Figure 1 Figure 2

The Nation and its Discontents: Depicting Dissent during the Emergency

Supurna Dasgupta

“Democracy is the only system which makes room for, and respects, dissent.”

— Gour Kishore Ghosh, from prison

“My doodlings grew into some kind of a continuity- a clandestine human rights document until the very end of Emergency.”

— O V Vijayan (Tragic Idiom 256)

William Connolly suggests that at the heart of a nation-state lies the idea of a solid integrated kernel which is always lacking:

Any regulative ideal, surely, is impossible to realize fully. But the image of a nation seems to be marked by a sense that the density at its very center is both indispensable to it and always insufficiently available. This distinctive combination in the regulative ideal of the nation makes the state particularly vulnerable to takeover attempts by constituencies who claim to embody in themselves the unity that is necessary to the nation but so far absent from it. (81)

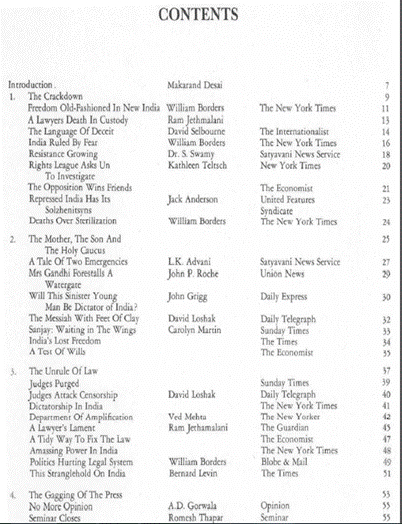

This “insufficiency” is the space where dissent thrives within the political imaginary of a centralized structure. So according to Connolly the nation (especially a democracy with its relative openness as opposed to its authoritarian counterpart), is incomplete without this countercurrent of dissent, which determines the status of political citizenship for the dissenter. The declaration of Emergency in a democracy, therefore, attempts to cut down the very scale of political citizenship to which the dissenting bodies seem to aspire. The Emergency declared by Mrs. Gandhi on the night of 25th June 1975 still looms menacingly in the history of the nation as the black hole of democracy: the initial unity of the peoples’ movement spearheaded by the JP counterpart was so thoroughly feared by the center that it unleashed unprecedented disciplinary measures such as the MISA (Maintenance of Internal Security Act) at once. The texts read in this article are excerpted from a particular archive which was inadvertently discovered by an Indian researcher in a US library, and the doodles of O V Vijayan in the context of more overt political cartoons such as those published in Satyavani and adverts like those brought out by Amul India.

A remarkable, though not surprising, feature of the Emergency was the way in which contemporary histories were distorted to produce false “facts”, one of the gravest dangers of “doing contemporary history” (Bipan Chandra 6). That Mrs Gandhi was moving steadily towards Fascism became evident in her aggressive response to even passive agitators, the Satyagrahi-s. An excerpt from Satyavani (also archived in the Chicago library) reads as follows:

(A)s the Emergency machine systematically closed every avenue of individual and public freedom, no casualty was bigger than Truth. Truth became a scarce commodity— you could not read it, hear it or talk about it. It had to be exchanged in secret, behind closed doors, and transported like contraband goods. The purveyors of truth had to learn the smuggling game.

(Makarand Desai, from the Chicago archive, Satyavani, 14)

This article presents a creative reading of two specific texts from the “victims” of this “smuggling game”. What were the forms of censorship and self-censorship adopted by these chroniclers of Emergency? What does the form of the diary convey or what is the value of belated testimonies in recuperating what Desai calls “Truth”? Does Vijayan encase his dissent in humour and naiveté in order to produce such doodles which would be all the more scathing for their childlike innocence? Is this the nation writing its own self into being: with its discontents?

PL-480: On Either Side of the Prison Bars

For most of the dissenting literature produced during the Emergency, censorship and/or self-censorship was the destiny. Yet, texts sought to convey what actual physical presence dared not. Edward Said claims that “texts convey the stammerings that never achieve that full utterance, the statement of wholly satisfactory presence [...]” (44) What value does the stammer hold: as a literary technique, the stammer is often used as a metaphor for incompletion and nervousness, the fear of enunciation itself. This enunciation, when it takes the shape of a personal journal or a dairy, begins manifesting ambiguous relationship which exists between writing and speech, that old dilemma which Derrida had alerted one to. What Snehalata Reddy’s diary or her daughter Nandana Reddy’s newspaper and testimonies achieve in terms of articulating dissent may be read as a continuing enactment of the near-equality of the two forms (speech and writing) which Derrida had proposed.

This near-equality is part of Derrida’s concept of arche-writing where the originary system of signs which precedes the binary of speech/writing is also susceptible to ceaseless alterations. Arche-writing, then, may be looked upon through the metaphor of an archive the volatility and authenticity of which is always suspect, whose modes of articulation is capable of myriad changes and which keeps revealing internal nuances that might radically alter the nature of its former manifestations.

Arkhe, we recall, names at once the commencement and the commandment. This name apparently coordinates two principlesin one: the principle according to nature or history, there where things commence-physical, historical, or ontological principle-but also the principle according to the law, there where menand gods command, there where authority, social order are exercised, in this place from which order is given- nomological principle.... The concept of the archive shelters in itself, of course, this memory of the name arkhe. But it also shelters itself from this memory which it shelters: which comes down to saying also that it forgets it. (Derrida, Archive Fever, 1-2)

Many of the texts used in this section of the article have been taken from an archive: hitherto hidden in the libraries of Chicago, recently uploaded for public perusal on an open blog. A note on the blog states:

These texts were contributed by Maya Dodd, Director of the Centre for South Asia at the Foundation for Liberal and Management Education, Pune. Maya Dodd’s PhD, ‘Archives of Democracy: Technologies of Witness in Literatures on Indian Democracy Since 1975′, among other things, dwelt on the literature produced during the Emergency of 1975 in India. Dodd revealed that the literature produced during the Emergency was easier to locate in University libraries in India that had systematically built up their collections in the 70s and 80s, than in the libraries of Delhi. In fact, texts that were sometimes unavailable in India could be traced in the library collections at the University of Chicago. All of these, she said, were stamped with the sign, PL480, Public Law 480, which allowed for the import of wheat from the US by India to be tied to the program for the acquisition of South Asian materials for American libraries. (5th September 2014)

