT under I” (ibidem 136). The message is decoded after a few lines: it is a warning saying that the secret agents have started to keep a close eye on hookers and bootleggers (M stands for māgi, a slang word for sex-worker, and CT stays for colāi-er ṭheke, a dive where cheap booze is sold). This encrypted message appears in the Italian translation as: "Tutte M e DC sotto O" – paraphrased after a few paragraphs: tutte le mignotte [Roman slang for prostitute] e le distillerie clandestine [clandestine distillery] sott'occhio [under eye]) (Bhattacharya, GADC 197).Similar to the way in which the class divide is reflected in drinking habits, a gender divide also emerges clearly from the drinking patterns in Nabarun's novel: a divide that does not surprise the Bengali reader, since drinking is substantially a gendered activity in India, but that may appear dissonant for the Italian readership, since light drinking is integrated in the daily life of both genders in Mediterranean countries.[26] Some scholars would define Italy as a ‘wet’ drinking country and India as a ‘dry’ one[27] (Wuytz et al). Moreover, drinking pertains to the male universe in urban Bengal: excluding a small (although increasing) section of educated and emancipated women, artists, intellectuals and upper classes, alcohol is a male business: drinking holes are places for men, and no woman can be seen at the governmental “wine shops” purchasing the bottles modestly wrapped in newspaper and handed across their prison-like barred counters. In the pages of KM, women characters never drink, and are never in the company of drinking men. The only exceptions eloquently describe which sorts of women are fit to drink and accompany drinking men in the collective imagery of Bengali society. The prostitute Kali fondly pours a glass of rum for Borilal – an ordinary shop-keeper with a passion for traditional Indian wrestling who becomes a sympathizer for the Choktar-Fyataru coalition – as he arrives in her hut (Bhattacharya, KM 82-83). An important woman character, Bechamoni, is part of the Choktar household and participates in Fyatarus and Choktars' gatherings, where drinking always accompanies their revolutionary conspiracies. Living outside of society and canonical gender norms, Bechamoni is a mystic and a medium with long dreadlocks, often described as possessed by spirits and portrayed while dancing with invisible ghosts. Another exception, at the opposite end of the hierarchical scale of social prestige, is Mrs Jwardar, the wife of the highest authority of the Police Department of West Bengal. When her husband is decapitated by a flying saucer “in such a precise and clear cut that Monsieur Guillotin would have been really proud of it” (ibidem 105), she recuperated her calm quickly, after a Patiala peg with a spritz of frozen water, which she usually drinks. Who would drink a Patiala peg? In the Bengali imagery, this is pretty clear: someone who is tough, because the Patiala peg is a big glass of liquor, a larger quantity than the size of a normal shot; and most probably, someone from North India, a Punjabi. The "Patiala peg" is supposedly a Punjabi invention and draws its name from the royal city of Patiala.Such connotations remain inevitably invisible in translation. For an Italian readership unfamiliar with the cultural context in question, a woman having a drink is neither the symptom of an outcaste nor an emancipated, upscale pastime. In the case of Mrs Jwardar’s favorite drink, I translated in Italian with the colorful and cheeky expression "un doppio cicchetto con uno spruzzo di acqua ghiacciata", meaning a double “cicchetto” (a colloquial term referring to an old, traditional kind of short shot glass for grappa or liquor, a snifter) with a splash of freezing cold water. The editors, faithful to their standardizing policy, changed the first part into a more neutral (and less interesting) "un doppio whiskey" (Bhattacharya, GADC 155), purging the text of its vernacular potency and its culturally embedded subversiveness.

The irreverent use of slang words for alcohol is a weapon that Nabarun employs to cut through the veil of moralism and hypocrisy. His characters are proud of being heavy drinkers. The poet-Fyataru Purandar Bhat is afraid of drinking liquor diluted with water, because then he may die at an old age, and his poems may end up being studied in school and printed in text-books (Bhattacharya, KM 162), which would be terrible for his image of a rebel poet. In one of the frequent quarrels between the Fyatarus D.S. and Modon, D.S. justifies not remembering a particular piece of information because he had been drinking too much; Modon asserts his superiority by saying: “Bullshit! You wouldn't even be able to swim your way through all the alcohol that I have drunk in my life” (ibidem 30). This attitude hyperbolically attacks the institutionalized bigotry in respect to drinking which is ubiquitous in West Bengal's dominant culture.

A particularly intense scene of Kāṅāl Mālsāṭ denounces the hypocrisy of such conservative views on drinking. On the day of Kali Puja, one of the most important festivals in West Bengal, all the liquor shops are rigorously closed, following the state prohibition on selling alcohol during particular days.[28] Far from solving problems of order and security, the prohibition only exacerbates the rush to stock up on alcohol beforehand. In Nabarun's description, on the day before Kali Puja the lines outside the liquor shops reach a length of three miles. The huts of the fishermen neighborhood are filled with illegal booze and fireworks, another banned commodity. In the cremation ground of Kalighat a crowd of ghosts is celebrating with loud and colorful fireworks. The police go for an inspection and realize that ghosts of gangsters, wrestlers, freedom fighters and local bullies are all engaged in the warfare-like explosion of firecrackers and in heavy drinking. The ghosts offer the policemen a share of their prasād[29]: a good imported Scotch and spicy mutton. The policemen, finding it impolite to refuse such a cordial hospitality, agree to remain for a couple of shots. They go back late at night to the police station, wasted and with hiccups, recommending to each other not to disclose this story to anybody, because it may damage their impeccable reputation (Bhattacharya, KM 50-54). This and many other episodes of Kāṅāl Mālsāṭ ridicule the high officers of the Kolkata Police, the target of most of the grotesque attacks led by the Fyatarus and Choktars.[30] Criticizing the corruption, the inefficiency, and the abuse and misuse of power of the police, Kāṅāl Mālsāṭ's enemies are arrogant policemen prone to drink while on service.

