Sex and the Aesthetics of the Vulgar: Reading the Creative Paradox in the Works of Robert Crumb

Purba Chakraborty

In the present time, the waves of the #MeToo Movement have sufficiently brought under rigorous scrutiny modes of sexual expression and sexuality in general. Under such circumstances the cultures of sexuality around us need a revisit. Especially in the field of art and literature, the delicate dynamics among artistic expression, readers’ response to it, and the general ideological climate under which the piece of art was created comes under a new critical lens as we become aware of the possible signposts of misogyny in them. It becomes difficult to discuss this creative matrix, because each category in this ‘triad’ is absolute variable, depending on the ever-changing contours of time and space. In the present context, the paper intends to reflect on the works of Robert Crumb who has received both appreciation and stark criticism, making his position ambiguous in the history of comics studies.

Now more than ever it becomes crucial and relevant to talk about Crumb not only because of his unconventional modes of expression which often verged on the levels of obscenity and seemingly outright misogynistic, but also because of the curious reason why he chose the very particular mode of sexual objectivity in his works that may be termed as pornography by some. His comics attempt to embody time of their production—the American Counterculture of 1960s and 70s. Creating at the heyday of the American Countercultural scene, Crumb reacted not only to the existing social, political and economic scenario, but also the mindless and facile comics practices in America and in doing so he single-handedly spearheaded the Underground Comix Movement.Thus they abounded in a free fervor of sexual freedom, psychedelic visions fostered by LSD, jazz music, and an ideological sympathy for the New Left ideals, to name a few. It would be interesting to note the ideological repercussions of reading the works of Crumb in the light of the new #Metoo movement which has driven home a new awareness about the dynamics of sexuality at play in our society at large. The #MeToo is a phrase first used by Tarana Burke and has been defined as “a movement that deals specifically with sexual violence…” and providing “a framework for how to do the work of ending sexual violence” (Langone). However, the present paper looks at the #MeToo strictly as an ideological springboard that rewires our understanding of cultures and utterances about sexuality in the graphic medium, especially comics.

In a recent interview of Crumb by Nadja Sayej, a culture journalist, published in The Guardian, Sayej refers to Crumb as the “…bad boy of the comics world” who has forsaken the “female form” in his art and conjectures that it may be the result of the #MeToo. Crumb’s reaction to this is interesting to note as it hits hard on the paradox of the situation which is at once human, marked by the codes of morality and ethics on the one hand, and spiritually artistic and liberal on the other. Crumb, now a 75-year-old man reflects: “I don’t even look at women any more…I try not to even think about women any more. It helps that I’m now 75 years old and am no longer a slave to a raging libido.” He adds that things have changed after he has received criticism: “I became more self-conscious and inhibited. … Finally, it became nearly impossible to draw anything that might be offensive to someone out there, and that’s where I’m at today ... So yeah, I don’t draw much anymore … It’s all right. A lot of ink has gone under the bridge. It’s enough.” These words of the underground cartoonist bear both the tone of an unmistakable sadness about the current state of things and a consequent sense of self-imposed recluse. The tone of sadness and the consequent recluse can be understood not simply as a reaction to the MeToo movement as such but towards the corollary conversations and an undercurrent of conservatism it has evoked which hampers free expression. In another of his interview with Christian Monggaard in 2019, Crumb laments the recent rise in extreme ideologies and the stringent need of being always politically correct. He observes: “Now there is a rise in young people…in America…that are becoming very very extreme about sexism and racism and feminism and MeToo.” In the present context the paper shall attempt to delve deep into these words of Crumb as an artist’s reaction to the current events, probably fueled by the ethos of the MeToo, and attempt to re-cognise the effects of censorship, an order for regulating creative content issued by the authority and its effect on the creative urge of an artist. The paper would attempt to formulate the situation as a Creative Paradox, which the author identifies as the dichotomy between human codes of ethics and morality already framed in the society and artistic freedom as experienced and expressed by an individual.

Creative Paradox: Crumb and the Underground

The creative paradox as would be expatiated in the paper is in continuation with age old ideas of censorship that human beings have confronted ever since they knew expression in the form of art and literature. Beginning from Plato’s ban of poets from his republic in ancient Greece to the formation of the Index Librorum Prohibitum, list of forbidden books, an effect of the printing press to the recent issuing of Fatwa on Salman Rushdie for his work, banning and censorship has been a long companion of creativity. The specific sort of ban that the present paper shall discuss in relation to Robert Crumb, is a moral censorship, levied on the underground comix because of their explicitly sexual content. The idea of creative paradox, as formulated by the author refers to the dichotomy between free artistic expression of the artist made as being a part of the society and the authoritarian attempt to regulate it in order to save the same society. Creativity in its true nature can be perceived as an irrepressible force that refutes to abide by any stipulated strictures except of its own. However, the free spiritedness of creativity is oftentimes found to be jeopardized by external forces of society, politics, religion, ethics, to name a few. That said, creativity or artistic expression, nonetheless finds its way out by assuming a resistive stance. The paradox of creativity, as is formulated in the present context, lies in this contradiction between the individual expression and the societal codes. The position of the artist is further problematized from the aspect of perception. The artist is perceived to be a free individual, but s/he is also a part of the societal matrix that operates at large thus the questions of the artist’s ethics and moral responsibility towards it come to play. It is a matrix which has to be both continuously deconstructed and reconstructed for the greater good. In the works of artists such a Crumb we see this sense of responsibility duly assumed by the artist by the means of protest against the reductive codifications imposed by the society. Thus, Paul Krassner rightly observes, “Crumb had merely dived headfirst into the abyss of political incorrectness, serving as a one-person antidote to what he refers to as ‘mass-media-friendly-fascism’” (Beauchamp 24). However, it should be remembered that since the individual and the society are mostly in a position of contradiction, the artist’s intention are often misjudged and misinterpreted by the authority which heightens the paradox further. In the interview with Sayej, Crumb confesses: “I only feel ‘misunderstood’ when people react to my work as if I were advocating the things I drew; the crazy, violent sex images, the racist images … I think they’re not getting it.” Thus, what becomes pronounced is the fact of an artist’s struggle to bring about an effective change in the society.