The cited excerpt manifests the astuteness and rigour with which surveillance during and even after the Emergency sought to control the dissemination of information about State malpractices under Indira Gandhi and her son Sanjay Gandhi. Despite the cunning, some documents have survived: ranging from prisoners’ diaries, scrapbooks, pamphlets, underground journalism, letters, memorial anthologies, philosophical musings, manifestos and visual satire. This article will read only a section of a prisoner’s diary and her daughter’s testimonies. Nandana Reddy, daughter of arrested activist Snehalata Reddy, states the agenda of the underground movement:

The Underground Movement had a three-point objective: publicity in India to inform people of the existence of a real and widespread opposition to Mrs. Gandhi and to rouse them against the dictatorship; to keep continuous contact with individuals and organisations abroad, and secure the sympathy and support of individuals and organisations; and to organise spectacular acts of defiance to demonstrate that there was a live underground movement determined to keep Mrs. Gandhi and her Government off-balance and ultimately bring about her downfall. (Reddy 2015)

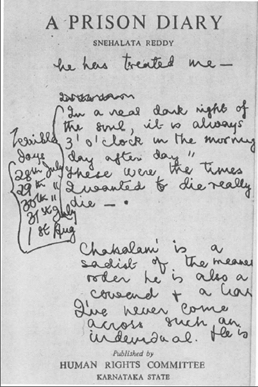

Ms. Nandana Reddy’s mother Ms. Snehala Reddy was an artiste, socialist and activist. The daughter recalls that during the Emergency they produced underground literature in a cyclostyle machine in their Madras house which also doubled up as a refuge for underground activists. She claims that this went on undisturbed until June 10th 1976 when in their absence their house was raided, leading to their arrest. Snehalata ensured their release in exchange for her own detention. Nandana says, “we realized that she had struck a deal” (2015, n. pag). Snehalata was eventually shifted to Bangalore Central Jail, detained under the MISA, where she was not allowed to meet any of the other political prisoners. Being the only female political prisoner, in nearly solitary confinement, her only companion was her diary, a facsimile of which has been preserved in this archive. (Appendix 1.a) The diary documents inhuman treatment of the detainees and absolute neglect of their deteriorating health. Strikingly, above a more generic diary entry spewing resentment about a particular member of the prison community (perhaps a warden), she scribbles a particularly evocative statement, “In a real dark night of the soul, it is always 3 o’ clock in the morning, day after day. These are the days when I really wanted to die.” (A Prisoner’s Diary, Chicago archive) Interestingly, this melancholic lyricism is also accompanied by a keen self-consciousness of the value of the diary as testimony: the candid marginalia to those lines state “Terrible days- 28th July, 29th July” etc (Ibid.).

This juxtaposition of multiple moods and genres within the testimony itself begs the question about the epistemological value of the testimony. The testimony defines itself by not being a part of print culture although it seeks to enter into the range of notice through other media like interviews and cyberspaces. Snehalata’s self-conscious recording of her experience alerts the reader to the personal voice of a public figure suffering from the continuing trauma of violence. Snehalata’s diary has all the usual markers of testimony such as repetition, continued reliance on memory even as she realizes its susceptibility to distortion, and assiduous recording of details such as dates and letters, as though already anticipating the political valency of this act of self-interviewing in the annals of history.

The very materiality of the diary as an object arouses an affective register: this is the part of a bodily trace of a political prisoner where the exteriority of the body and the interiority of the psyche seems to have come together. As a literary scholar or a book-historian this is of specific interest to me since one can only read such a text with a certain kind of speculative materialism as methodology: neither hooping for the absolute empiricist sense of “raw” historical data, nor expecting to reach historical epiphanies through the near-existentialist sighs of a detainee. Such a method is not without its pitfalls. Unlike an autobiography, a diary entry cannot be read as a retrospective text: yet the fact of spontaneity does not often mean taking recourse to literal meaning-making. The truth is often hidden behind textual strategies such as abstraction, alteration of names, generalization of specific reactions. The reflection of life in a diary is different from the mirroring that takes place in the autobiography: the principle of selection in the latter form encounters the banal and the private in the former. “It is like trying to make a sponge fit a matchbox … Before becoming a text, the private diary is a practice. The text itself is a mere by-product, a residue. Keeping a journal is first and foremost a way of life, whose result is often obscure and does not reflect the life as an autobiographical narrative would do.” (Lejeune 31)

The historical and literary value of the private diary is precisely the fact that it is bound to be idiosyncratic. Yet the sheer unreliability of such a document cannot be adequate grounds for its dismissal as testimony to lived experiences: “testimony is a source of warrant in itself, not reducible to warrant derived from other sources even if empirically dependent on them.” (Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy) Veena Das allows for three paradigms of concern while reading testimonies as historical documents: the question of detail, the language of law and the language of memory, and the power relation between the outsider and the affected party (5). Snehalata’s prison-diary was eventually published by the Human Rights Committee of Karnataka State, available copies of which were summarily shipped off to Chicago. The details in the diary such as how the interviews were held bear witness to the gruesome treatment meted out to the inmates:

I believe you came to inquire. I'm sure I must be quite old-fashioned, I thought inquiries were held differently— I have never heard that the tormented are questioned before the tormentor! These methods must be rather new—maybe something that Delhi has acquired and you imbibed in your recent training. If yesterday's was a real inquiry, then you are a very good actor—I must recommend you to my husband. Yesterday was a "mock inquiry". Why were the girls not asked individually so that fear could be removed from their minds?

(A Prisoner’s Diary, Chicago Archive)

One wonders what juridical space this language has before a court of law: the irony behind such a speculation is of course the tragedy that Snehalata was never allowed a trial until her parole during which she passed away. Her diary remains a curious mixture of the antechambers of public history, sometimes tempered by the personal moment of deeply secular confession. The diary remains a marker of the standards of justice which the Emergency sought to reconfigure.

