Nabokov, Cinemathomme

Sigi Jöttkandt

"Set fire to the library of poetics" ––Derrida, ‘Che cos'è la poesia?’

Veeness and Adaness

Vladimir Nabokov begins Ada or Ardor with a botched citation from Tolstoy. If, for the great Russian realist, all happy families are more or less the same, in Nabokov's revision, it is a family's happiness which is singular: "'All happy families are more or less dissimilar; all unhappy ones are more or less alike' says a great Russian writer" (Nabokov 1996b, 7).[1] By opening with Tolstoy, Nabokov signals a certain precedent for his 1969 novel. Its model will be a sprawling 19th-century realist novel detailing a century-long illicit love affair between the half-siblings Van and Ada Veen. Nabokov's gambit is that Ada's lovers will rank with some of the greatest lovers in literary history, including Princess Anna Arkadyevna Karenina and Count Alexei Kirillovich Vronsky, who, as templates for forbidden love, quietly mark themselves in the initials of Ada and Van. Yet beyond its topos of the Russian family estate ––– borrowed seemingly wholesale both for Ada and for Nabokov's gold-flecked memoir, Speak, Memory–– the Tolstoyan intertext is just as important for Nabokov for the formal innovation he assigns to the author of Anna Karenin. This is the stream of consciousness technique, more usually attributed to the great modernists, James Joyce, Virginia Woolf and Marcel Proust. But in his Lectures on Russian Literature, Nabokov demolishes this canard, writing that "The Stream of Consciousness or Interior Monologue is a method of expression which was invented by Tolstoy, a Russian, long before James Joyce."[2] This is how Nabokov characterizes the technique:

It is a kind of record of a character's mind running on and on, switching from one image or idea to another without any comment or explanation on the part of the author. In Tolstoy the device is still in its rudimentary form, with the author giving some assistance to the reader but in James Joyce the thing will be carried to an extreme stage of objective record.

(Nabokov 1981, 183)

The stream of consciousness technique makes its appearance as one among a number of Nabokov's favorite "hates" as these have been itemized in a hand-written list and stored in the archives of the New York Public Library. In this list, whose contents (as Nabokov also notes) were repurposed in Ada for Van Veen's own scribbled musings, a number of stylistic conceits take their place alongside Nabokov's trumpeted dislike of background music, glib phrases, clubs, fraternities, circuses, concise dictionaries, the wrong pocket and everything connected with the post. Together with "abstract" daubs, "symbolic bleak little plays," "junk sculpture" and "avant-garde" verse, the method of identifying stream of consciousness by "italicized passages in novels which are meant to represent the protagonist's cloudbursts of thought" (Nabokov 1964, n.p.) comes in for especial censure.

We will revisit the extent to which Nabokov himself deploys this typographical conceit in Ada which, among many other things, offers an extended meditation on (and parody of) modernist aesthetics, in particular that of James Joyce. But for now, let us note that what Nabokov is objecting to as a bad novelist's typesetting cheat points to a fundamental problem of language, namely, its intrinsic dual ability to convey both the "idea signified" and the idea of language's "role as representation," as Michel Foucault explains. In The Order of Things, Foucault marks the shift to what he calls the Classical episteme in terms of this binarism (Foucault 1994). For Foucault, the 17th century emerges as the period in Western thought when representation becomes increasingly split along two lines: first, language as an instrument for conveying the marks of identity and difference produced through reason's acts of discrimination, and second, what he refers to as "that unreacting similitude that lies beneath thought and furnishes the infinite raw material for divisions and distributions" (Foucault 1994, 57). But this formulation also masks a changed complexity in the possibility of obtaining "truth." Precisely to the extent that language becomes "arbitrary," that is, removed from any "natural" relation that presents as the holdover of a more primitive text written by God, it also begins to make a new claim about its authority. Foucault explains,

The relation of the sign to the signified now resides in a space in which there is no longer any intermediary figure to connect them: what connects them is a bond established, inside knowledge, between the idea of one thing and the idea of another.

(Foucault 1994, 62)

Because of this shift, signs in effect become Janus-faced, pointing both to the idea signified and to its own status as sign. Each sign is thus a "duplicated representation," a sign that doubles over itself.

The fantasy of realist fiction is that it can overcome the sign's inherent duplicity. The pretense of the realist universe is that language offers a window through which one can reach and practically touch the characters whose lives are sketched with such vividness. This near-transparency of literary style is in fact one of the things Nabokov claims to value the most in Tolstoy. He notes Tolstoy's courteous attention to the tiniest details of the Oblonsky and Karenin families' lives––- the "little spike of hoar frost" that falls upon Kitty's muff; the handkerchief that falls out of her muff as she shakes hands with Lyovin; the earrings which she asks her mother to remove during her agonies of childbirth, etc. Marshaling the figure of a perpetual motion machine that generates its own energy sources, Nabokov comments "Tolstoy keeps a keen eye on his characters. He makes them speak and move - but their speech and motion produce their own reaction in the world he has made for them. Is that clear? It is." (Nabokov 1981, 161). The effect, he remarks, is that Tolstoy's readers, "elderly Russians at their evening tea" find themselves talking of Tolstoy's characters "as of people who really exist, people to whom their friends may be likened, people they see as distinctly as if they had danced with Kitty and Anna or Natasha at that ball or dined with Oblonski at his favorite restaurant, as we shall soon be dining with him" (Nabokov 1981, 142).

But this illusion must be kept under tight control. Potential wanderings of the sign are prevented by means of direct speech markers that fence in the flows of consciousness within the realist universe, enabling the reader to parse the order of events inside narrative time. This extends to memories and dreams as well as to characters' explicitly conscious states. "Yes, yes, how was it now? [Stepan Oblonski] thought, recalling his dream.

"Now, how was it? To be sure! Alabin was giving a dinner at Darmstadt; no, not Darmstadt, but something American. Yes, but then, Darmstadt was in America. Yes, Alabin was giving a dinner on glass tables, and the tables sang, Il mio tesoro—not Il mio tesoro though, but something better, and there were some sort of little decanters on the table, and they were women, too," he remembered. (trans. Nabokov, cited in Nabokov 1981, 150)

Despite his faulty memory and the dream's own distortions and illogic, Oblonski's - and the reader's - perspectives remain temporally orientable by means of Tolstoy's use of direct speech. With the modernist break, however, the corralling duties of conventional typography become outsourced to the more permeable membranes of the stream of consciousness and its close cousins, interior monologue and free indirect discourse. And with this permeability, the time of consciousness becomes plastic. Nabokov describes the stream of consciousness technique as representing the mind "in its natural flow, now running across personal emotions and recollections and now going underground and now as a concealed spring appearing from underground and reflecting various items of the outer world" (Nabokov 1981, 183). A famous section from Tolstoy from Anna's "last day" provides Nabokov with his example:

Office and warehouse. Dentist. Yes, I'll tell Dolly all about it. She does not like Vronski. I shall be ashamed but I'll tell her. She likes me. I'll follow her advice. I won't give in to him. Won't let him teach me. Filipov's bun shop. [...] Dressmaker. Man bowing. He's Ann Ushka's husband. Our parasites. [Vronski had said that.] Our? Why our? [We have nothing in common now.] What's so awful is that one can't tear up the past...What are those two girls smiling about? Love, most likely. They don't know how dreary it is, how degrading. The boulevard, the children. Three boys running, playing at horses. Seryozha! [her little boy]. And I am losing everything and not getting him back.