The ghosts encountered by the police commissioner invited him to participate in the “red hibiscus competition” (ibidem 52): a deadly mix of alcoholic drinks, called “the ancestor of cocktails”, is poured in a giant drum, where a red hibiscus, the flower offered to the goddess Kali, floats on the surface. In this and other passages of the novel, an implied connection relates the use of alcohol to the ritual sphere of Tantric religiosity, a connection that is unsaid and that remains obscure to the Italian readers who are not familiar with the popular representations of Tantrism in contemporary Bengal (Urban 162-164). The chief of the Choktars is reminiscent of a stereotypical Tantric guru performing occult and magic practices. He is accused of accepting a large circle of disciples so that he can get to drink all the booze that they bring as a sacred offering (Bhattacharya, KM 64). Nabarun Bhattacharya is certainly fascinated with the esoteric world of Tantric practitioners and their powers. I suggest that the reason lies not only in the Tantric use of alcohol, but particularly in the Tantric subversion of notions of purity and impurity, a subversion that rehabilitates classes of people otherwise oppressed by orthodox Hindu notions of purity and ritual pollution. The sacralization of socially forbidden substances and behaviors, both in Tantric practice and in Nabarun Bhattacharya’s novel, permits a ritual transgression that is liberating on both a cosmological and a political scale.

Conclusion

In this article, I tried to unpack some problematic issues that surfaced during my translation of Kāṅāl Mālsāṭ, particularly those related to the language of invisibility and marginality, the use of slang and the vocabulary of alcohol drinking. The profound cultural differences and social stratifications analyzed above require a tremendous amount of negotiation and jugglery in translation practices. They also require a lot of work on the part of readers and their strategies of meaning-making. These particular locations reveal how fragile is the extent to which we can look for or create “equivalents.” My translation sought to reflect the intentio operis (Eco) in the sense that my translation strategies are not entertaining the lay reader with a comfortably familiar language (“domestication”), commuting extraneous ideas into assimilated items; rather, I attempted to make the casual reader aware of a different social and cultural reality (“foreignizing”). However, KM is not a political manifesto: it is a playful and hilarious read, portraying ambiguous stances towards leftist ideology. It is an amphibious text, engaged in recreating the aesthetic regime of Bengali literature, projecting the reader into a fantasized metropolis, and appealing for political action, although with a bizarre and bitter undertone. Therefore, I avoided loading the reader with the burden of innumerable realia, 'untranslatable' terms that force readers to spend more time on Google Search and on the final glossary than on the pages of the novel they are reading. Besides that, there are also pragmatic dimensions of a translator's life, often under rigid and constraining contracts, to take into consideration. Is the editor of a commercial publishing house even going to accept a translation that, in order to 'be faithful' to its original text, employs neologisms, jargon, footnotes, realia and a lengthy critical introduction? The question in my case can be answered positively: yes, but only to a certain extent and after major 'domesticating' revisions.

Connecting the dimension of the text and its translation to the subjectivities and the expectations of a number of actors – author, translator, editors, readers, critics etc. - I suggested that a radical literary work – such as Nabarun's novel with its provocative language – needs a radical translation and a radical reader who accepts to resist the commercial politics of domestication. Resisting domestication and acceptability (Toury) in the translation process means to resist the assimilation of the source culture and language differences to the dominant culture of the target text, where the extreme end of domestication or “Westernization” can be seen as an incarnation of cultural imperialism, reflected through translation practices (Spivak 1993). In the light of reception studies, translation is not a communicative process that starts with source text A and ends with translated text B: it continues in the reader's response, and it has to do more with the reader's mind than with linguistic correspondences or with the functional goal of equivalence. A translation, embedded in historical and political reality, is a vehicle that transfers one message from one language and culture to another, in a setting where these two contexts stand at different power positions. The success of a radical translation can be seen as depending on a reader's openness, receptivity and curiosity. Translation theories have shifted their attention from translations' faithfulness to the readers' agency and their cognitive behavior, liberating the translator from the unsustainable burden of being the only vector of intercultural communicability, and bringing into play the translated texts' readers: their “interpretive communities” (Fish 147–174). The reader response ‘turn’ put much emphasis on the success or failure of aesthetic communication in translation based on the meeting of the “horizon of expectations” projected on the text. What still lacks elaborate discussion is, I suggest, a more sensitive exploration of the subjectivity of the translator that includes the translator’s “horizon of expectations” on her readers, their motivations and their engagement with the foreignness of the text. Such expectations on the part of the translator dictate many of the translator’s choices. These will be subjected again to the scrutiny of publishers and editors, who respond to the text in accordance with their own expectations, motivated by the readers’ consumption habits and the salability of the text.

Radical readers ready to embrace different aesthetic standards and sociopolitical settings are the ideal “interpretive community” who inspired and conditioned my translation practice. Implicit connotations, such as the class status of Bāṅlā drinkers – immediately available to the Bengali readers through shared collective imagery and cultural capital – are equally present in the Italian translation of Nabarun's novel, but grasping these requires an extra effort on the part of the Italian reader, an additional level of depth, and the readiness to discard and deconstruct assumed cultural notions to open up to different social realities: including the language of ghosts and the several – culturally relative – meanings of ‘booze.’

Notes