At the other end of the public-private spectrum, justice was still the Holy Grail in search of which a few newspapers such as Himmat continued functioning well into the Emergency. Kuldeep Nayar, who was arrested during the Emergency for his refusal to acquiesce to the Press Censorship, comments: “The failing of the press was also the failing of independent India.... The reason why the emergency is a watershed is the abject manner in which the pressmen caved in.” (2008 58) Kalpana Sharma, founder-member of the group of journalists who ran the show at Himmat, recalls that the government had sent them some guidelines about Press content: “Number one on the list was: “Where news is plainly dangerous, newspapers will assist the Chief Press Adviser by suppressing it themselves. Where doubts exist, reference may and should be made to the nearest press adviser.”” (2015 n.pag) The pamphlets in Advani’s scrapbook are largely incisive, urging the masses to rise in protest against the suppression of civil liberties. The musings on passive resistance in Acharya Kriplani’s work read like a deep sigh about the future of democracy. Along with these, the open letters and the texts of forbidden public speeches from other resistors all produce the semblance of an actual discourse about the scale of civil freedom which the Emergency sought to curtail. These texts, much like the diary, almost have a vocal quality, producing the illusion of democratic equality between the “speaker” and the “hearer.” In a similar context, Said says

In producing texts with either a firm claim on or an explicit will to worldliness, these writers and genres have valorized speech, making it the tentacle by which an otherwise silent text ties itself to the world of discourse. By the valorization of speech, I mean that the discursive, circumstantially dense interchange of speaker facing hearer is made to stand- sometimes mistakenly- for a democratic equality and co-presence in actuality between speaker and hearer. (45)

This speech is ontologically different from the kind of voice which one had heard emanating from Snehalata’s diary. Her diary had the anger of personal correspondence, the confusion of introspection. It also had the quality of a soliloquy, which is aware of its audience only at a meta-cognitive level. The rest of the Chicago archive, including the scrapbooks, was waiting to be voiced, after the fashion of public oratory.

The nostalgia for democracy can be clearly sensed in the very opening pages of journalist Kuldeep Nayar’s recollections of the Emergency with his dedication “to the people of India - the only ones who could and did” (1977 i) Sita Bhatia reports that “In contrast to the performance of the daily press, the serious periodicals of the country displayed remarkable guts and dragged the Censor board before the High Court.” (191) The Press Council was dissolved and the Government passed the Publication of Objectionable Matter Act.

What was at stake was the very form of democracy: despite the Congress’ clarion call for Garibi Hatao it was hardly a programme which gained any sort of spontaneous grassroots support. On the other hand, the Janata Party manifesto, with its image of the peasant-labourer (Appendix 1.c) claimed an agenda to give “the people bread and liberty” and “the country stability with freedom”. In the context of the form of democracy offered by either party, Balraj Puri, who was a critical advocate of JP, speculates,

Acharya Kripalani was equally concerned over the future of democracy in India. "If people do not submit themselves to voluntary discipline," he warns, "they cannot escape the consequent imposition of totalitarian discipline."' How can what Gunnar Myrdal called a soft democracy or functional anarchy be made a disciplined, dynamic and efficient system capable of delivering the goods the common man has come to expect of it? How can the system be made to function even by and for human beings as they are - and are likely to remain- and not as they should be? (1743)

It remains to be asked what exactly “voluntary discipline” entails. At a time when journalists realize “that freedom of the press is not a luxury that the rulers bestow on you: it is a lifeline in an unequal society like ours. Without it, the poor would become invisible because it would deprive them of their basic right to be heard as citizens in a democracy.” (Sharma 2015); what forms of (self-)discipline are acceptable? Does the prison-diary have more sense of self-discipline than the newspaper? Can the irreverence in the diary be more radical than the lip-service of public speech? Is it necessary, for the sake of democracy, to unlearn reverence?

“Encasing Hostility in Humour”