(Nabokov 1981, 185)

In this passage, we follow the zigzags of Anna's mind as it roves freely over present impressions and past memories. What William James ––– usually attributed with coining the phrase "stream of consciousness"––– calls the "time-gap" separating past and present consciousness is contracted, with Anna's thoughts bubbling up, as if flooding the floorboards of the mind's "comfortable carriage."

With his nascent modernist stream of consciousness, Tolstoy offers himself as a proto-cinematic writer and, thus, as a sort of advance guard of what will become Nabokov's cinematic assault on the library of poetics. As Ils Huygens reminds us, from its earliest inception, cinema was theorized precisely in terms of its analogy with the human mind. Regarded as a "thought machine," the representational mandate for cinema, for figures such as Jean Epstein, Canudo and Béla ázs, was to visualize the complexity of the mechanism of thought (Huygens 2007). For Alain Resnais, whose Last Year at Marienbad Nabokov evidently admired (Kobel 2001),[3] "the true element of cinema" was thought, precisely because both cinema and thinking succeed in jailbreaking the physical constraints of space, time, and causality. In the "photoplay," as James's friend and associate at Harvard, the psychologist Hugo Munsterberg designated film, "the massive outer world has lost its weight, it has been freed from space, time, and causality, and it has been clothed in the forms of our own consciousness. The mind has triumphed over matter and the pictures roll on with the ease of musical tones."[4]

If one can draw a parallel between the stream of consciousness technique and the cinema, it lies in their joint sabotaging of the linearity through which events routinely unfold in time. While Tolstoy has Anna glide between past and present in his representation of her consciousness, the French new wave filmmakers such as Resnais allow time to fold back on itself. Gilles Deleuze explains that in Resnais' "events do not just succeed each other or simply follow a chronological course; they are constantly being rearranged according to whether they belong to a particular sheet of past, a particular continuum of age, all of which coexist. Did X know A or not? Did Ridder kill Catrine, or was it an accident...?" (Deleuze 1989, 120). One begins to see why Nabokov was so withering in his criticism of the typesetting conceit. To the extent that they mark a turn back to linear narrative models, the italics representing the "cloudburst of thought" would be the typographical symptoms of an "aesthetic relapse."

By this phrase I am referring to Paul de Man's assessment of one's inevitable fall back onto "ideological" models that underpin the system of tropes which, like its own perpetual motion machine, drives forward a certain literary and aesthetic program (de Man 1996). Founded on the master figure of the interiorized consciousness (J.H. Miller 1963) this tropological regime oversees literature's classical models of identity of self and other, of relation, morality and ethical progress and, most powerfully, the poetic conceit of literary redemption and its key promise of an "afterlife" lived through the medium of language. At its base hums the core program, the deus-ex-machina-language of Kantian space and time, whose scarcely perceptible sub-routines were first kick-started by the act of a divine hand. In short, then, the italics setting off the idea of "thought" would signal a fall back into a certain "aesthetic ideology," whose apotheosis is found in the great tradition of romance writing, stretching from Virgil and Tasso to the courtly lovers of the medieval epics, to their reincarnations in Spenser, Sidney and Marvell, and debouching in St Petersburg with Tolstoy's Anna and Vronsky (but not without a late-night supper, as Stepan Oblonsky was so fond of, with the great lovers of the French tradition: Rousseau, Flaubert, Chateaubriand). It is the burden of this creaking, over-painted Arcadian backdrop that Nabokov's italics in Ada are forced to bear ––– no surprise, then, that they teeter on the page aslant.

*

One can now make an initial approach to Ada's garden. A quick review will show that Nabokov (or at least his publisher) does make use of the much-despised italics in Ada. However, they are primarily used to signal the shift into another language, usually French or Russian, sometimes Latin. Italics are also used to typeset Ada's and Van's letters, or to signal an emphasis ("Why should we apollo for her for having experienced a delicious spazmochka?" Ada asks Van on page 338, for example). They are used to indicate book and film titles such as Mlle Larivière's novel, Enfants Maudits and its cinematic adaptation in which Ada and Marina play a minor and starring role, respectively, The Young and the Doomed. Italics also set off citations such as the lines from Chateaubriand's Romance à Hélène that Van and Ada use as a sort of Proustian leitmotif for their love: "Oh! qui me rendra mon Aline/Et le grand chêne et ma colline?" (Nabokov 1996b, 112 and others). And there is a very occasional use of italics to signal an otherwise unmarked shift into a character's consciousness, as a careful combing through of the Library of America edition of Ada will attest.

Each of these instances occurs in chapter five of Part Three, which deals with what the novel's fake blurb ending describes as "one of the highlights of this delightful book" (Nabokov 1996b, 468). By this point, Ada and Van have been apart for seventeen years, a separation that was initiated by Van upon learning of Ada's infidelity with Percy de Prey and Herr Rack (and quite probably numerous others). Ada's half-sister Lucette, who has long been in love with Van, engineers a meeting with him by booking a passage on the same steamer thereby becoming the unwitting vector through which Ada and Van are reunited. Issuing and then following through on her unspoken ultimatum to Van, Lucette jumps from the boat, thereby setting in train Ada's and Van's reconciliation.