In the present paper, which is going to discuss the works of Crumb, an Underground Cartoonist, this paradox is further problematized precisely because of two reasons. Firstly, Crumb’s comics grew out of a strong sense of resistance to defy the authority—the Comics Code Authority to be precise, making his comics a means to shatter all taboos and hypocrisies inherent in the society. This was in the 1960s and 70s which even then produced sufficient uproar. In the present scenario informed by the #MeToo, this temperament of free expression is again significantly problematized due to the talks of sexual exploitation that has victimised a lot of men and women. However, ironically enough, while on the one hand, this new sense about expressions of sex, enabled by the #MeToo, has revealed the supressed stories of brutal exploitation, on the other hand it has overshadowed understandings of artistic expression to some extent. This very concern has also been articulated by Priscilla Frank, Art & Culture Reporter, in her very insightful article ‘In the #MeToo Era, Do these Paintings Still Belong in a Museum?’ in 2017. Frank, who seems to suffer from the same dilemma about expressions of sexuality in visual arts, questions the role of museums which are not simply dead archives, but “are living, breathing organisms,” (quoted in Frank) that are supposed to respond and reshape the opinion of the masses. Probing the question of female nudity and the role of the white male artist, she rightly opines that nudity, and the female subject has long been the content of paintings; the problem lies in “the imbalance of power behind many of those paintings, a dynamic that positions woman as the eternal object of beauty and man as the genius creator and authority of it.” From such a point of view, Crumb’s position can be sufficiently problematized as has been done by Underground cartoonists like Trina Robbins. However, the idea that the present paper would attempt to bring home, can be articulated in the words of Ronna Tulgan Ostheimer, director of education at the Clark Museum in Williamstown, Massachusetts, who points out the necessity of including the voices of the “other” and encouraging discussions, rather than eschewing a piece of art from the public view (Frank).

The Comic Code and Censorship

In the mid-1940s, as pointed out by David Hajdu, comics held an iconic cultural value in America as a conspicuous form of entertainment whose sales ranged from eighty million to a hundred million copies every week. Comics outnumbered all other modes of entertainment such as television, radio, and cinema, consolidating its position as a thriving industry that embraced people from all strata of society irrespective of racial, ethnic or gender affiliations (Hajdu). In our present discussion of misogyny in the works of Crumb, it would be interesting to note a paradox that was evident in the Underground Comix industry at large. As opined by Galvan & Misemer, though the Underground comix industry was majorly ruled by “straight white men, such as Robert Crumb and Art Spiegelman, excusing their misogyny, heterosexism, and racism by framing it as a celebration of breaking taboos as comics addressed more adult subjects [.]” there were also quite a number of women artists like Trina Robbins, Lee Marrs, Willy Mendes, Lora Fountain, Aline Kominsky, Sharon Rudahl, Joyce Farmer, and Lyn Chevli who dominated the scene (Arffman 193). Thus, it can be argued that the underground comix industry grew into various socio-culturally aware set of values coming from various sects of the society who were otherwise invisible in other jobs. Such an industry, therefore, exhibited immense potential for registering a significant dissent solely by the virtue of being a social and cultural outcast. Thus, the underground comix scene became an unofficial incubatory ground for the social and political non-conformist, eventually, forming a network of similar sensibilities, though not appropriated by the highbrow elitists, but powerful enough to thrive in the squalor and create a counter rhetoric of the existing ethos.

To understand the underground comix scene not simply as a movement but as a thriving industry is to recognize the fact of achieving a sense of agency on the part of not only the producers of comix but also the consumers—the young readers. Building on the dissenting pulse of the comic books, on the one hand, and its tricky role in parenting young minds, on the other, Hajdu comments:

In the forties...the idea of youth culture…as a vast socioeconomic system comprising modes of behavior and styles of dresses, music, and literature intended primarily to express independence from status quo—had not yet formed; childhood and young adulthood were generally considered states of sub adulthood, phases of training to enter the orthodoxy. Comic books were radical among the books of their day for being written, drawn, priced, and marketed primarily for and directly to kids, as well as asserting a sensibility anathema to grown-ups. (5)

This nurturing of a counter sensibility which is “anathema to the grown-ups”, soon confronted a huge societal resistance formed by the guardians of the society and duly expressed by the newspapers. Being produced in the early postwar years, comics witnessed a great shift in the tone and content which was now deeply influenced by the pulp fiction and film noir (Hajdu). Hajdu rightly points out, comics at that time became “[U]ninhibited, shameless, frequently garish and crude, often shocking” (6) and as a consequence, effected a deep crystallized social disgust among the ‘adults’. Agitations reached its peak when Frederic Wertham, an American psychiatrist published the infamous incendiary tract Seduction of the Innocent: The Influence of Comic Books on Today’s Youth, which pointedly accused comic books causing juvenile delinquency. Dr. Wertham’s book reacted against the graphic illustrations of horror and crime which according him negatively affected the young minds (Sabin). This created sufficient furor in the general mass and as a result, in 1954 the comic book publishers formed together a self-regulatory group by the name of The Comics Magazine Association of America to administer a code of conduct supervised by a review body called ‘The Comics Code Authority’. Comics historian Roger Sabin aptly summarizes the ‘code’. He points out:

This ‘code’ consisted of a list of prohibitions. There were to be no references to sex, no excessive violence, no challenges to authority, and so ... every new title was thereafter submitted for approval. If it passed, it ran with a cover stamp ‘Approved by the Comics Code Authority’; if it failed, it did not get distributed. In Britain, Parliament passed a law, ‘The Children’s and Young Persons Harmful Publications Act’ (1955), which effectively banned the offending comics from entering the country, or from being reprinted. (68)

This boiling issue of censorship rocked the entire comic scene leading to the unemployment of hundreds of comic artists, writers, and editors some of whom were lost in oblivion forever. As Sabin observes, “The Code certainly marked the end of a phase in American comics development.” (68). Thus, we can easily deduce that the Underground Comix was born into the air of a creative paradox that was prevalent at that time and aimed to nullify, subvert and challenge the state imposed moral coding by revolutionizing the genre itself, both in form and content and thereby segregating itself from the Marvels and the DCs. It is from such ideological framework that the present paper would attempt to deal with the questions of misogyny in the works of Robert Crumb.

Entering the Underground

Underground comix, as the name suggests, drastically differed from the ‘upper-ground comix’, promoted by the code. In fact, they were mostly antithetical to the mainstream comics. Comics historian Roger Sabin aptly defines the genre as follows:

The late 1960s saw the emergence of ‘underground comix’, a new wave of humorous, hippie-inspired comic books that were as politically radical as they were artistically innovative…Instead of pandering to a kid’s market, these titles spoke to the counter-culture on its own terms…dealing with subjects like drugs, anti-Vietnam protest, rock music and, above all, sex. (92)

It is worth noting, that the ‘x’ in ‘comix’ is meant to emphasize its X-rated contents. Underground comix was, however, not an overnight phenomenon, but a culmination of various creative forces of the time. Apart from drawing heavily from the countercultural scene, Underground Comix is indebted to the comics tradition of the MAD magazine founded by Harvey Kurtzman in 1954 which according to Sabin, “had liberated comedy in comics”, inspiring many undergrounders (92). There is also the influence of college magazines which focused not only on “localized, campus-satire”, “but also took in more wide-ranging political issues” (92). The entire movement of the Underground Comix became synonymous with one man named Robert Crumb—who both invented and shaped the movement (Sabin 103). Crumb arrived at San Francisco, “the undisputed ‘hippie capital’” (Sabin 94) in 1967 and immediately began publishing in the alternative papers, and in “1968, his first solo comix appeared, Zap…. This was to be the title that started the whole comix ball rolling” (Sabin 94).