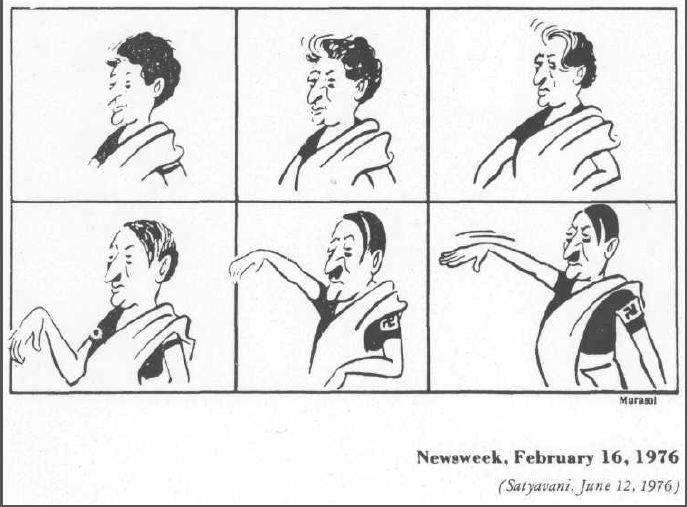

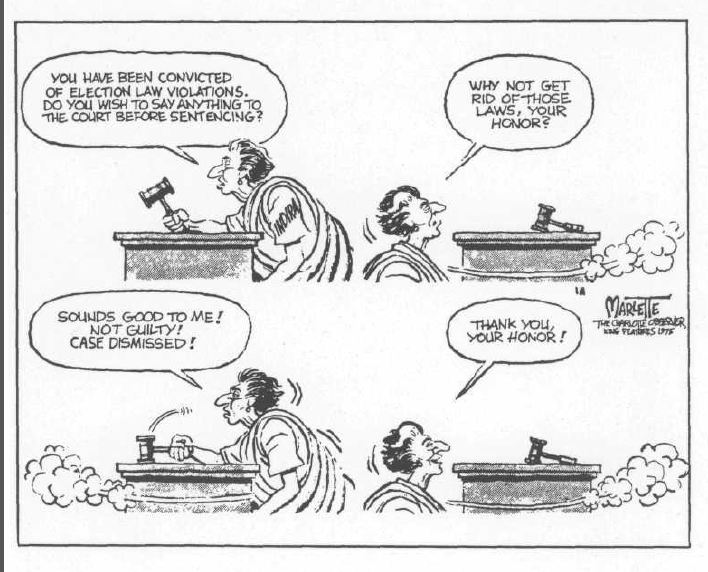

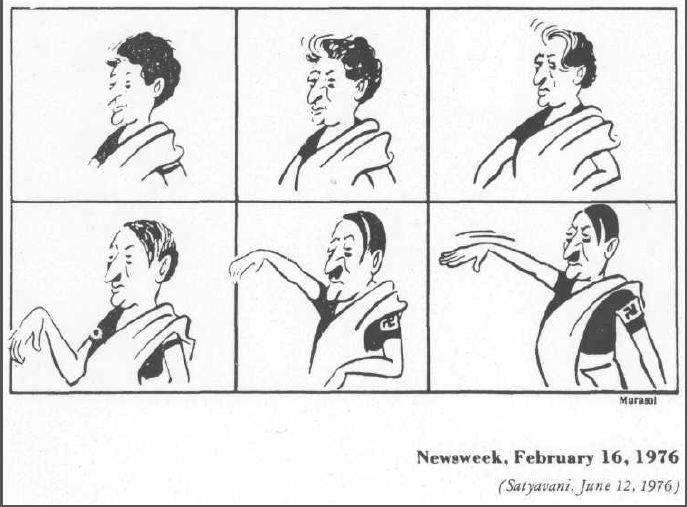

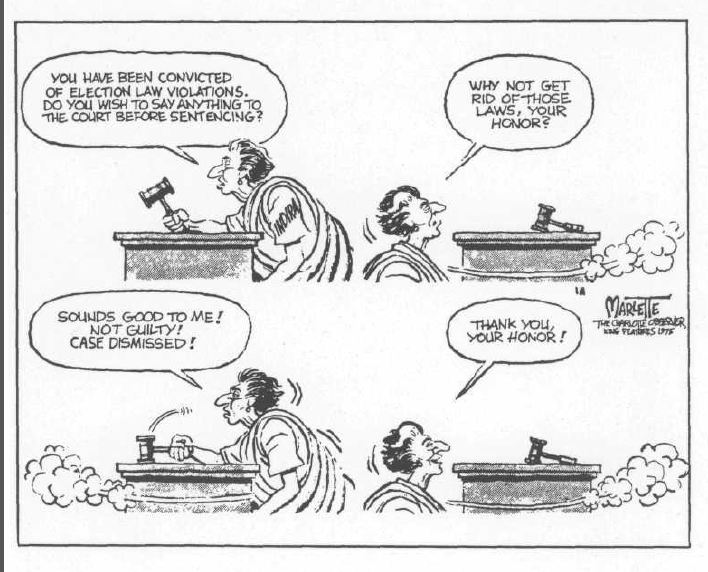

The veteran political cartoonist Abu Abraham concludes his essay “Anatomy of the Political Cartoon” with the following anecdote. “James Gillray, the 18th century English cartoonist, one of the finest exponents of the craft, was described by a contemporary journalist as a “caterpillar on the green leaf of reputation.” Long live the caterpillar!” (279) Indeed, in a democratic state, the role of the political cartoonist is to thrive on reputation: for the sake of its fodder as well as for the sake of critiquing the host! In that sense, the Emergency provided the political cartoonist with the perfect opportunity to whet his appetite: to put his art to the use of exposing the underbelly of false reputation, and to destabilize through humour the very serious claims of stability that the State seemed to make. In fact, Satyavani carried two following cartoons, one by Murasoli (1976) and one by Marlette (1975).

Figure 1 Figure 2

While in Figure 1, the gradual transformation of Indira Gandhi to Hitler is being traced; Figure 2 records the “proceedings” of the “court verdict” presided over by a mirror-image of Indira as the judge, followed by an annulment of all law altogether. The two cartoons, together, project the image of Mrs. Gandhi as the perfect Fascist, consolidating her dictatorship over what was the largest democracy in the world. The hexa-panel in the first one traces the gradual shift from the leader of the masses (hence nameless) to the gradual acquisition of megalomaniacal powers (denoted by the Nazi badge) to the female counterpart of the signature pose of Adolf Hitler. Mrs. Gandhi is thus positioned in a lineage of world dictators: the ones who start with the socialist garb and popular support and eventually metamorphose into Fascist demons with a lust for totalitarian power. Gombrich and Kris claim that demonstrating the stages of the caricaturist’s art is also a metaphor for the transformation itself:

“A single feature often stands for the whole, and a person is represented by one salient characteristic only. To the caricaturist, however, this extreme simplification is not the starting-point of his work. He arrives there often by stages, beginning with a lifelike portrait which he somehow distorts and simplifies in the absence of the model.” (322)

The second figure proceeds like a comic strip with a single actor as though a monologue is being depicted in the visual medium: the irony lies in the fact that the Judiciary (who is a mirror-image of Indira) passes a sentence on her own erasure. The State Emergency is exposed to be eradication of the blind (therefore egalitarian) arms of justice substituting it with the whims of the dictator. Such acts were to be investigated and taken to task by Justice Shah. Yet Katherine Frank, Mrs. Gandhi’s biographer, remarks on the disappointment which the report was since “it contained only a fraction of the Shah Commission hearings... (and) survives as the only official record of the Emergency because the full tape-recorded versions of the Commission have vanished.” (1439) So if read in conjunction with the Shah Commission Report, this cartoon may be perceived as an even sharper indictment of the outrageous impunity with which Mrs. Gandhi sought to wish away the judiciary.

What must be noted is that both these cartoons were first published outside India: one in Newsweek and the other in New York Times. Censorship was so intense that most of the articles and cartoons that Satyavani sought to print had to be outsourced (Appendix 2.a) and (re-)printed in utter secrecy: the post-printing exodus of documents to the US bears witness to the scale of threat these posed to Indi(r)a. Amul brought out its signature Amul girl ad-toon only in 1977 after the Emergency was lifted, for fear of the State’s wrath: referring to the two most resented phenomena during the Emergency: one regarding the MISA (Figure 3) and the other regarding the compulsory vasectomy drive started by Sanjay Gandhi (Figure 4).