Long ago she had made up her mind that by forcing the man whom she absurdly but irrevocably loved to have intercourse with her, even once, she would, somehow, with the help of some prodigious act of nature, transform a brief tactile event into an eternal spiritual tie; but she also knew that if it did not happen on the first night of their voyage, their relationship would slip back into the exhausting, hopeless, hopelessly familiar pattern of banter and counterbanter, with the erotic edge taken for granted, but kept as raw as ever. He understood her condition or at least believed, in despair, that he had understood it, retrospectively, by the time no remedy except Dr. Henry's oil of Atlantic prose could be found in the medicine chest of the past with its banging door and toppling toothbrush. (Nabokov 1996b, 388)

In case the reader missed it, Nabokov, in the shape of a certain anagrammatic "Vivian Darkbloom," helpfully points out in the set of annotations collected at the end of the novel a certain use of italics on this page.[5] The entry for it reads: Henry: Henry James's style is suggested by the italicized "had" (Nabokov 1996b, 483). Pausing for a moment, one should note that while Nabokov was a great admirer of the aforementioned William James and was deeply fond of the psychologist's son and daughter-in-law whom he and Vera befriended in Cambridge, Massachusetts, it was a somewhat more lukewarm affair with the other James. In a letter to Edmund Wilson, he described Henry James a "pale porpoise" whose "plush vulgarities" he urged his friend to "debunk" someday (Nabokov and Wilson 2001, 308). In another letter to Wilson, Nabokov takes exception to an image of a lighted cigar which James describes as having a red tip: "Red tip makes one think of a red pencil or a dog licking itself," he complains. "[It] is quite wrong when applied to the glow of a cigar in pitch-darkness because there is no 'tip'; in fact the glow is blunt. But he thought of a cigar having a tip and then painted the tip red[…]"[6] James, Nabokov concludes, "has charm (as the weak blond prose of Turgenev has), but that's about all" (Nabokov and Wilson 2001, 59). Yet despite these objections, James nonetheless anticipates Nabokov in important ways. One could point to James's own predilection for young overly knowledgeable, prepubescent girls with rhyming names such as Daisy and Maisie as among the literary forerunners of Ada and Lolita. But it is James's enfants maudits from "The Turn of the Screw," Flora and Miles, who more immediately suggest themselves as literary templates for the incestuous children of Ada's 'cinematic' remake.

However, to return to the passage, what "remedy" might "Dr Henry's oil of Atlantic prose" offer in Van's and Lucette's case? How would James's style, that is, locked up in the medicine chest of the past, provide some kind of tincture or salve that could relieve Lucette's "condition"? James is of course the writer of sexual renunciation, the great master of sublimation (and thus very unlike Nabokov in this regard).[7] It is conceivable that, as the narrator weaves in and out of Van's consciousness in this passage (or better, as Van weaves in and out of his present and past consciousnesses), it is this renunciative aspect of James he is referring to as the best treatment for Lucette's unhappy love affair. If she could but sublimate her desire for Van, this would imply, she might have been spared her disaster...

Still, this fails to account for the peculiar temporality introduced by Nabokov's mimicking of Jamesian italics. To follow this, one notes that when James uses italics in his signature manner, it is differently than the way Nabokov decries. If James uses italics to signal the entry into a protagonist's consciousness, it is usually to highlight a moment of self-understanding. In James this is of course frequently also a self-delusion. Thus in The Wings of the Dove, as Densher laps up Aunt Maud's sympathy for his false position as Milly's bereft lover (for, like Van with Lucette, he never really loved Milly at all),[8] he reflects that, after all, albeit in a different way than Maud thinks, "he had been through a mill" (James 1978, 366). So when Nabokov cites James in the passage in Ada, its comic force derives partly from Van's own self-deception and self-justification of his actions.

He understood her condition or at least believed, in despair, that he had understood it, retrospectively, by the time no remedy except Dr. Henry's oil of Atlantic prose could be found in the medicine chest of the past [...]

(Nabokov 1996b, 388).

However, there is also something else going on. Nabokov's sentence turns around the question of Van's understanding, and more particularly of when he understood something, following upon which the tragedy of Lucette's suicide unfolds. The particular difficulty of understanding Van's understanding lies in the italicized word "had." As in the James example, the italicized "had" is the auxiliary of the verb. In both cases, it is used to form the pluperfect tense, which places actions in the past in relation to each other. Recall how English grammar gives us four tenses to indicate an event in the past, the simple past ("I understood"), the past continuous ("I was understanding"), the pluperfect ("I had understood") and the past present continuous (awkwardly in this example, "I had been understanding"). If the simple past merely tells one that an action has been completed, the pluperfect enables one to locate past actions in chronological relation with one another. Thus in the portentous chapter 39, the scene of Van's and Percy de Prey's scuffle on Ada's 16th birthday, we find Van catching a warning expression in Ada's reflected image as they make love over the brook: "Something of the sort had happened somewhere before" (Nabokov 1996b, 213). A straightforward instance of the pluperfect, here the auxiliary verb "had" indicates that while the narrated action is taking place in the past, Van at that moment recalls an event which had taken place earlier than the past event that is the current topic of narration (his and Ada's lovemaking). Things are less clear in the sentence in question, for here the pluperfect is coupled with a time marker from a later time, "he had understood it, retrospectively." It is, moreover, this temporal qualifier "retrospectively" that prevents one from reading the italics simply as extra emphasis, in the sense of "he really had understood"). For with this qualifier, Nabokov describes actions from two different times from the past, first, the simple past: "He understood her condition..." And, second, in the pluperfect: "...he had understood it, retrospectively."

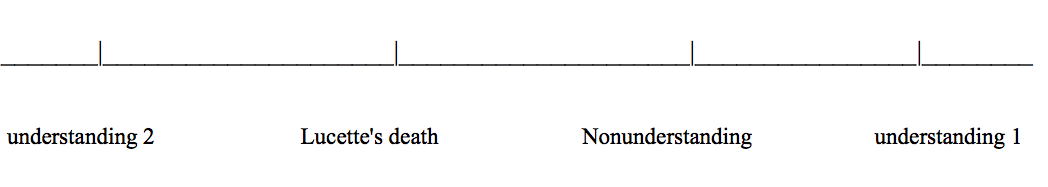

In order to pinpoint exactly where things start to go temporally awry, one can plot the events on a time-line:

Figure 1

The first point on the time-line is the general state of nonunderstanding which takes place in the simple past: before Lucinda's death, Van did not understand her condition. After her suicide, however, Van firstly claims an understanding of her condition (“understanding 1”) but also, second, that he had (already) understood her condition ("understanding 2"). The question is when this second understanding, the one that comes after ("retrospectively") but takes place previously ("had understood") can be temporally located? The use of the pluperfect should suggest it occurs before the first understanding (the simple past). The chronological sequence would then be something like "he had understood", and then, a little redundantly, "he understood" (again).

Figure 2

Plotting this reading in Figure 2, "understanding 2" would have occurred before Lucette's suicide, and thus before it is temporally superseded by "nonunderstanding," which is subsequently overwritten by the simple past of "understanding 1."

However, this is not what Nabokov has written. The sequence Nabokov gives us is: "he understood," "he had understood, retrospectively." Here, an earlier past event would take place after the simple past event. The expected chronology is reversed ––– and indeed, our "understanding" of this sentence recalls nothing so much as the bafflement readers of James frequently feel in trying to follow the flight of the earlier writer's indefinite pronoun as it alights, butterfly-like, first on this fragrantly blooming subject, then on that distant object...