Zap immediately reacted to the countercultural pulse that sought an unconditional freedom from every authoritative binding, be it social or political. It is worth noting here the words of Crumb himself whose art was avowedly registering its dissent against every possible stale socio-political and cultural imperative, trying to justify their uninhibited portrayal of sex, as quoted in Sabin. Crumb thus clarifies,

People say “what are underground comix?” and I think the best way to define them is to [talk in terms of] the absolute freedom involved. I think that’s real important. People forget that that was what it was all about. That was why we did it. We didn’t have anybody standing over us saying “No, you can’t draw this” or “You can’t show that.” We could do whatever we wanted. (95)

The intention of the artist as expressed in the quoted words finds fruition in the words of another follower of Crumb and a cartoonist herself, Lynda Barry. She recalls, “What R. Crumb gave me, was this feeling that you could draw anything.” (Chute 95). To Crumb, this freedom was sought through the explicit sexual content which operated as a mode of resistance in his hands. From our present understanding we can sufficiently argue that this spirit of absolute freedom as desired, expressed, and to some extent achieved by the underground cartoonists is antithetical to the laws of the society which functions on the principle of social contract to surrender to the hierarchies in the power structure, heavily coded by morality. Thus, contemporaries like Trina Robbins, an underground cartoonist herself and one of the pioneers of Wimmen’s Comix strongly criticized Crumb for what she identified as misogyny in his panels. In her essay “Underground Cartoonists: Wimmen’s Comix, Wet Satin” she observes:

It’s weird to me how willing people are to overlook the hideous darkness in Crumb’s work ... I guess the worst of it to me is that Crumb became a cultural hero that his comics told everybody else that it was okay to draw this heavily misogynistic stuff. The phenomenon of the underground comix of the seventies, so full of hatred toward women, rape, degradation, murder, and torture, I really believe can be attributed to Crumb having made this kind of work stylish. (41-42)

Robbins’s words were gravitating towards denouncing the apparent male chauvinism in the works of Crumb, which was again iterated by Ian Blechschmidt, who makes a “gender-informed rhetorical analysis of a selection of underground comix” and opines:

Far from freeing readers from the weight of history and ideology as many scholars of underground comix (and respondents to this study) might claim, then, underground comix rather reinscribe the age-old normative myth of the self-generated, self-sufficient (male) agent, sometimes called “The American Adam.” This reinterpretation of underground comix and their importance to the USA’s cultural history has important implications for how we understand their legacy and their revolutionary potential. (3)

Blechschmidt’s idea of the American Adam has also been echoed by Galvan and Misemer as they identified Crumb and his followers as a group of quasi radical cartoonists who “merely perpetuate an exaggerated version of the heterosexism of mainstream media, such as television and film” (1). These criticisms generally seem to throw into relief the artist’s intension behind his art. In an interview with Gary Groth for the Comics Journal Library Crumb strongly clarifies his position as an artist by harping on the creative urge which is oftentimes in contradiction with the society at large. Crumb observes:

I wouldn’t judge or condemn work purely because it’s misogynistic or racist or anything else; I would judge and condemn it on whether it was interesting or boring, whether it was honest and truthful and real, or whether it was just somebody attempting to pander to some market they think is out there, or trying to imitate something they’ve seen — someone trying to be successful, or whatever — instead of saying what’s really on their minds, dredging up what’s really in there. If it’s really in there, it ought to come out on paper. Better that it comes out on paper than to repress it and let it squeeze out in some rageful, angry act in the world. I never believed, and I’ve said this thousands of times, that drawing something in a comic book is very dangerous or harmful as far as influencing people’s behavior. (No pagination)