One can already note the self-censorship which Amul engages in by maintaining a non-committal stance in both the adverts. Instead of direct castigation, these adverts remain as reminders of a more stringent time in independent India’s national history. Amul seems to have contributed to a visual journal of the nation: the life-writing of a nation through graphic satire, supplementing the textual counterparts and lacunae in the diary of Mrs. Reddy which also straddled the cusp between public and private life-writing. Both engaged in an optimum amount of self-censorship but were also equally self-reflexive about their status as historical documents.

It is through this prism of creative self-censorship that one might arrive at the vantage-point from which Vijayan’s art becomes more apparent. Self-censorship has a strange mix of the conscious and the unconscious. Gombrich and Kris argue “A painter whose interest in caricature is evident is unable to make convincing caricatures so long as he distorts his own personality. The unconscious self-distortion has taken the place of the distortion of his models.” (340) Yet it was impossible to publish caricatures and/or cartoons with any sort of political import without the express permission of the Censor Board. Many of Abu’s cartoons were restricted to private viewing only (Appendix 2.b). O V Vijayan, though thoroughly critical of the Emergency, therefore took recourse to the form of the speechless doodle.

Vijayan was of the opinion that “Even though cartoon is not editorial it certainly is editorial commentary. It is criticism presented in crisp words and in sharp symbolization of the drawing.” (14) Here he is in agreement with Lawrence Streicher who states that “Caricatures interpret nations, figures and events and help to supplement the news presentation with statements of meaning.” (438) But what happens when the editors begin to yield to the pressures of the Censor board? How does one continue to publish? One takes recourse to the fabular and the metaphoric. Vijayan prefaces his Emergency doodles with a short written piece depicting a mythical anarchic kingdom - one can easily recognize Mrs. Gandhi as the “President” who howls “O, they will sack my children, they will sack them all!” (242) One also engages in self-conscious self-censorship such that the innocuousness of the open-ended art of doodling protects the cartoonist from the disciplinary measures of the State.

Michael G. Levine cites Freud to illustrate the mechanism of self-censorship. Quoting from The Interpretation of Dreams, Levine suggests:

“All dreamers are equally insufferably witty, and they need to be because they are under pressure and the direct route is barred to them.”(Freud, 371) The contrast here is clear enough. While the dreamer is obliged to be overly clever, the writer [...] simply cannot help himself. While the former uses circumlocutions to get around obstacles, the latter merely "lapses" into them. While the creative, wish-constructing part of the dreamer works in tandem with its censorial counterpart, in the author the hand that evaluates "unfortunately" has nothing to do with the one that produces. (168)

Levine goes on to make further connections between the act of writing, the condition of repression and the reflections of Derrida on Freud:

Freud says, to appreciate fully the comparison of the writing pad to the functioning of the psychical apparatus, we need to "imagine one hand writing upon the surface... while another periodically raises its covering sheet from the wax slab" (S.E. 19, 232). Derrida reads this scene of two-handed writing described by Freud as gesturing toward a different kind of relationship between writing and repression, one that may no longer be understood simply in terms of the alternating logic of "on the one hand, on the other." To follow the movement of these hands is, in other words, to approach writing and repression as processes that are at once more intimately connected and more internally divided than has hitherto been imagined. It is for this reason that Derrida speaks of both "the vigilance and [the] failure of censorship." (171)