Accordingly, the closest analogue to Nabokov's/James's temporal logic is the ambiguity Jacques Lacan finds in the imperfect verb form in French. In several places in his seminars, Lacan cites an example of the imperfect verb form, "un moment plus tard, la bombe éclatait."[9] In Seminar XV, The Psychoanalytic Act (1967-68), for example, Lacan points to the ambiguity of the imperfect tense where it is impossible to know whether the bomb actually went off (Lacan 1967-68). The implied sense is that the bomb will go off in the very next moment, but the imperfect tense relates it as having taken place in the past. Lacan explains this ambiguity in terms of something from the future that forestalls or "defuses" an event in the past. Illustrating the fundamental disjunction that inheres between the subject and its enjoyment, the imperfect tense depicts how the speaking subject retroactively comes to occupy the place of the id. If Freud's well-known phrase "Wo es war, soll Ich werden" sees the "I" assume the place of the enjoying subject, this is achieved only through a certain sleight of hand. Emerging ex nihilo, the "I" institutes itself as a Law that "retrospectively" ensures that its logic dictates the passage of all that had happened previously.

While Nabokov would no doubt scoff at any suggestion of psychoanalytic insights in his work, in this passage he nonetheless has Van exemplarily accomplish the logical process by which what Lacan calls the thinking (or desiring) subject takes the place of the being of the drive. The thinking or "representing" subject must necessarily be a finite subject, yet to institute this subject requires reaching "back" into a period "before" the subject has an understanding of death and positing this state as taking place "after" ("retrospectively"). According to this paradoxical logic of the finite speaking subject, the same bomb that did go off (éclatait) will not go off (un instant plus tard).

What are the implications of this temporal sleight of hand? Whereas, in the first comprehension, Van understands that Lucette (and he) is finite, in the second comprehension, Van retrospectively "understands" that she (and therefore he) is not finite. Death, which had taken place in the past, becomes revoked by this previous-but-later understanding, which asserts its own "life" in the place death formerly was. Pace Tolstoy's Anna, one can ––– and, in fact, every speaking subject does ––– in this way "tear up the past."

**

Earlier that evening, before her fatal plunge, Lucette and Van are startlingly confronted with Ada's image. Seeking to delay what seems to be their inevitable coupling, Van drags Lucette into the cinema to watch Don Juan's Last Fling in the Tobakoff's on-board cinema. Unexpectedly, the film features Ada who, like her mother Marina, has discovered her vocation as a film actress. If Van has begun to feel the stirrings of desire for Lucette ––– a Technicolor version of her black-and-white "vaginal" half-sister –– once he sees Ada's animated image on the silver screen, all Van's proxy desire for her younger sister flows away.

In the film, Ada, using the screen name Theresa Zegris (anagrammatically, "Haze registers"), has a bit-part as Dolores, "a dancing girl" whose character, the narratorial Van parenthetically notes, was "lifted from Osberg's novella, as was to be proved in the ensuing lawsuit" (Nabokov 1996b,391). As others have noted, Osberg is an anagram of Borges (Rivers and Walker 2014, 271) and the novella referred to is presumably "Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote." In this story, originally published in The Garden of Forking Paths, Borges tells of the attempt by the writer, Pierre Menard, to rewrite Don Quixote. However, this is not to take the form of a revision, nor of a copy nor a mechanical transcription, but rather comprises a version that will absolutely "coincide ––– word for word and line for line" with the words of Cervantes (Borges 1991, 91). For Menard's aim is to write Don Quixote, not as a 20th-century "remake" but to continue "to be Pierre Menard and coming to the Quixote through the experiences of Pierre Menard" (emphasis in original). Not a difficult undertaking, confesses the narrator, except one would need to be "immortal" to carry it out. And sure enough, as he leafs through the 17th-century novel, Borges' editor-narrator analeptically "hears" the voice of the 20th century Menard ringing in Cervantes's "exceptional phrase," "the river nymphs and the dolorous and humid Echo."[10] Borges's "copy" of Cervantes is more 'like' the original than the original itself.[11]

Yet when Nabokov goes to one-up Borges in this shell-game of literary narcissism, it will not be as the voice of a future writer that resounds in the earlier text as in the Borges story but rather Nabokov's own as it piggy-backs down through history on the Cervantes phrase. What is "exceptional" about Cervantes' phrase, "the dolorous and humid Echo," is the way it unconsciously points avant la lettre to Nabokov's Dolores and Hum of Lolita. In this manner, Nabokov is suggesting a different strategy for defeating time. For in a breathtaking gesture of supreme narcissism, Nabokov implies, every text has not only already been written, but all ––– both past and future ––– are plagiarisms of Vladimir Nabokov. Where Borges merely reverses the mimetic logic of original and copy, Nabokov erases it ––– and the spatial and temporal models it implies ––– altogether.

But to return to Ada. In the novel, cinema appears to unseat literature's time-driven narratives of loss and recuperation with an image that can never be lost because it is in the continual present. In the camera's "magic rays," Ada "was again that slip of a girl...." "By some stroke of art, by some enchantment of chance, the few brief scenes she was given formed a perfect compendium of her 1884 and 1888 and 1892 looks" (Nabokov 1996b, 391). Cinema thus offers another "understanding" of death, not as the simple past tense marking life's finitude, nor as its sublimation in "literary" desire, but as the timeless spasm, the sanglot, of an enjoyment without loss.

And again, this other "understanding" of death is expressed in the strange temporality of the pluperfect tense, signaled once again by the telltale Jamesian italics:

Van, however, did not understand until much later (when he saw - had to see; and then see again and again - the entire film, with its melancholy and grotesque ending in Donna Anna's castle) that what seemed an incidental embrace constituted the Stone Cuckold's revenge.

(Nabokov 1996b,392)

But as it turns out, this cinematic "revenge" will hardly be the "remedy" Van seeks. For even if cinema's promise is of a life untouched by time and finitude, death still appears to have had the last laugh in this sequence. The idea of a cinematic enjoyment living on beyond literature's narrative of love lost and time regained will, in truth, be found to be nothing but death as we discover if we return briefly to Tirso de Molina's original stage version of Don Juan, El burlador de Sevilla y convidado de piedra (de Molina 2017).[12] In this 17th century Spanish play by the contemporary of Cervantes, Don Juan, having murdered Don Gonzalo, mocks his victim's corpse in the cemetery. He facetiously invites the Don's statue to dinner only to discover, with shock, his invitation unexpectedly taken up. As the "Stone Guest," Don Gonzalez comes back to life, dining with Don Juan on a meal of vipers and scorpions, before smiting him dead with a thunderbolt.