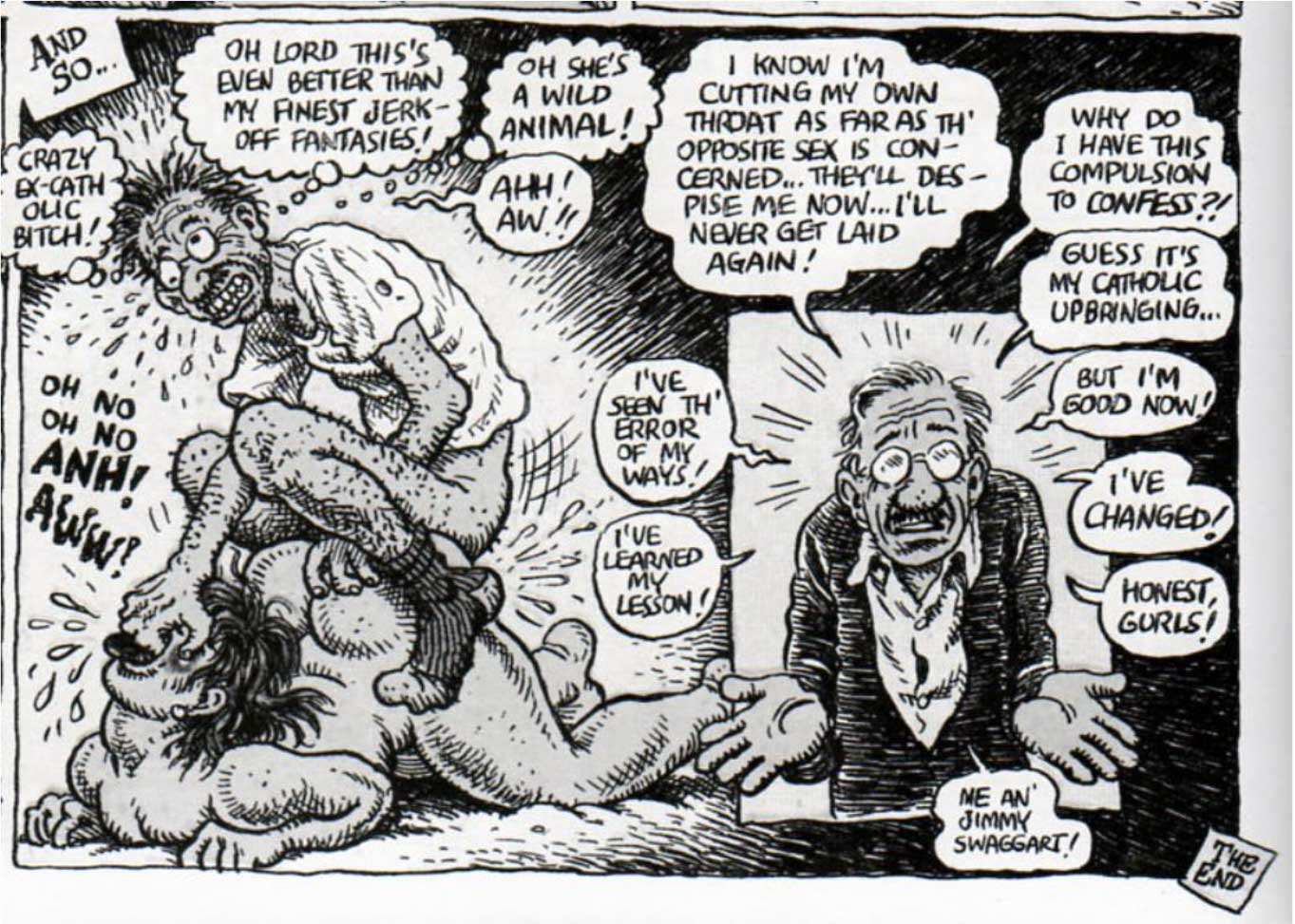

These words of Crumb speak sufficiently of his artistic credo that seeks to build upon the ideals of truth and absolute self-expression which is uninhibited and fearless. In the words of Crumb it is his “compulsion to reveal” the truth as opposed to the “pretty things” that most people would like to see. This compulsion constitutes his creative impulse which intensifies the paradox inherent in the situation. Crumb who believes in the honesty of the artist (Groth) himself talks about his ‘compulsion’ in “Memories are Made of This.” The story anthologized in My Troubles with Women, tells the story of Crumb visiting a woman on a rainy winter night of 1976, evidently with the intention of having sex. We see Crumb travelling by bus in the midst of that rain to reach the house of the woman. Initially it seems like a casual conversation but soon the situation turns as we see that Crumb makes his move on the woman who by now is in the stupor of intoxication. The story ends with the two having a violent sexual intercourse.

Fig. 1.

For the readers and critics this is where Crumb becomes difficult to read as our moral coding instigates us to be judgmental towards the artist and his art. The ambiguity is further intensified in the very last panel of the story where on the one hand we see the couple engaged in a sexual activity and on the other hand in an inset Crumb confessing his guilt and his “compulsion to confess” his stupidity in matters of women and sex. In the words of Hillary Chute “Crumb’s work – especially when occupied with race and sexuality – makes the line between satire and embodiment a difficult or impossible one”. This problem is evidently due to the medium it engages in, that is comics. For instance, in “Memories are Made of This”, Crumb reminisces his older days when he “SPENT ALOT OF MY TIME CHASSING AFTER “PUSSY” (13). Now if he has to put it in comics then he will have to ‘show’ (McCloud) things that had happened which means the images describing his older days of chasing women will be sexually vivid and misogynistic to some for valid reasons. But this embodiment of the events narrated in the story has to be read in conjunction with the words accompanying it. Comics is a composite art form of images and texts where the texts function to ‘tell’ (ibid.) things alongside the images. Thus, the last panel of the story will bear a different significance if read from this aspect. The reader would realize the importance of the words said along the images:

I KNOW I’M CUTTING MY OWN THROAT AS FAR AS THE OPPOSITE SEX IS CONCERNED…THEY’LL DESPISE ME NOW…I’LL NEVER GET LAID AGAIN!...WHY DO I HAVE THIS COMPULSION TO CONFESS?!...GUESS IT’S MY CATHOLIC UPBRINGING…BUT I’M GOOD NOW…I’VE CHANGED…HONEST GURLS! (16)

The tone of satire as pointed by Chute is unmistakable but what is significantly evident is the fearless honesty of the artist that is posing a difficult question to the readers and the society as well. Thus, Crumb’s artistic credo is not bluntly sexual but a conscious attempt to destabilize the sanitized idea about sexuality through his art.

The Sex Talk

All these conversations about sex or its graphic depiction to be precise did not begin with Crumb, though it was he who consolidated it through the underground comix movement. Two very significant cultural artifacts that existed before Crumb’s uninhibited graphic expressions about sex, needs mention in this context. These were the Tijuana Bibles and the Playboy magazine, two very popular publications that directly dealt with sexual content (Chute 104). Anonymously published in the 1930s and 40s by a group of unknown underground artists, the Tijuana Bibles were “under-the-counter pornographic comics pamphlets” (Chute 104). These were so popular among young male readers that Adelman wrote in the ‘Acknowledgment’ section of his book, Tijuana Bibles: Art and Wit in America’s Forbidden Funnies (1997), it was their “first peek into the forbidden world of erotic intimacy”. Tijuana Bibles, in spite of being out-rightly pornographic comics holds a very significant crux in in terms of development of sexual expression in the graphic medium. It can be argued that, though the license to talk about sex was given currency by the Bibles, but as Art Spiegelman, another celebrated cartoonist, notes,

I know that some of my slightly older and wiser underground-comix cohorts like Robert Crumb and S. Clay Wilson had been exposed to these booklets in childhood, but for most of them it wasn’t a watershed moment in their development as artists—more an outhouse moment in their development as adolescents. The Tijuana Bibles weren’t a direct inspiration for most of us; they were a precondition. That is, the comics that galvanized my generation—the early Mad, the horror and science- fiction comics of the fifties—were mostly done by the guys who had been in their turn warped by those little books. (Adelman 5)

These words of Spiegelman, brings us to another critical juncture, that though the sexual fervor was undoubtedly consolidated by the Bibles, their intention was very different from those of the later artists. In the words of Chute they manifested a strong parodic vein against the celebrity cultures of the time (104). Thus, if we have to, at all place Crumb in this scenario we have to address the equivocality of the situation. Crumb’s works were influenced by the Bibles in the sense that, they exhibited an unmistakable tone of satire against the dominant cultures of the time, but hugely differed in their intentions of such depiction and sex in the hands of Crumb was not just a superficial means to assure the commercial viability of his comics, unlike Playboy, but a potent weapon to unravel the long history of a capitalistic repression of his nation and its peoples. It is interesting to note that in 1953, just a year before the formulation the Comic Code, one of the most popular men’s magazines, Playboy came into existence. The magazine, appearing in the post-war period, soon became a global brand and the bunny logo of the magazine was only second to Coca-Cola in its popularity (see Jancovich). It presented a sanitized, cleaned up sexuality that was easy, quickly satiable and guilt free. Hugh Hefner, the founder of the magazine, in an interview with Oriana Fallaci for the LOOK magazine, explains their bunny logo:

The rabbit, the bunny, in America has a sexual meaning; and I chose it because it’s a fresh animal, shy, vivacious, jumping—sexy. First it smells you then it escapes, then it comes back, and you feel like caressing it, playing with it. A girl resembles a bunny. Joyful, joking ... She is never sophisticated, a girl you cannot really have. She is young, healthy, simple girl—the girl next door … The Playboy girl has no lace, no underwear, she is naked, well washed with soap and water, and she is happy. (118)

Reacting to such reductive and hedonistic attitudes, Crumb points out that “Playboy really represented prosperous American hedonism” (Groth 27). Describing the Playboy scene, Crumb further argues:

A classic post-war hedonist. That’s what the Playboy thing was all about: “OK, guys, we won the war, it’s our world, let’s live it up. Throw off all hypocrisy, if you’re a smart, liberal, intelligent guy.” (Groth 27)

Thus, we can now sufficiently argue that Crumb, creating at the crosscurrents of the counterculture that rode on the spirit of freedom, on the one hand and a sense of spiritual bankruptcy marked by unbridled “self-indulgence and consumption” (Pustz 137) on the other, was determined and fearless enough to flesh out the despondency of the time as well as his own. Unlike other forms, comics has always been a very private and self-indulging mode of expression (Chute 129) and Crumb’s graphic utterances were nothing but expressions of his own pungent anger towards the time that he was living, and sexuality or sexual outburst were a part of it.