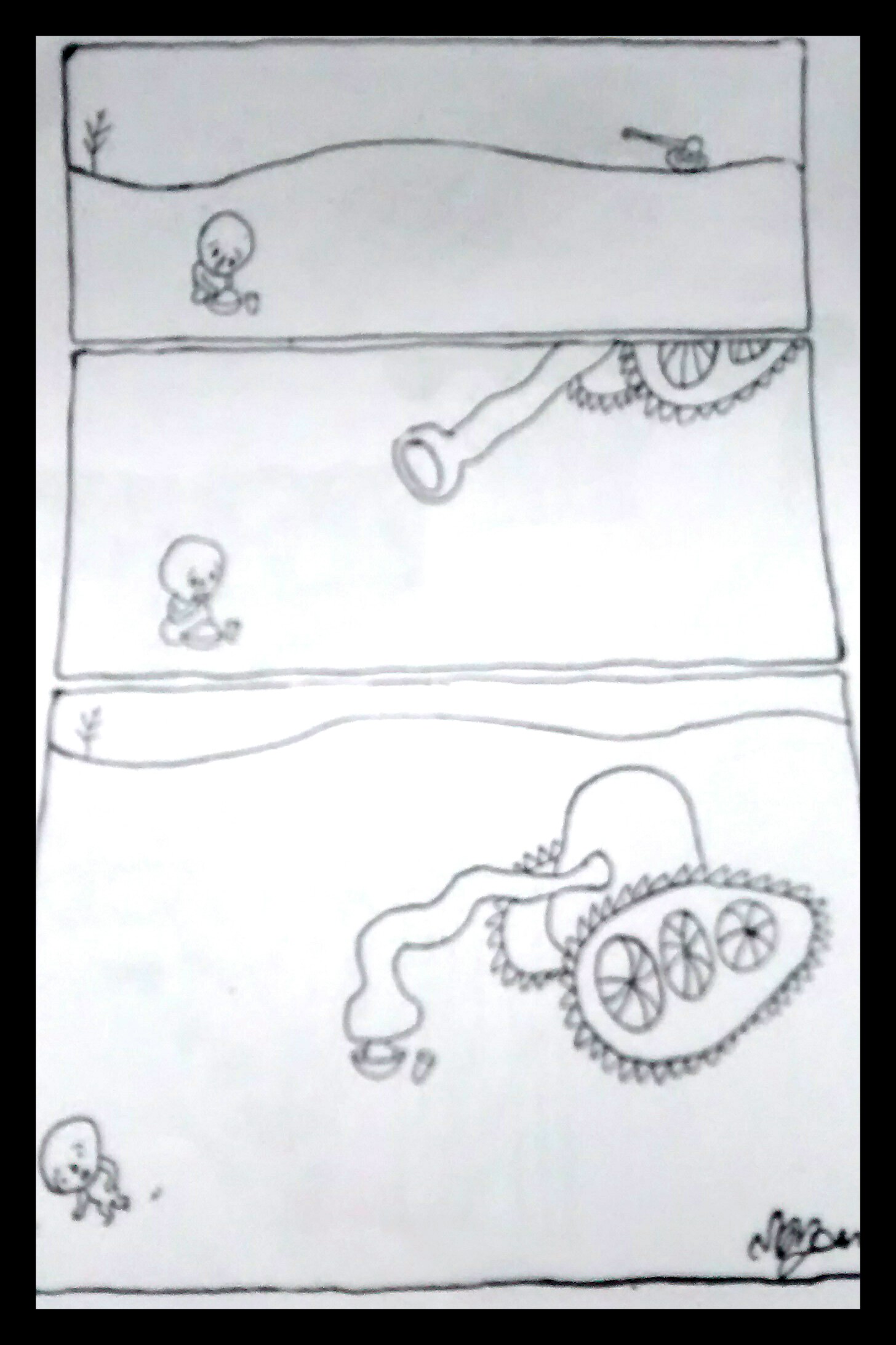

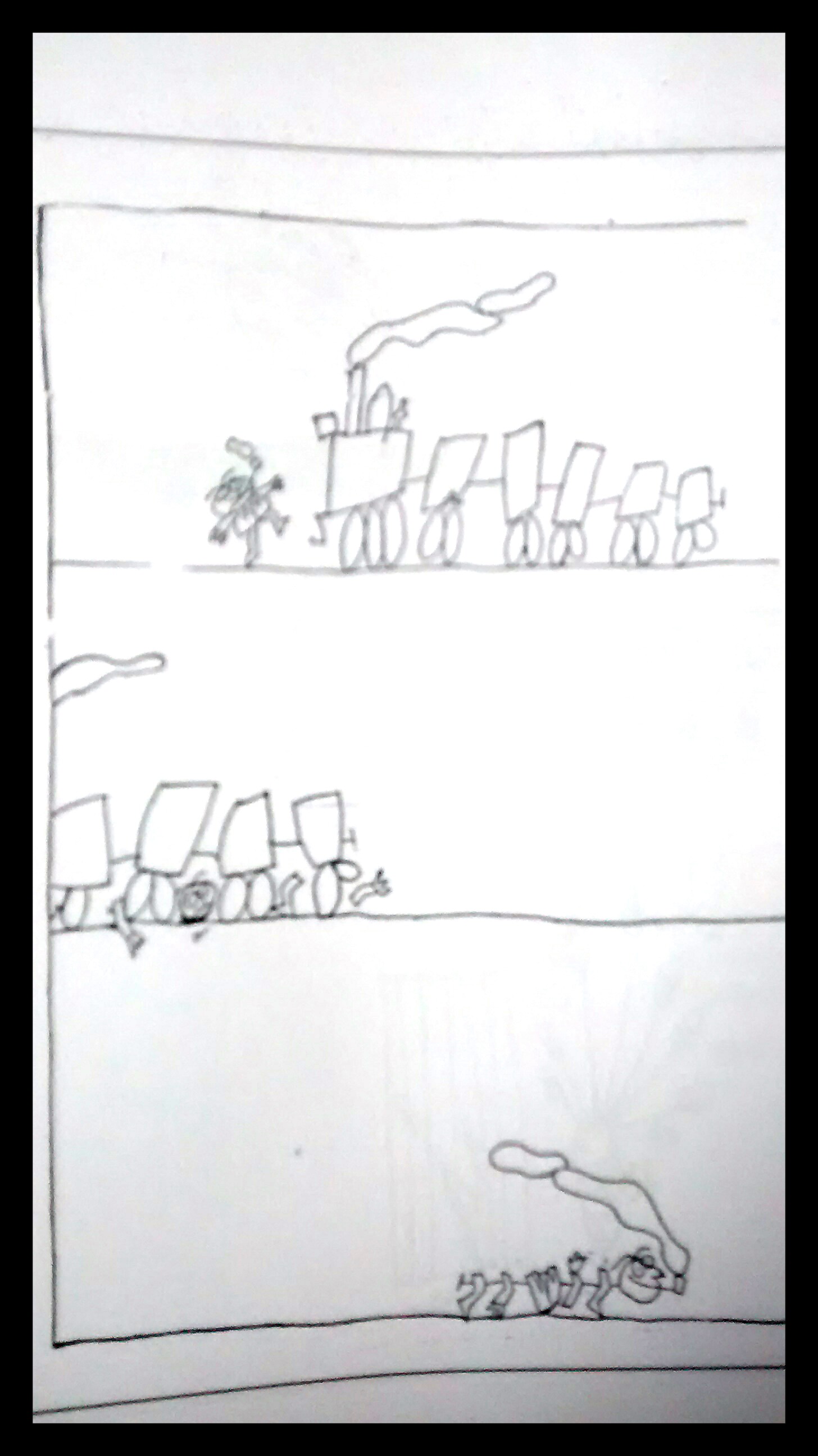

The doodles by Vijayan betray a similar dialectic between repression and expression. Almost all of them come in a series comprising two or more units, after a narrative fashion. The burden of expression shifts from the caricaturist to his characters, in their gestures and in silence.

Figure 5.a refers to the voluntary submission of the intelligentsia and the bureaucracy to the dictator, as they dispose of their heads and blindly march behind the smug leader. Figure 5.b depicts the incentivized mindless warfare that can be declared on the other by the sly dictator. Both these cases correspond quite directly to the kind of human rights violations that were taking place during the Emergency. Figure 5.c is quite obviously a satire on compulsory vasectomy. But this one is a layered metaphor. Not only is this a reference to the vasectomy, but in depicting the bird bearing the olive branch being forcibly/surgically taken out of the intestines of someone dressed like the military, Vijayan has made a secondary reference to the involvement of the Army in “peace-keeping” projects during the Emergency.