An initial reading lends the "Stone Guest's revenge" to the simple message of justice having been performed. But a closer look will find his triumph even more far-reaching. In Ada's film version, Don Juan, who has meanwhile started his own watery bleed into that other 17th-century Don, "rides past three windmills, whirling black against an ominous sunset, and saves [Ada-Dolores] from the miller."

Wheezy but still game, Juan carries her across a brook [...]. Now they stand facing each other. She fingers voluptuously the jeweled pommel of his sword, she rubs her firm girl belly against his embroidered tights, and all at once the grimace of a premature spasm writhes across the poor Don's expressive face. He angrily disentangles himself and staggers back to his steed. (Nabokov 1996b, 392)

It turns out that it is not so much the prematurity of the Don's spasm which prevents him from coupling with Dolores that puts us on alert here as the key to death's "revenge." Rather it lies in the way that, taking place in an arche-time "before" the understanding of death, every spasm of enjoyment already constitutes a little death. What Van after repeated viewings of Don Juan's Last Fling finally comes to "understand," in other words, is that jouissance revokes the subject's "life" before it can begin (as a thinking subject). A life founded on enjoyment, such as Eric van Veen ("no relation") envisages with his international enterprise of high-class bordellos, the Villa Venuses, is no life at all (one recalls, too, that Eric was felled, precisely, by a roof-tile's blow to the head, thus repeating his mother's death by flying suitcase that breaks her neck). A thinking subject cannot be co-extensive with enjoyment, it appears. One can either "be" or "think" but neitherat - nor in - the same "time."

Even still, Nabokov will fight with all of his literary powers against this conclusion. One might indeed read his entire aesthetic program as a lifelong assault on this fundamental axiom. Moreover, once one recognizes this, the full extent and meaning of Nabokov's profoundly negative engagement with Freudian psychoanalysis comes properly into view. Beyond his constitutional aversion to its universalizing narratives, his antipathy towards (what he sees as) the crudeness of the psychoanalytic imagination that would herd all singular narratives back towards a single Oedipal origin, Nabokov's real problem with Freud is with his concept of the unconscious. For Nabokov, no "being" is to be found in the unconscious, which contains only the confused and garbled fragments of consciousness. Dreams, claims Nabokov, are merely "amateur" productions: "obviously filched from our waking life, although twisted and combined into new shapes by the experimental producer, who is not necessarily an entertainer from Vienna" (Nabokov 1981, 176). In a famous passage in Speak, Memory, Nabokov lays out his counterclaim to Freud: it is "not in dreams [and, presumably, the other unconscious formations such as slips, jokes and neurotic symptoms] - but when one is wide awake, at moments of robust joy and achievement, on the highest terrace of consciousness, that mortality has a chance to peer beyond its own limits, from the mast, from the past and its castle tower" (Nabokov 1996a, 395-6). For Nabokov consciousness itself suffices. The conscious mind - at least at certain "heights" - must be able to defeat time and death. The question is how?

"from Burning Barn to Burnberry Brook"

If neither literature's desiring narratives of loss and recuperation, nor the cinematic eternal return of jouissance are by themselves powerful enough to overcome the "Stone Cuckold," what if one were to combine them? What if literature and cinema together could comprise a hybrid form that, jamming the core program that runs our perception of space and time, overcomes the limit we perceive as death? What Freud would call the "manifold content" of Ada's incest motif turns out to be Nabokov's cover for infiltrating the traditional categories of space and time with a bastardized literary-cinematic form that will outwit the death underpinning both the literary fantasy and its cinematic other. "Incest" here carries the metaphorical payload of a coupling of brother and sister arts, a cross-bred or, better, inbred form that freezes narrative's temporality with the stasis of the cinematic image that cannot age. In the figures of the two child lovers whose "premature spasms" shock time's forward motion, Nabokov forestalls all coming of the future.

One might ask at this point why it is from Henry James, rather than the other members of the chorus of lovers providing the backing vocals to Ada, that Nabokov obtains his "remedy" against death? What does James uniquely contribute, other than what is offered by Van's and Ada's other accursed precursors, who similarly discovered the secret trapdoor of incest hidden deep in the romance tradition - Byron, Chateaubriand, Sidney, Chateaubriand, Spenser, Coppée, Baudelaire, Mme de Ségur, Rimbaud, Marvell who, among others, make veiled appearances in Ada? The clue will likely be found in James's own tale of enfants maudits that watermarks the whole of Van's and Ada's affair from the beginning, originating with its conduit via Ida Larivière's story-within-a-story, then by way of the film-within-a-story in the form of G.A. Vronsky's movie adaptation of Larivière.

James's famous ghost story, "The Turn of the Screw" (1898) has long posed a problem of interpretation (James 1999). As Edmund Wilson points out in his influential essay, "The Ambiguity of Henry James" (1934), everything in the tale "from beginning to end can be taken equally well in two senses," making it exemplary of the earlier mentioned inherent duplicity of language (Wilson 1962, 170-173). For Wilson, as for a whole slew of James critics after him, the governess is understood as having merely imagined the whole scenario. Her fears of Flora and Miles's corruption at the hands of the dead Peter Quint and Miss Jessel, are merely the hallucinatory fantasies of "the frustrated Anglo-Saxon spinster." The entire story, he maintains, is a "master-piece [...] study in morbid psychology" (Wilson 1962, 172). Thus "The Turn of the Screw," Wilson concludes, is not "about" the children after all but about the governess herself, her misreading the result of her projection of hysterical fantasies onto her small charges. The tale flips Möbius-like around. Its "object" of narration is revealed as the narrating subject.

Thus as it revolves around the hallucinatory question of representation and its real, the story offers a textbook study of the feints and counter-moves - or, as the governess herself describes it, the "succession of flights and drops" - of language's earlier discussed duality. Orbiting in ever-narrowing circles around what she believes to be Flora's and Miles' secret, the governess's narrative finds itself threading dangerously along the narrow divide Foucault alluded to previously: the more she seeks to capture the idea of what her words are to represent, the more she ends up highlighting her narrative's own status as representation. Again, it is largely through James's signature italics that this undecidability of language's subject and object is conveyed. Following an apparent sighting of Miss Jessel, the governess demands of a stubbornly unseeing Mrs. Grose, "You don't see her exactly as we see?"

"[Y]ou mean to say you don't now - now? She's as big as a blazing fire! Only look, dearest woman, look -!"

(James 1999, 429)

Or a little earlier,

"She's there, you little unhappy thing - there, there, there, and you see her as well as you see me!"