This becomes evident in the prologue of Zap #01 titled, DEFINITELY A CASE OF DERANGEMNT! (Fig. 2), which

Fig. 2.

is an unhinged articulation of Crumb’s own lunatic ravings and his probable sexual aberrations directed towards his wife as manifested through the precarious figure of his naked wife cowering in the corner of the room. The entire panel posits a strong sense of destabilising madness which has evidently exerted an overwhelming influence on Crumb too, as projected through his dishevelled countenance. We see him yelling out disconnected words of vain frustration to no one in particular but perhaps to the society at large. We realise that the panel darts out of the liminality between reason and madness, civilised sobriety and sexual aggression. The image of the naked wife, petrified, probably due to her immediate disturbing experiences is aesthetically clubbed with other unsettling factors within the panel such as the disjointed words we see in the speech bubbles. The significance of the medium of comics, unlike photograph is that the former deals in both words and images as opposed to the former. Thus, the apparent misogyny recedes to awaken us to the entirety of the situation where sexual expressions become a mode of reaction. However, this is in no intention to dilute and justify the case of misogyny but to read the vulnerability of the individual artist at the hands of the forces at large.

Beth Bailey, in her seminal essay, ‘Sex as a Weapon: Underground Comix and the Paradox of Liberation’, anthologised in Imagine Nation: The American Counterculture of The 1960s & ’70s, aptly sums up the position of sex in the Countercultural scene. Though the paper refers to this essay, providing an insight into the interface between the countercultural movement and the overt use of sexual images by the underground cartoonists, it would beg to differ from its final conclusion that conforms to the allegations of misogyny and matter-of-fact nudity in the underground art. Hence the author’s reference to the essay is strictly limited to the insightful summing up of the contemporary socio-political and cultural scene that confronted the crosscurrents of the time. Bailey argues:

Sex & drugs & rock and roll: the phrase has served as both mantra and epitaph for the incoherent phenomenon of “the counterculture” in America. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, it offered a symbolic center for the centripetal force of the movement/ conspiracy/ revolution/ lifestyle that sought to counter what its members saw as America’s war culture, the plastic materialism of American suburban successes, and the persistence of a culture of scarcity (seen in the Protestant work ethic and the repression of sexuality) in the midst of abundance. (305)

Thus, we can easily perceive that sex became a potent weapon in the hands of the practitioners of the counterculture to destabilize the authority, which was singularly vying for materialistic flourish, indifferent of the development of the larger mass. Crumb too, who spearheaded the underground comix movement, capitalised his images of harsh and unabashed sexuality to reinvigorate not only the drug induced inert youth but also to refurbish the language of comics itself, making it a powerful pocket of resistance. Bailey in her essay specifies the very reasons behind using candid images of sex by the underground papers. She points out:

Portrayals of sex in…underground papers had two major purposes. Frequently, contributors and editors attempted to use graphic or otherwise “offensive” representations of sex to confront—and offend—mainstream society. The underground press also used sex as a symbol of freedom and liberation, seeking graphics and language and attitudes that clearly transcended the strictures of a repressive society. (308)

Crumb’s images too spoke of such absolute freedom and strongly marked a note of vigorous subversion in the children’s world of comics by transforming it to ‘comix’. The comics with an ‘X’ no longer remained a bloodless expression of fantastical ideas but sought to communicate to the adult readers making it a ground of expressing the very primal primordial trepidations of the grown-ups.

Fig. 3.

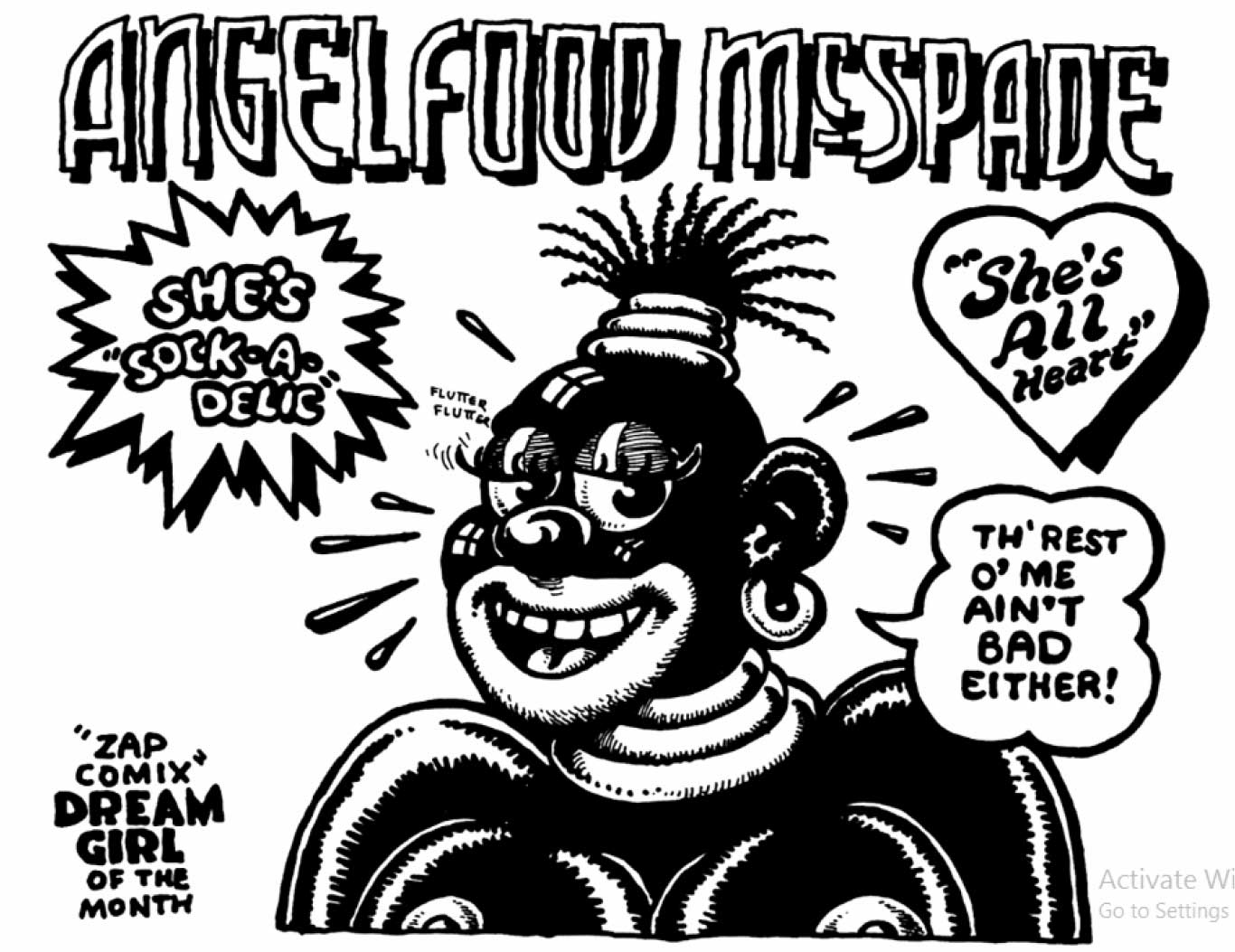

One of the characters that sufficiently draws criticism on the grounds of misogyny and racism is Angelfood. The character of Angelfoood derives its aesthetic potential not only due to its massive subversion of the commercialised concept of beauty reiterated by the mainstream magazines but also for lampooning the narrow racial instincts of the whites that not only dehumanises the non-white people but also subsumes all their deeper desires upon them. Alan Moore, in his essay on Crumb, anthologised in The Life and Times of R. Crumb asserts his love for AngelfoodMcSpade, highlighting her stark contrast from the “commercial gloss and the self-conscious poutings of the ex-stenographers staked out across the center spread” (73). He observes:

Angelfood was different. She was wearing, in addition to her grass skirt, a big pleased-with-herself smile rather than the slightly concussed “just raped” look that her cover girl contemporaries were starting to adopt. It was my first taste of the sexual openness of the psychedelic movement…. Sexuality aside, this drawing was subversive. (74)

Expatiating further on the subversive portrayal of Angelfood, Moore observes:

…it was subversive in the way it commented upon race. Many cartoonists since Crumb have referred back, ironically, to the stereotyped image of black people that dominated the cartoons of the past. But this was the first time I’d seen a cartoon depiction of the Negro so exaggerated that it called attention to the racialism inherent in all such depictions. (74)

True to the words of Moore, we see Crumb’s acute aversion toward racialism embedded not only in the images contrasting the timid black woman with the city-bred group of white explorers which are not only ironic reiteration of early racist graphic portrayals, but also in the entire narratorial schema, it apparently posits a crude misogynistic attitude. Almost resembling a TV commercial, showcasing different aspects of a product, the narrative dissolves Angelfood’s essential identity as a human being through an objective portrayal of different parts of her body, evoking a sense of unrestrained sexuality. She is labelled as the “ZAP COMIX DREAM GIRL OF THE MONTH” which becomes a direct parody of the ‘Playmate of the Month’ of the Playboy magazine. Thus, Crumb’s intention to counter the mainstream media’s pre-occupations with sex and women becomes candid, as we see the over exaggerated figure of Angelfood smiling invitingly with shy fluttering eye lids at the readers. However, this critique of mainstream media by Crumb, attracts a very different problem which has been articulated by feminist critic Kimberlé Crenshaw. The exaggerated portrayal of Angelfood becomes a telling expression of what Crenshaw has been trying to advocate—the idea of ‘intersectionality’ between race and gender. Though Angelfood becomes emblematic of the arguments about sexual and racial discriminations that Crenshaw had clearly pointed out, the problem with such representation is:

The claim that a representation is meant simply as a joke may be true, but the joke functions as humor within a specific social context in which it frequently reinforces patterns of social power. Though racial humor may sometimes be intended to ridicule racism, the close relationship between the stereotypes and the prevailing images of marginalized people complicates this strategy. And certainly, the humorist's positioning vis-a-vis a targeted group colors how the group interprets a potentially derisive stereotype or gesture (1294)