Fig. 5.d Fig 5.e

Figure 5.d is a cruel mockery of the futility of the anti-poverty drive or the Garibi Hatao as food is snatched away from the child by the tentacular arm of a nuclear tank. Finally figure 5.e may be read as the dismemberment of the country/ordinary citizen by the locomotive of development (which ironically has a cross and a tombstone on its front coach), but the former threads its parts into a whole and gets moving, imitating the motion of the train in the previous two panels. Ironically though, this recuperated body-as-train moves in the opposite direction: gesturing at the recession/regression/setback that mindless industrialization and development usher in. This is the forcible “pacification” and “integration” of the country and its people which must fall in line with the pace of globalizing forces such as industrialization, anti-population measures and nuclear deals, even if at the cost of human lives and caste/communal violence.

A similar “pacification” of the cartoonists and the journalists was attempted during the Emergency. Vijayan, who refused to fall into line, but needed to survive, took to doodles which hang midair, between metaphor and material, knowledge and nonsense. Matthew Battles claims rightly in his essay “In Praise of Doodling” that “the doodle maybe strange- but it does not bark, and it knows the secrets of the deep.” (106)

What is truly radical about Vijayan’s doodles is the method he chooses about these “secrets of the deep”. There is something childlike, almost childish in his lines. As opposed to the detailed cartoons with well-defined lines and figures in his other work, here Vijayan seems to have taken recourse to the methods of what has often been identified as “naïve art.” Also termed “Innocent art” or “Outside art”, this is characterized by a childlike simplicity of vision and execution. Naïve art is conventionally associated with a certain kind of romanticism which attempts to move away from the sophistication of “culture” towards the “primitivism” of a pre-civilizational innocent past. Oto Bihalji Merin comments on the cultural dehistoricization of naïve art through a temporal prism claiming that naïve art “has outlasted the ever-changing variety of aesthetic styles, ... [remaining] an essential part of the ... [art] scene in any period.” (2015 n.pag) In that sense, the usage of naïve art as a method to criticize the state is a multi-layered attack with multiple efforts at self-censoring.

For instance, the figure of the child in many of these doodles is the very image of innocence: the kind of radical innocence that can shake the conscience of a nation. But more significantly, there is a radical innocence in the adopted form too—one which is characterized by a lack of history, a lack of context. Naïve art is the most historical when it seeks to dehistoricise itself. By refusing to draw recognizable figures seriously, and portraying almost comic-book images of generic figures such as the soldier, the stick-human crowd, the child with an emaciated body and an overgrown head, the smug leader, Vijayan has attained the perfect balance of “writing and repression” which may also be found in the Freudian description of self-censorship.

The fact that this school is also termed “Outsider Art” or art brut gestures at a further nuance within this self-censoring. Dubuffet says:

Those works created from solitude and from pure and authentic creative impulses– where the worries of competition, acclaim and social promotion do not interfere- are, because of these very facts, more precious than the productions of professionals. After a certain familiarity with these flourishings of an exalted feverishness, lived so fully and so intensely by their authors, we cannot avoid the feeling that in relation to these works, cultural art in its entirety appears to be the game of a futile society, a fallacious parade. (32)

The non-interference of the method encounters the interventionist cartoonist in Vijayan who adopts it as a mechanism to censor his own expressions. As even the “fallacious parade” of the professional cartoonists came under surveillance, Vijayan infused “these flourishing of an exalted feverishness” with the despondency of his contemporary situation. What emerged as a product was morbid laughter behind which was the world-weariness of the common man.

Moreover, as one who is an “outsider” to the artist’s canon, the naïve artist can effectively evade the axe of the art-censor. At the same time, along with the politico-judicial freedom of the outsider, comes the artistic freedom of the doodling cartoonist. The value of the generic extends the perimeters of his critique to stretch beyond the immediate, and hits out at every authoritarian state with the same childlike innocence and childish impetuosity. Self-censorship then becomes an act of self-emancipation. This is the great contribution of Vijayan to the canon of cartoonists in modern India. By “relegating” caricature to the doodle, he elevates it beyond the immediate: never blunting the edge, but effectively saving his own space to scratch away upon tablets of time.

“Anthropology of this Censorship”

Forty years from the Emergency, truth is still the casualty of censorship in India. So, a question from Lawrence Streicher continues to bear relevance: “Where is the truth between the caricature and the news column? What kinds of truth are appropriate to be selected for consideration when one reads a newspaper and where are they to be found?” (439) Sudipta Kaviraj opines that it is this evasion of truth which a Nehruvian statesman would have rued. A turn away from truth is also a turn away from the people and their institutions (120).

Arvind Rajagopal claims that Emergency was a watershed in the post-independence history of the democracy: how it re-defined the nature of political citizenship for the middle-class, who, in the lack of identification with the state, chose to overlook contingencies of labour.

Governance in the aftermath of the Emergency placed an overt reliance on consent over coercion, but in ways that are themselves significant. Categories of culture and community, and related forms of social distinction, gained in importance over earlier developmental distinctions premised on an authoritarian relationship between state and the people. The change meant a shift away from the Nehruvian focus on the economy as the crucial arena of nation-building, involving labour as the key modality of citizenship. Instead, culture and community became the categories that gained political salience in the period of economic liberalization. The mass media were central to this redefinition of the political, multiplying in size and reach, and acquiring market-sensitive forms of address couched in the rhetoric of individual choice. These events, I suggest, are critical to understanding the formation of the new middle class in India, as a category that increasingly defines itself through cultural and consumerist forms of identity, and is less identified with the state. (1004-5)

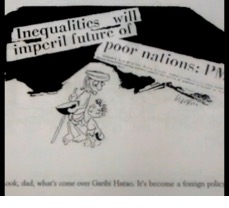

Figure 6

This middle class has arrived with its own sense of censorship: defined by the new forms of mass media, this class has de-prioritized economics as the victim of bad governance, prioritizing culture and community instead. Moving away from the Indira-brand of authoritarianism, they have also moved away from some basic tenets of an egalitarian Nehruvian democracy. Some of Vijayan’s cartoons, then, ring as true for the Emergency as for the post-liberalization India. The world-weary father (ostensibly from the labour-class, without any markers of community) looks on as the child with a radical innocence exclaims “Look, dad, what’s come over Garibi Hatao. It’s become a foreign policy.” (Figure 6, below, from Tragic Idiom)

The Emergency, then, although thoroughly critiqued by the contemporaneous middle-class intelligentsia; has paved the way for a middle class whereby the country has moved away from expressing dissent against top-level incompetence towards shaping itself into the mould of the exclusivist and individualist liberalism which Vijay Prashad has rightly identified as the epicenter of modern Fascism (1996).