(James 1999, 428)

Here, as if by sheer force of will, James's italics seek to pin down an escaping referent. Language's deictic function falters, breaks down from the effort. The promise of indicating a real gets caught in a stutter of repetition that arrests language's forward movement, which buckles under the pressure of Jamesian suspense: "there, there, there." The hint Nabokov will take from James is found in the spark caused by this "jam(m)ing" of the linguistic machine. The "oil" of Dr Henry's prose proves dangerously flammable, susceptible to bursting into "blazing fires." One sees, now, why Nabokov objected so vehemently to James's "painting in" of the cigar's red tip, given the combustion his prose has the powers to ignite, providing perhaps the original spark for the notorious Burning Barn that plays witness to Van's and Ada's first incestuous sexual encounter. The telltale spark shows up again in the note that Blanche leaves for Van, her Franglais warning him of Ada's suspected infidelity, "'One must not berne you.' Only a French-speaking person would use that word for 'dupe'" (Nabokov 1996b, 231). Why should Nabokov post a cross-linguistic pun if not to warn us (and Van) that if words deceive, they also scorch, a lesson that James's little Miles is all too ready to teach his governess: "I kissed his forehead; it was drenched. "So what have you done with [my letter]?" "I've burned it" (James 1999, 446).

It seems that the friction generated by language's "duplicity" as it rubs subjectively and objectively back and forth ignites a flame that is catastrophic for any aesthetic program, and particularly for those founded on the identificatory models through which Nabokov is typically read. It proves especially hazardous for that arch-trope of interiority, the stream of consciousness, unprotected by literature's customary firewalls as it is. Indeed, as Van muses in his own parody of Anna's last day after he receives Blanche's note, "poor Stream of Consciousness, marée noire by now" (Nabokov 1996b, 240). Unencumbered by any "realist" frame to bracket experience into the grammatical categories of past and present, and stripped of the restraining bar of repression, the meandering stream of consciousness surges into an oil spill, a toxic black tide. It takes just a single spark to set it, and the archive that rests upon it, alight...

***

In discussions of Lacan's concept of the sinthome, it is most often James Joyce who is referred to as the exemplary figure. As is well known, for Lacan, Joyce was found capable of stabilizing his latent psychotic structure through his writing (Lacan 2005). Making a sinthome of his name, Joyce succeeds in maintaining the Symbolic, Imaginary and Real in a simulation of the Borromean knot, the rings of which had become loose due to the absence of the paternal signifier. Joyce's ego thus becomes a "corrector" of this relation, enabling the three registers to preserve their respective positions despite floating free from one another: "Through this artifice of writing, I would say that the Borromean knot is restored," Lacan explains (Lacan 2005, 152 my trans.). But as the author of Ada, in his comically narcissistic, grotesquely egotistical masquerade of the Joycean writer, Nabokov is arguably just as exemplary of the writerly sinthome, especially as it pertains to the 21st century.

For many Lacanians, the early part of this century has been notable for the appearance of a new symptomatology–– a marked rise in presentations of anxiety and somatic phenomena that do not easily lend themselves to interpretation. Jacques-Alain Miller has proposed the term "ordinary psychosis" to describe certain cases–– increasingly common it seems–– that do not seem to fit well within the existing psychic structures of neurosis, perversion and psychosis (J-A Miller 2015). In such cases, there appears to be a foreclosure of the paternal signifier, but without the accompanying psychotic features. This leads Miller to return to Lacan's idea of an "untriggered" psychosis, namely, a psychotic structure that is somehow stabilized pre-onset. For "ordinary psychosis," an analytic treatment founded on interpretation is largely ineffective, calling instead for a "post-interpretative" practice (J-A Miller 2007, 8).

An epistemic rather than strictly nosological category, ordinary psychosis comes into view at a moment when the traditional function of the paternal signifier is in decline. The name Miller gives to this historical moment is the "new Real." This "new" - or "worse" - Real now unfolding before our eyes Miller reads as the product of the overarching dominance of the discourses of science and capital over the past hundred years. Miller explains:

It is a question of leaving behind the 20th Century, leaving it behind us in order to renew our practice in a world itself amply restructured by two historical factors, two discourses: the discourse of science and the discourse of capitalism. These are the two prevalent discourses of modernity which, since their respective appearances, have begun to destroy the traditional structure of human experience.

(J-A Miller 2014, 25)

In her own striking approach to today's "new Real," Juliet Flower MacCannell has brilliantly theorized how this retreat of the paternal signifier over the past half-century has precipitated the increasing ascendance of the Imaginary (MacCannell 2016). The picture she paints is recognisable as today's overwhelmingly cinematic culture, the continuous "stream of consciousness" of an enveloping ambient Imaginary. Overturning the limit on enjoyment that the paternal signifier once guaranteed, this new Imaginary–– epitomized by "Trumpism"–– is characterized by a new limitlessness in what may be enjoyed. And as clinicians are discovering, the Lacanian analyst's toolkit of interpretation finds less and less purchase under these conditions. The traditional bracketing effect of the Symbolic, its "realist" conventions of punctuation marking time-gaps is giving way to an all-embracing present suffused by a seemingly unlimited jouissance en toc–– the fakejouissance of the simulated drive satisfactions emerging from our little lathouses, technical i-objects circulating in the "aléthosphère" of the contemporary telepolis, which shower us constantly with pseudo-pleasures.

Into the seamless flows of this strange new screen world, Nabokov, as perhaps the greatest master of Imaginary puppet play that literature has ever known, comes newly into his own, offering himself as advance template for the practice of post-interpretation. Thus in a certain irony he would no doubt have enjoyed, Nabokov - one of psychoanalysis's most bitter and vocal enemies - presages a model for analytic reading in what one might now call the post-Symbolic era. To explain this, recall how the chief difference between neurotic and psychotic structures is that whereas the neurotic's access to enjoyment is mediated by the Name-of-the-Father, whose instituting cut places a prohibition on jouissance, in psychosis, the paternal function is missing. There is accordingly a "hole," as Lacan puts it, in the psychotic's Symbolic system: "At the point at which the Name-of-the-Father is summoned" he explains "a pure and simple hole may thus answer in the Other; due to the lack of metaphoric effect, this hole will give rise to a corresponding hole in the place of phallic signification."[13] It does not take great critical acuity to see how this hole has become the default structure of the new Real, whose other name is climate change or, indeed as Tom Cohen phrases it, "climate panic" (Cohen 2018) It is of a generalized "climate change unconscious" that the new symptomatology of "ordinary psychosis" might be read as a ciphered message. If this message does not lend itself to the traditional practices of reading and interpretation, it is because its content - the incomprehensible idea for us of humanity's extinction –is literally unthinkable through the figures and tropes of the knowledge supported by the master's discourse and the Name-of-the-Father "according to tradition."