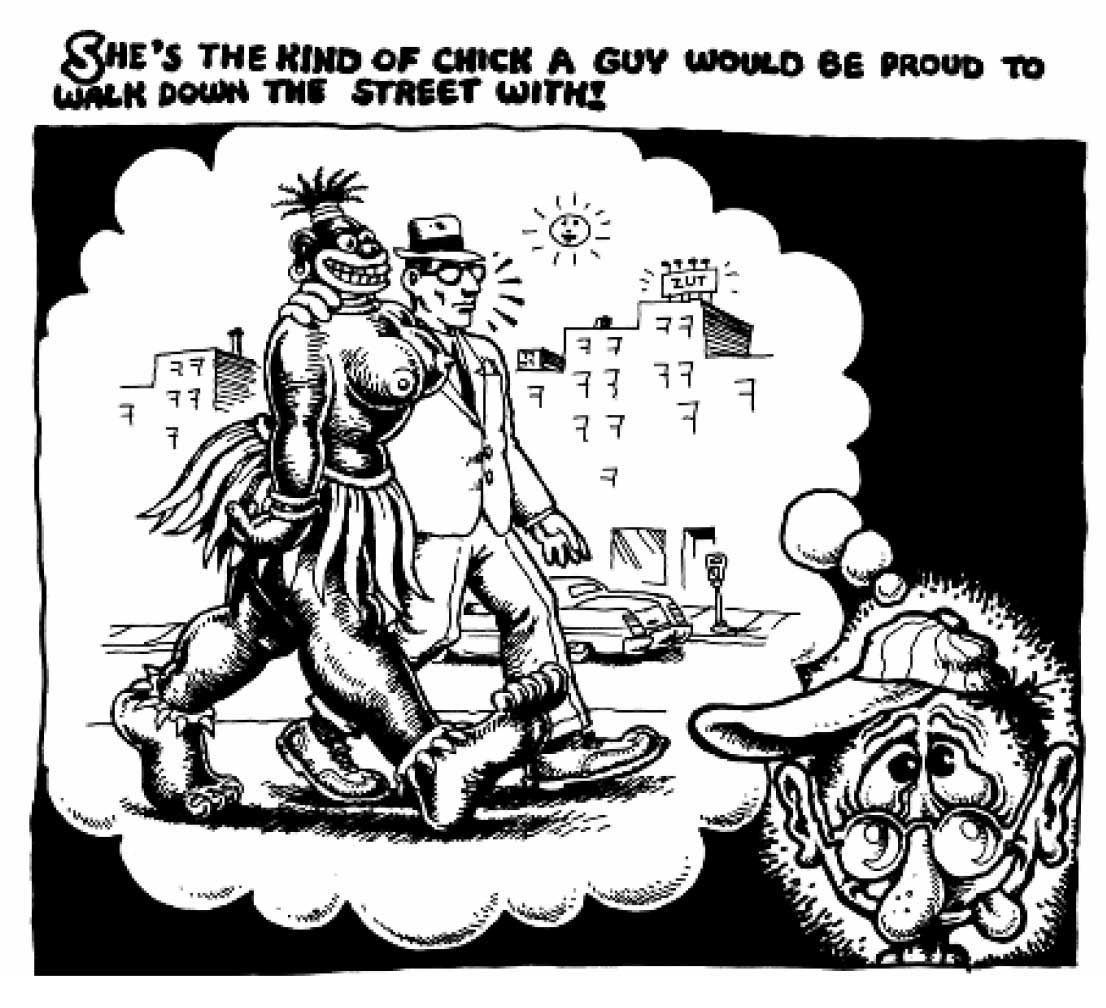

Thus, it becomes but natural for critics like Trina Robbins who in a different context makes a caustic attack towards the “hideous” portrayal of “AngelfoodMcSpade being screwed while her head is submerged in a toilet bowl” which is a reference to “FINGERLICKIN’ GOOD” in Despair magazine. Here also, as has been argued previously, Robbins overlooks the fact that comics is not simply about the showing of images, but also about the telling of the words and the narrative of comics takes shape from a happy wedlock of the two. It will be an injustice therefore to decontextualize the images from the written words as both together constitute the text. Thus, while the images of FINGERLICKIN GOOD forcefully bring out the raw desires of the white men, the words unmistakably harp on the abominable racist attitudes of those civilised men. We see that a group of three white men, sophisticated and civilised, almost forcefully intrude into the peaceful haunt of Angelfood when she was completely alone. The group of white men, motivated by the great white man’s burden to educate, uplift and enlighten the natives of Africa, assures Angelfood that they have come to assist her “IN BECOMING A PRODUCTIVE MEMBER OF SOCIETY!” The bafflement of Angelfood at their words is unmistakable whose pristine innocence is steadily and methodically interrupted by the cunning words of the three men. However, the cruelty of the whites spills out of the panels as we see Angelfood’s posterior bent down into the commode in order to lick them clean in lieu of some money which the men have promised her and then suddenly the three men burst into the room and quite sickeningly shit on her. The crude abhorrence of Crumb is expressed from the very interdependency of the words and images assisting in the building of the text. In the present context too, Crumb through his portrayal of Angelfood almost gives a telling shape to the primordial desires of men that always want to consume the female body. A deeper probing, especially into the intention of the artist behind such apparent misogynist portrayals, as pointed by Crumb himself, will reveal the fact, that the images are instrumental in unravelling the complex knots of desire and derision unconsciously harboured by the civilised whites towards the people of colour. While on the one hand we see that Angelfood shapes the ultimate desire of men in being an attractive denizen of their dreams (Fig. 4),

Fig. 4.

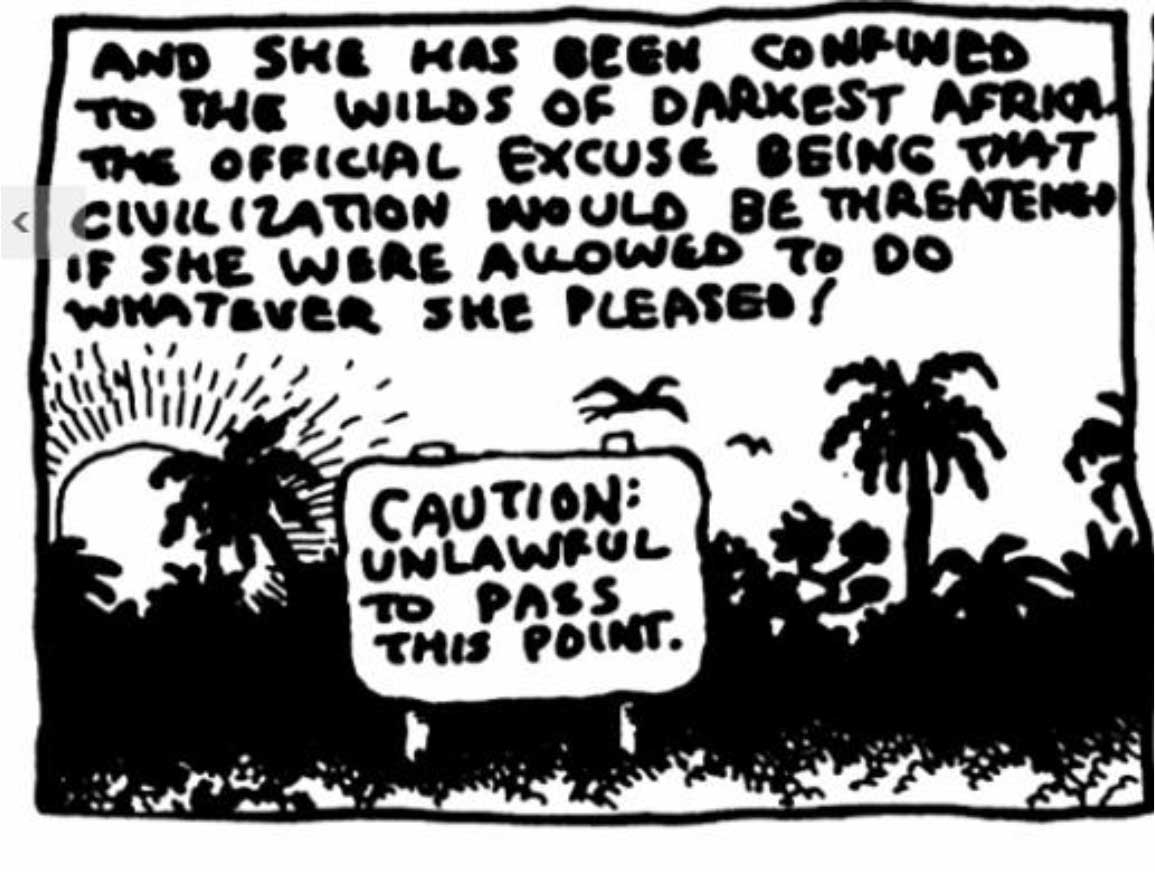

the government, on the other hand, seeking absolute status quo by suppressing the strong sexual desires lurking underneath the civilised visages, puts up a board restricting passage into the dark jungles of Africa (Fig. 5)

Fig. 5.

What becomes interesting is that the story not only projects the marginalisation of Angelfood who is doubly marginalised for being a woman and black, but also the precarious state of the not so successful city people as presented in the figure of the explorer, who is prohibited by the police in his quest for Angelfood. Especially, the panel projecting the dream of the hapless explorer to acquire Angelfood, makes a simultaneous commentary on the primacy of a social stability which may help earn the possibility of realising one’s dreams. Even to possess Angelfood, one requires to have an economic and social viability as suggested in the figure of the rich and sophisticated gentleman. Thus, we can realise that underneath the shocking representations of sex and sexuality, Crumb weaves another tale of repression, singularly to destabilise any authoritative structure that strives to thrive upon the sabotaged desires of the weak.

Thus, the allegations of misogyny and racism brought against the works of Crumb can be sufficiently swept away as we discover the intention behind it. In the words of Ray Zone Crumb’s “purpose is satire” which “demolishes not only the puny pretentions of the individual but also those of time, history, and society.” He further observes:

The satire of Crumb demolishes all that stands before it. It is an immense affront to, and simultaneous sweeping away of, the lies of history and the hypocrisy of culture in which are woven the insidious and blood-red strands of sex, religion, identity, nationalism, gender, and class. This cleansing and devastating act of washing away the accumulated lies of civilization is the healthiest act of preparation to build a new, millennial society founded upon the values of humanity rather technology, spirit rather than politics. (The Life and Times of R. Crumb, 179-180)

Probably now we can sufficiently answer the question that was raised at the very outset of the paper—why did Crumb chose to be sexually explicit? Bandon Nelson who also enquired the purpose of such depiction, identifies an “apolitical phantasmagoria” in the works of Crumb and observes that they are a product of “experiences of repression and oppression” which “can be responded to with fetish and the intentional oversaturation of previously normalized racist and misogynist imagery.” He further observes:

By couching obscene depictions of violence and sexuality in the style of American comics produced earlier in the twentieth century, and by reproducing offensive racial and sexual caricatures absent of any obvious attempt to condemn or interrogate them, the works of R. Crumb represent an aesthetic of perpetual and apolitical obscenity that favours the collision of discordant styles and themes as its method for ultimately achieving ideological nullification and correspondingly unfettered indulgence and gratification. (140)

Though Nelson rightly points out the experiences of socio-political repression as the primary cause behind the artistic output of Crumb, but it somehow seems to fail in capturing ideological implications in the works of Crumb. Far from being an “apolitical phantasmagoria” Crumb’s art is soaked in the politics of destabilizing the authority and every possible social norm as is evident from our analysis so far. It is the idea of artistic independence that Crumb upholds that refuses to be coded by any authority thereby nullifying the creative paradox.