If the Emergency necessitated documenting popular dissent in times of censorship, post-Emergency India needs to learn how to avoid the co-option of dissent by facile liberalism. The nation needs to re-write itself through the idioms set by its predecessors: a creative reading of the diaries of political prisoners would provide the language of caution and activism peppered with references to the psychic life of the individual, while a formal stylistic reading of cartoons and doodles would alert the contemporary reader at modes of self-censorship which are not mere limits on one’s speech but also an elevation of the right to critique through other means.

Appendix 1.a: Facsimile of Snehalata’s Prison Diary

Appendix 1.b: Satyavani

Appendix 1.c: Janata Party Manifesto

Source: The contents of the Appendix (1.a-1.c) have been taken from the Chicago archive, available at https://publicarchives.wordpress.com/full-text-collections/emergency/. For further details, please refer to the works cited section in the end.

Appendix 2.a: Details of original publication for the re-printed articles in Satyavani

Appendix 2.b: Abu’s censored cartoons which were published in Games of Emergency 1977

Source: The Chicago archive from which Appendix 1.a-1.c had been taken.

URL: https://publicarchives.wordpress.com/full-text-collections/emergency/

Notes:

I am not referring to the philosophical school by the same name propounded by Meillassoux per se, but operating within the same framework to some extent. This means that I wish to posit the ‘facticity’ of the material object (the diary in this case) as hanging between material and metaphor, attempting to expand the perimeters of its symbolic and/or metaphysical value, while also never forgetting its material existence within a network of circulation.

All images for Vijayan taken from Tragic Idiom

Works Cited:

(Anon.) "Emergency 1975." 5 September 2014. Archive and Access. 29 May 2015. Web.

Abraham, Abu. "Anatomy of the Political Cartoon." India International Center Quarterly, 2.4 (October 1975). Pp. 273-79. Print.

Battles, Matthew. "In Praise of Doodling." The American Scholar, 73.4 (Autumn 2004). Pp. 105-8. Print.

Bhatia, Sita. Freedom of Press: Politico-Legal Aspects of Press Legislations in India. New Delhi: Rawat Publications, 1997. Print.

Bihalji-Merin, Oto. What is Naïve Art. Gina Gallery of International Art. 5th December 2015. Web.

Chandra, Bipan. In the Name of Democracy: JP Movement and the Emergency. New Delhi: Penguin, 2003. Print.

Connolly, William. Why I am Not a Secularist. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999. Print.

Das, Veena. "Anthropological Knowledge and Collective Violence: the riots in Delhi, November 1984." Anthropology Today, 1.3 (June 1985), Pp. 4-6. Print

Derrida, Jacques. Archive-Fever: A Freudian Impression. Trans. Prenowitz, Eric. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1995. Print.

- Of Grammatology. Trans. Spivak, G.C. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 1974. Print.

Dubuffet, Jean. “Make Way for Incivism”. Art and Text, 27. (Dec 1987-Feb 1988): 32. Print.

Frank, Katherine. Indira: the Life of Indira Nehru Gandhi. New Delhi: Harper Collins Publishers, 2002. Print.

Gombrich, E H (with Ernst Kris). "Principles of Caricature." British Journal of Medical Psychology, 17 (1938). Pp. 319-42. Print.

Jeetu. "...the way it went for 20, the AMUL way." 12 October 2008. Jeetu's Shared Memory. 29 June 2015. Web.

Kaviraj, Sudipta. The Imaginary Institution of India. New York: Columbia University Press, 2010. Print.

Lejeune, Philippe. On Diary. Ed. Jeremy D. Popkin. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2009. 226. Print.

Levine, Michael G. "Freud and the Scene of Censorship." Burt, Richard. Censorship, Political Criticism and the Public Sphere. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1994. Pp. 168-91. Print.

Navasky, Victor A. The Art of Controversy: Political Cartoons and their Enduring Power. New York: Random House, 2013. Print.

Nayar, Kuldeep. Emergency Retold. New Delhi: Konark Publishers, 1977. Print.

- "Sixty Years of Press Freedom: Emergency, a Watershed." Media Mimaansa (Jan-Mar 2008). Pp. 57-60. Print.

Prashad, Vijay. "Emergency Assessments." Social Scientist 24.9 (Sept-Oct 1996). Pp. 36-68. Print.

Puri, Balraj. "Fuller View of the Emergency." Economic and Political Weekly, 30.28 (July 1995). Pp. 1736-44. Print.

Rajagopal, Arvind. "The Emergency as Prehistory of the New Indian Middle Class." Modern Asian Studies 45.5 (September 2011). Pp. 1003-1049. Print.

Reddy, Nandana. "How the Emergency Took My Mother Away." The News Minute. 25 June 2015: Web.

Said, Edward W. The World, the Text and the Critic. London: Vintage Publications, 1991. Print.

Sharma, Kalpana. "Himmat during the Emergency: When the Press Crawled, Some Refused to Even Bend." Scroll 23. June 2015. Web.

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Epistemological Problems of Testimony. 2012 August 2012. 20 June 2015. Web.

Streicher, Lawrence. "On a Theory of Political Caricature." Comparative Studies in Society and History, 9.4 (Jul 1967). Pp. 427-45. Print.

Vijayan, O. V. Tragic Idiom. Kottayam, India: D C Books, 2006. Print.

Supurna Dasgupta

University of Delhi

supurnadg@gmail.com

© Supurna Dasgupta 2016.