In such a case, what remains for analysis and for reading more generally in the 21st century? In the early decades of the 20th century, Joyce created a name from his writing, famously enabling a Real to stream into the Symbolic through his Imaginary ego. As MacCannell explains in her essay, "The Real Imaginary," Joyce constructs his sinthome as a new sort of ego that is open, not closed.

In Joyce, Lacan discovered another kind of imaginary and another kind of ego, an open one: he diagrams the “open ego” as a set of brackets, rather than as a circular link [...] through which experience flows―without being referred back to its effect on the fortress with which it has surrounded itself. This is an ego no longer ensnared in (and buried under) a mass of verbiage that tries to obscure the enormous power of the drives (MacCannell 2008, 56).

If this new ego, in the form of an open bracket could stand in for Joyce's missing paternal signifier in the early part of the twentieth century, that is, at a period when the Name-of-the-Father still performed its traditional function (even if individual fathers such as Joyce's were no longer able to shoulder this role which, as Lacan notes, was always only ever a symptom anyway, Miller 2014, 25), in Nabokov's even more notoriously inflated ego we seem to find something addressed to the proliferating crises of today's "ordinary psychosis."

When Nabokov, through the trope of incest, secretes into the symbolic a jouissance that did not submit to the father's Law, he encrypts this enjoyment into the letters of his name. Nabokov's sinthome –– or cinét-homme–– sees him transform his name into an infinite book that spins out, cinematically, without any of the restraining limits of space, time and history, sucking all past, present and future texts into its "vortex." Not only do the letters VN (and their Russian "reverse" side, BH) link up like a zipper the dual or multiple worlds that critics such as D. Barton Johnson and others have identified as Nabokov's running "theme" (Johnson 1985, Rowe 1981, Alexandrov 2014). As they zigzag across his work, they also stitch into being an impossible world whose contours can never be mapped on a one-to-one basis with any perceptual or narrative space that still pretends to the fiction of a subject and an object. Accordingly, despite the truly heroic efforts of the critical tradition, Nabokov still fails to be read, if by reading one means understanding. To think, Lacan comments, requires one to lean against a signifier but in Nabokov each signifier invariably houses a secret passage, like a fake bookcase in the movies, opening to the homophony of a swarm of letters that pulse incessantly behind it (Lacan 2005, 153). Every potential interpretive "quilting point" - ethics, history, psychology, the spiritual "otherworld" to name only some of the most prominent examples from the Nabokovian critical tradition - invariably trips the in-built wire of Nabokov's electrifying letteration, igniting a fire which burns through the library of critical strategies like an inferno. Or perhaps Lacan's metaphor of a maelstrom is more appropriate this time: "The maelstrom intensifies around the hole, leaving nothing to hold onto, because the edges are the hole itself and because whatever rises up against being drawn into it is precisely its center" (Lacan 2015, 20).[14]

In Ada, or Ardor, Nabokov theorizes this maelstrom as the "lettrocalamity" of a desiring social relation we have (yet to have) understood, retrospectively, as a relation not monumentalized by the paternal cut but rather opening onto the sexual non-rapport precisely by way of what the cut prohibits: incest or the impossible Real enjoyment of lalangue. Nabokov, as cinemathomme, offers himself pre-eminently as a thinker for the "great disorder of the real" implied by the unfolding of human extinction. In Nabokov, the literary perceptual and temporal models of the preceding centuries are forced up against the ultimate "non-thought" - humanity's ecocide - that voids all of the conceptual categories through which humanity's horizons of "life" together with their multifarious literary and cinematic "deaths" have played out up till now. And in the process, as it opens all languages and texts to the vortex of letteral inscription, Nabokov's writing hand also returns the signifier to the first toy it originally was. An infinitely fertile pen, the phallus in Nabokov does not prohibit enjoyment but becomes the playground for a truly "wild" psychoanalysis.

Notes

1. Vladimir Nabokov, Novels 1969-1974: Ada, or Ardor: A Family Chronicle; Transparent Things; Look at the Harlequins! (New York: The Library of America, 1996) 7. Henceforth cited as Ada. ↩

2. Nabokov, "Anna Karenin", Lectures on Russian Literature, ed. Fredson Bowers (Orlando: Harcourt, 1981) 183. Henceforth cited as "Anna Karenin."↩

3. Dimitri Nabokov, cited in Peter Kobel, "Nabokov Won't Be Nailed Down", The New York Times, April 22, 2001 http://www.nytimes.com/2001/04/22/movies/film-nabokov-won-t-be-nailed-down.html?pagewanted=all In his original piece, Jean-Pierre Oudart writes that “suture represents the closure of the cinematic énoncé in line with its relationship with its subject (the filmic subject or rather the cinematic subject), which is recognized, and then put in its place as the spectator” (35). ↩

4. Hugo Munsterberg, The Photoplay: A Psychological Study (New York: Appleton, 1916) 220.↩

5. Titled "Notes to Ada" and similar to the "Commentary notes" Nabokov provides for Anna Karenin at the end of his lecture on Tolstoy, this appendix guides the - frequently confused - reader of Ada through the thicket of allusions in the novel, supplying translations of the French and Russian, proposing definitions for unusual words, and so on. Darkbloom explains, for example, that the novel's opening line is a comic dig at mistranslations of Russian classics, that the novel's transliterations of Russian are based on the old Russian orthography, that the word "granoblastically" means a "in a tesselar (mosaic) jumble", that Tofana is an allusion to "aqua tofana" for whose further meaning we are supposed to consult "any good dictionary" (thus presumably not a detested concise one). ↩

6. The quote continues, "- rather like those false cigarettes - menthol sticks with the end made to look "embery" - that people who try to give up smoking are said to use." Wilson, in reply, urges Nabokov to try The Princess Casamassima and A Small Boy and Others before "giving up" Henry James. (Nabokov and Wilson 211). ↩

7. Nabokov's delight in the comedy of sex is treated by Eric Naiman in his wonderful Nabokov, Perversely (Ithaca: Cornell UP, 2010). ↩

8. Recall that Densher is persuaded by Kate to pretend to make love to the dying Milly so that, with luck, she will leave her fortune to him and thus enable him and Kate to marry. ↩

9. Bruce Fink's translation is "The bomb was to explode a moment later." See Jacques Lacan, "Remarks on Daniel Lagache's Presentation," Écrits, trans., Bruce Fink with Heloise Fink and Russell Grigg (New York: Norton, 1999) 568. Guillaume's original example concerns the derailing of a train but Lacan's substitution of a bomb indicates what is at stake for Lacan, namely, the 'explosion' of jouissance which can only occur in a temporality outside that of the subject's time. For more on the French imperfect and Lacan's use of it, see Alain Merlet, "Imparfait" http://wapol.org/ornicar/articles/219mer.htm. ↩