Conclusion

The idea of creative paradox that amply identifies the underground comix’s attempts to question authorities like the Comic Code, thus, brings us to the awareness that extreme ideologies can be detrimental to anything that is outside its purview, even sometimes to its own cause. However, it is by no means to underplay the positive impact of the #MeToo, but a call to be sensitive enough to artistic expression and create an atmosphere of freedom which art and artists, both require. Thus, artists like Crumb need more space in our daily discourses about the prevailing cultures of sexuality, so that as readers, and as thinking individuals we can cut short any restrictive ideology that may threaten our free thinking.

Works Cited

Adelman, Bob. Tijuana Bibles: Art and Wit in America’s Forbidden Funnies, 1930s-1950s. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004. Print.

Arffman, Paivi. “Comics from the Underground: Publishing Revolutionary Comic Books in the 1960 and Early 1970s.” The Journal of Popular Culture 52.1 (2019): 169-198. Web.

Bailey, Beth. “Sex as a Weapon: Underground Comix and the Paradox of Liberation.” Imagine Nation: The American Counterculture of the 1960s & ‘70s. Ed. Peter Braunstein and Michael William Doyle. New York: Routledge, 2002. 305-324. Print.

Blechschmidt, Ian. Reading Underground Comix: Masculinity, Authenticity, and Individuality. 2016. Northwestern University, PhD Dissertation. Web.

Chute, Hillary. Why Comics? From Underground to Everywhere. New York: Harper, 2017. Print.

Crenshaw, Kimberlé. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color.” Stanford Law Review 43.6 (1991): 1241- 1299. Print.

Crumb, Robert. “ANGEL FOOD MCSPADE.” Zap Comix No. 2. San Francisco: Apex Novelties, 1968. N. pag. Print.

Crumb, Robert. “DEFINITELY A CASE OF DERANGEMENT.” Zap Comix No. 1. San Francisco: Apex Novelties, 1968. N. pag. Print.

Crumb, Robert. “Memories are Made of This.” My Troubles with Women. San Francisco: Last Gasp, 1989. 12-15. Print.

Crumb, Robert. “Robert Crumb Interview: A Compulsion to Reveal.” YouTube, Dec 23, 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_2ZWrWmypA0 . Web. Accessed on Nov 11, 2020.

Crumb, Robert. Interview by Gary Groth. The Comics Journal Library. Ed. Milo George. Vol. 3. Seattle. Mar. 2004. Print.

Crumb, Robert. Interview with Gary Groth. Comics Journal Library. Nov 19, 2014, http://www.tcj.com/zap-an-interview-with-robert-crumb/ . Web. Accessed on Nov 11, 2020.

Crumb, Robert. Interview with Nadja Sayej. “Robert Crumb: I am no longer a slave to a raging libido.” The Guardian. Mar 7, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/mar/07/robert-crumb-i-am-no-longer-a-slave-to-a-raging-libido . Web. Accessed on Nov 11, 2020.

Frank, Priscilla. “In The #MeToo Era, Do These Paintings Still Belong In A Museum?” Huffpost, 14 Dec 2017, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/museums-me-too-sexual-harassment-art_n_5a2ae382e4b0a290f0507176 . Web. Accessed on Jun 4, 2021.

Galvan, Margaret: Misemer, Leah. “Introduction: The Counterpublics of Underground Comics.” Inks: The Journal of the Comics Studies Society 3.1 (2019): 1-5. Web.

Hajdu, David. The Ten-Cent Plague: The Great Comic-Book Scare and How it Changed America. New York: Picador, 2008. Print.

Hefner, Hugh. “I am in the center of the world.” Interview by Oriana Fallaci. The Egotists: Sixteen Surprising Interviews, Chicago: H. Regnery Company, 1963. 113- 124. Print.

Krassner, Paul. “Writer: The Realist, Rolling Stone, The Village Voice, Playboy.” The Life and Times of R. Crumb: Comments from Contemporaries. Ed. Monte Beauchamp. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 1998. 23- 24. Print.

Langone, Alix. “#MeToo and Time's Up Founders Explain the Difference Between the 2 Movements — And How They're Alike.” Time, 8 Mar. 2018, https://time.com/5189945/whats-the-difference-between-the-metoo-and-times-up-movements/ . Web. Accessed on June 4, 2021.

Mark, Jancovich. "Placing Sex: Sexuality, Taste and Middlebrow Culture in the Reception of Playboy Magazine." Intensities: A Journal of Cult Media, 2001: 1-14. Web.

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. New York: William Morrow, 1993. Print.

Moore, Alan. “Writer: Watchmen, From Hell, Swamp Things.” The Life and Times of R. Crumb: Comments from Contemporaries. Ed. Monte Beauchamp. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 1998. 71- 82. Print.

Nelson, Brandon. “‘Sick humor which serves no purpose’: Whileman, Angelfood and the Aesthetics of Obscenity in the Comix of R. Crumb.” Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics 8.2 (2016): 139-155. Web.

Pustz, Matthew. “Paralysis and Stagnation and Drift: America’s Malaise as Demonstrated in Comic Books of the 1970s.” Comic Books and American Cultural History: An Anthology. Ed. Matthew J. Pustz. New York: Continuum Publishing Corporation, 2012. 136- 151. Print.

Robbins, Trina. “Underground Cartoonist: Wimmen’s Comix, Wet Satin.” The Life and Times of R. Crumb: Comments from Contemporaries. Ed. Monte Beauchamp. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 1998. 39- 42. Print.

Sabin, Roger. Comics, Comix, & Graphic Novels. London: Phaidon Press, 2014. Print.

Wertham, Fredrick. Seduction of the Innocent: The influence of comic books on today’s youth. New York: Rinehart & Company, 1954. Print.

Zone, Ray. “Publisher/ Writer: The 3-D Zone.” The Life and Times of R. Crumb: Comments from Contemporaries. Ed. Monte Beauchamp. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 1998. 179- 180. Print.

Purba Chakraborty

Assistant Professor of English, PKM Mahavidyalaya, University of North Bengal

PhD scholar, Department of HSS, IIT Roorkee

© Purba Chakraborty, 2021