10. "Las ninfas de los ríos, la dolorosa y húmida Eco." Don Quijote, part 1, ch.26. Centro Virtual Cervantes. https://cvc.cervantes.es/literatura/clasicos/quijote/edicion/parte1/cap26/cap26_02.htm ↩

11. Cervantes himself plays with this idea when, in Part 2, he has Don Quixote encounter a second version of himself who has been roaming the Manchegan plains before him. ↩

12. Tirso de Molina, Three Plays of Tirso de Molina: New Translations of Don Juan: The Jackal of Seville; A Sinner Saved, a Saint Damned; and The Timid Young Man at the Palace Gate, trans. Raymond Conlon (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2017). ↩

13. Lacan, "On a Question Prior to Any Possible Treatment of Psychosis", Écrits: the First Complete Edition in English, trans. Bruce Fink in collaboration with Heloise Fink and Russell Grigg (New York: Norton), 465-6. ↩

14. Lacan, "On a reform in its hole," trans. John Holland, S: Journal of the Circle for Lacanian Ideology Critique 8 (2015): 14-21; 20. ↩

Works Cited

Alexandrov, Vladimir E. Nabokov's Otherworld. Princeton: Princeton UP, 2014. Print.

Borges, Jorge Luis. "Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote," Jorge Luis Borges: Collected Fictions. Trans. Andrew Hurley. London: Penguin, 1999. 88-95. Print.

Cohen, Tom. Ecocide and Inscription 1. London: Open Humanities Press (forthcoming 2018).

Deleuze, Gilles. Cinema 2: The Time-Image. Trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1989. Print.

De Cervantes, Miguel. Don Quixote. Trans. John Ormsby. New York: Norton. 1999. Print.

De Man, Paul. "Kant and Schiller." In Aesthetic Ideology. Ed. Andrzej Warminski. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1996. Print.

De Molina, Tirso. Three Plays of Tirso de Molina: New Translations of Don Juan: The Jackal of Seville; A Sinner Saved, a Saint Damned; and The Timid Young Man at the Palace Gate. Trans. Raymond Conlon. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2017. Print.

Foucault, Michel. The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. New York: Vintage, 1994. Print.

Gregory, Robert. "Porpoise-iveness Without Porpoise: Why Nabokov called James a Fish." The Henry James Review, 6.1 (1984): 52-59. Web. 31 March. 2018.

Huygens, Ils. "Deleuze and Cinema: Moving Images and Movements of Thought." Image and Narrative 18 (2007). Web. 11 March. 2018.

James, Henry. "The Turn of the Screw." In Henry James, Collected Stories, vol. 2. New York: Knopf, 1999. Print.

---, The Wings of the Dove. Ed. J. Donald Crowley and Richard A. Hocks. New York: Norton, 1978. Print.

Johnson, D. Barton. Worlds in Regression: Some Novels of Vladimir Nabokov. Ann Arbor: Ardis, 1985. Print.

Kobel, Peter. "Nabokov Won't Be Nailed Down." The New York Times, April 22, 2001. Web. 11 March 2018.

Lacan, Jacques."Remarks on Daniel Lagache's Presentation." In Écrits. Trans., Bruce Fink with Heloise Fink and Russell Grigg. New York: Norton, 1999. Print.

---, "On a Question Prior to Any Possible Treatment of Psychosis." In Écrits. Trans., Bruce Fink with Heloise Fink and Russell Grigg. New York: Norton, 1999. Print.

---, Le Séminaire, livre XXIII, Le sinthome. Texte établi par Jacques-Alain Miller. Paris: Editions du Seuil, 2005.

---, "On a reform in its hole." Trans. John Holland. S: Journal of the Circle for Lacanian Ideology Critique 8 (2015): 14-21. Web. 11 March. 2018.

---. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book 15, the Psychoanalytic Act (1967-1968). Trans. Cormac Gallagher from unedited French manuscripts. Unpublished.

MacCannell, Juliet Flower. "The Real Imaginary." S: Journal of the Circle for Lacanian Ideology Critique 1 (2008): 46-57. Web. 31 March. 2018.

---, "Refashioning Jouissance for the Age of the Imaginary." Filozofski vestnik, Reason plus Enjoyment. Ed. Kate Montague and Sigi Jöttkandt, 37. 2 (2016): 167-200. Web. 31 March. 2018.

Miller, J. Hillis. ""The Theme of the Disappearance of God in Victorian Poetry." Victorian Studies, 6. 3, Symposium on Victorian Affairs (1963): 207-227. Web. 11 March, 2018.

Miller, Jacques-Alain. "A Real for the 21st Century: Presentation of the 9th WAP Congress." Scilicet, A Real for the 21st Century (2014): 25-35. Print.

---, "Interpretation in Reverse." In The Later Lacan: An Introduction. Ed. Véronique Voruz and Bogdan Wolf. Albany: SUNY Press, 2007. 3-9. Print.

---,"Ordinary psychosis revisited." Lacanian Ink 46 (Fall 2015). Web. 31 March. 2018.

Munsterberg, Hugh. The Photoplay: A Psychological Study. New York: Appleton, 1916. Print.

Nabokov, Vladimir Vladimirovich. "Anna Karenin." In Lectures on Russian Literature. Ed. Fredson Bowers. Orlando: Harcourt, 1981. Print.

---, Vladimir Nabokov, Novels and Memoirs 1941-1951: The Real Life of Sebastian Knight, Bend Sinister, Speak, Memory: An Autobiography Revisited. New York: The Library of America. 1996a. Print.

---, Vladimir Nabokov, Novels 1969-1974: Ada or Ardor: A Family Chronicle; Transparent Things; Look at the Harlequins! New York: The Library of America. 1996b. Print.

---, "Favorite hates." Holograph draft 1964 Oct. Manuscripts and Typescripts. The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, The New York Public Library.

Nabokov, Vladimir Vladimirovich and Edmund Wilson. Dear Bunny, Dear Volodya: The Nabokov - Wilson Letters, 1940-1971. Revised and expanded edition. Ed., annotated and intro by Simon Karlinsky. Berkeley: UCP, 2001. Print.

Naiman, Eric. Nabokov, Perversely. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 2010. Print.

Rivers, J.E. and Charles Nicol Eds. Nabokov's Fifth Arc: Nabokov and Others on His Life's Work. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2014. Print.

Rowe, William Woodin. Nabokov's Spectral Dimension: The Other World of His Works. Ann Arbor: Ardis, 1981. Print.

Wilson, Edmund. "The Ambiguity of Henry James." In The Triple Thinkers: Twelve Essays on Literary Subjects. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1962. 170-173. Print.

Sigi Jöttkandt

Senior Lecturer

University of New South Wales, Australia

s.jottkandt@unsw.edu.au

© Sigi Jöttkandt, 2018